Since my first article on resistant starch (RS) titled Resistant Starch – Friend or Foe?, raw unmodified potato starch, or RUMPS as I like to call it, continues to light up the blogosphere. Like a lot of people, I was caught off guard by the overwhelmingly positive light RUMPS has been cast in. Some people have truly fallen in love with this molecule, or rather two molecules (amylose and amylopectin) all tangled up together. Even Tom Naughton and Mark Sisson have fallen and Jimmy Moore wants to get some. The explosive interest in this topic can be traced to the extraordinary efforts of two flies in the nutritional ointment, Tim Steel, AKA Tatertot and Richard Nikoley of FreeTheAnimal.com.

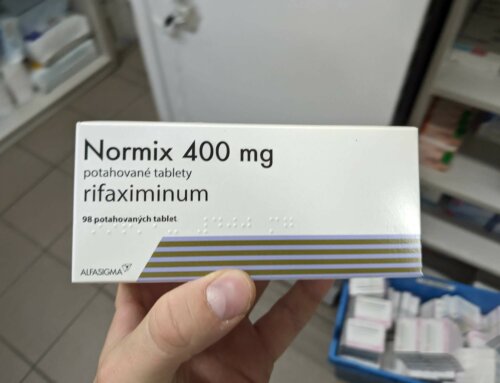

The reported benefits of RUMPS include the enticing claims of better sleep and vivid dreams. Those alone make me want to buy some tonight and give it a try, but there’s more: improved gut function, curing Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth, SIBO (Say what?) preferentially feeding healthy gut bacteria, preventing cancer with more butyrate, immune stimulation, toxin/carcinogen degradation, blood sugar/insulin control, improved cholesterol, triglycerides and even weight-loss.

Most of the claims about RUMPS are unproven, though some are surely real. Some research already supports RS’s effect on blunting postprandial blood sugar spikes, suggesting that RUMPS may be a powerful tool for diabetics and others who suffer from hyperglycemia. But what really caught my attention was the claim that RUMPS will “Cure” SIBO. After all, RUMPS is a form of resistant starch, which I have recommended limiting for SIBO. For more info on this counterintuitive idea, you can visit Dr. BG, AKA Grace, at Animal Pharm and Dr. Art Ayres at Cooling Inflammation. You can also see my mini-debate with Tim in the comments section on Dr. Mike Eades’ blog on heartburn.

Since this idea has been put forward, several people, including some who have experienced side effects with RUMPS, have asked for my opinion on using RUMPS if they have SIBO. Recall my concluding opinion from my first article:

“A state of fermentable substrate limitation in the gut is healthier than a state of fermentable substrate excess and more consistent with Paleo diet concepts (based on limited availability of food, regular fasting while foraging, eating seasonal fruits, etc.). A lean diet for our gut microbes fosters healthy competition in the gut that will favor the survival of well adapted organisms best suited to be our partners in digestion and health. We know that excess malabsorbed carbohydrates (lactose and fructose intolerance for instance) are linked to conditions associated with SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) and there is reason to believe that resistant starch may contribute to imbalances in the gut microbiota including SIBO in susceptible people.”

Since writing this, I have learned a bit more about RUMPS specifically (as opposed to RS in general). I will do my best to provide some thoughts on using RUMPS for SIBO in more or less a pros and cons format. As always, please do add your comments on any points or evidence I may have missed for, or against this approach.

Could RUMPS actually help people with SIBO?

Tim and Richard contacted me recently to discuss some of the experiences people were reporting after supplementing with RUMPS. At that time, we agreed to share all information, both positive and negative about RUMPS and digestive health issues going forward. Realizing that our real goal was to help people and that science will figure this out eventually anyway, we agreed to do our best to speed things up hopefully benefiting all involved. In other words:

“Instead of making science conform to our beliefs, let’s find out what’s real and update our understanding”

And wouldn’t you know it, shortly after making this agreement, I was contacted by someone who had been on antibiotics, had confirmed SIBO and IBS symptoms for years. She had been taking probiotics, eating fermented foods and adding RUMPS to her diet. Other than some bloating and flatulence, she reported feeling better and able to eat a more varied diet without repercussions.

Even though this particular report involves one person who had previously eliminated her symptoms on the Fast Tract Diet (that limits not only RS, but several other fermentable carbs as well), a few other people have also reported improvement in heartburn or other SIBO-related symptoms using RUMPS. To me this suggests there is at least a chance that RUMPS could benefit some people with SIBO. I am open to the idea. Hey, at least we’re talking about diet these days, not PPIs, H2 blockers, gut wrecking antibiotics and some absolutely frightening IBS drugs.

RUMPS is like a “bus” for bacteria:

Pros: One idea proposed to explain why RUMPS might cure SIBO, is that any bacteria overgrowing in the small intestine will adhere to the RUMPS molecules and be whisked back into the large intestine, from whence they came. This is an interesting idea which has some support from a study showing that people infected with Vibrio cholera suffer less fluid loss and recover more quickly when RS is added to the rehydration solution[1]. Supporting this idea is the finding that, under the right conditions, V. cholera can rapidly and efficiently adhere to starch molecules.[2]

Cons/Questions: Some questions remain to determine if these results support using RUMPS with SIBO:

- While bacterial adherence to corn starch was very efficient (98%), adherence to other starch types did not fare as well with very little adherence to wheat starch and no significant adherence to instant potato starch – which admittedly is quite different from RUMPS. RUMPS was not tested for bacterial adherence.

- The adherence testing for the publication was done in the laboratory. No one knows if similar adherence would occur in people’s intestines, though the results agree with the observations in treating Cholera with RS.

- Several other types of bacteria including: L. monocytogenes, S. typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and A. hydrophila, absorbed to the starch much less efficiently (1 – 57% vs. 98% with Cholera). According to the authors, V. cholera can utilize starch for growth while the other bacteria don’t, potentially explaining a purpose behind V. cholera’s ability.

- Sugars utilized by V. cholera including: glucose, maltose, sucrose, trehalose, dextrins, and fructose, blocked adhesion in the lab and could potentially affect binding in vivo (in the small intestine) as well.

- Cholera-induced infectious diarrhea is a dramatic and acute condition caused by a specific pathogen which is quite different from diarrhea-predominant IBS, constipation-predominant or mixed IBS as well as other SIBO-related conditions that involve many different types of bacteria.

Can other resistant starches or fibers accomplish the same thing?

Pros: Another report showed that green banana or pectin fiber improved recovery times of children with diarrhea.[3] In this case, most of children had no specific infectious agent identified, while 40% were diagnosed with either rotavirus (17%), E. coli (11%), V. cholera (5%), or Salmonella (4%).

Cons/questions: The actual amount of resistant starch from green banana is unclear in this study as it was cooked. Also the control diet was rice, but the type or rice and its contribution to the total amount of RS was not determined. Also, in this study, diarrhea had a variety of causes including acute viral and bacterial infections.

Can RUMPS be fermented in the small intestine?

As a rule of thumb, the most rapidly fermentable carbohydrates, if poorly absorbed, have the highest chance of being fermented by bacteria in the small intestine (the home of SIBO for those that have it), where the capacity for excessive fermentation is most limited, and damage most likely to occur. Fructose (grrrrr) and lactose (grrrrr) are good examples of carbs fermented in the small intestine, so it’s no big surprise that they are so well known in the scientific literature as GI trouble makers. But more fermentable forms of fiber such as fructans, pectin, beta glucan and gums are relatively easy to ferment as well. At the other extreme are cellulose, methyl cellulose and lignin that are less fermentable and less of a SIBO threat. Fibers from legumes including stachyose, raffinose and verbascose fall somewhere in the middle along with sugar alcohols.

As with fiber, some forms or RS may be more fermentable than others, with the degree of gelatinization being a factor as well. RUMPS is one type of resistant starch referred to as RS2. You can find a definition of all RS types in my first article. Like the many types of fiber, the various forms of RS have different properties and are fermented at varying rates by different combinations of bacterial species (each species of bacteria have specific abilities in terms of fermenting carbs and often need to work together to get the job done finally consuming the breakdown product (glucose)). Where RUMPS falls in this fermentability continuum is at the heart of the issue in my opinion, and something I admittedly have recently been learning more about

Pros: A study by Olesen, et. al.[4] (thanks for the paper Tim) found that 50 grams of RUMPS (29 g RS), though fermentable, was less fermentable than 10 g of lactulose. Similar results were found in a second study.[5] Lower fermentability translates into fewer symptoms. Lactulose for example, is not digested or absorbed by humans but is highly fermentable by gut bacteria and can cause dramatic GI symptoms including flatulence, bloating, diarrhea, stomach pain, nausea and vomiting. (https://drugs.webmd.boots.com/drugs/drug-259-Lactulose.aspx).

In the Fast Tract Digestion books, I estimate the relative fermentability of fiber types. Perhaps RUMPS should be reclassified as a fiber and belongs on the lower end of that list, say above cellulose but below pectin, raffinose, stachyose and verbascose and may be less symptom provoking than more fermentable carbs.

Cons/questions: Though I don’t know the glycemic index of RUMPS specifically, the GI of another type II resistant starch, Hylon VII corn starch is 50, indicating that half of the starch is broken down and absorbed in the small intestine.[6] If human starch degrading enzymes are able to breakdown resistant starch, why wouldn’t bacteria that possess starch-degrading enzymes, known to be present in SIBO, do the same. Of course the question here is how different is RUMPS from Hylon VII.

RUMPS and LIBO?

It’s tempting to assume that if RUMPS is not fermented in the small intestine, it won’t trigger any SIBO-like symptoms. But there is the question of excessive fermentation in the large intestine. Before SIBO, excessive bacterial fermentation was referred to as dysbiosis, or a general imbalance or overgrowth of intestinal microbiota believed to be associated with bowel inflammation. Though not typically specified, dysbiosis can include bacterial overgrowth growth in the large intestine. You could think of this as LIBO for Large Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Is it possible LIBO could also contribute to symptoms more commonly attributed to SIBO? Since our large intestine is designed to support more extensive fermentation, it’s easy to assume “the more fermentation the better” as long as it’s in the large intestine, but I am not so sure. Since SIBO is associated with bacteria originating from the large intestine, is it possible that LIBO can give rise to SIBO?

Years ago, I suffered chronically with acid reflux (before reducing fermentable carbs in my own diet). I often noticed occasional bouts of acid reflux some 12-24 hours after consuming foods with a high fermentation potential (hard to digest carbs). Though research on this phenomenon is lacking, I wonder if excessive fermentation in the large intestine could contribute to acid reflux, IBS and other symptoms more commonly associated with SIBO. If this were the case, even slower to metabolize fibers and RS could trigger symptoms.

Pros: The idea that RUMPS could cause symptoms via LIBO is speculative.

Cons: If correct, RUMPS could trigger symptoms via excessive fermentation in the large intestine

RUMPS GI Side Effects

I still remember the parties we had in high school. Get a hold of some beer. Invite your friends and their friends over and put on some Jimmy Hendrix (yes, it was the 70s). Early on everyone is focused on the fun and excitement, but then you realize its 2:00 AM, Bobby dropped some acid and is typing something on your mom’s typewriter, the foreign exchange student is vomiting in the bedroom and your sister’s boyfriend just tore up the front lawn with his Camaro and is now stuck dangling over the embankment (true story). At some point, common sense kicks in and it’s time to wind the party down a notch and take stock.

I think this is what’s happening with RUMPS. It’s tempting to throw caution to the wind when you’re chasing amazing health claims. But I have been surprised to see many comments from people suffering with side effects of RUMPS who continue to use the supplement, even upping the dosage in some cases. Before we resume the RUMPS party, let’s take a look at people reporting side effects on RUMPS.

In my first post on RS, I discussed the “bread and muffin study” showing that these RS-containing foods invoked more symptoms in people with IBS, I noted that 80 % of cystic fibrosis patients, who are often deficient for the release of starch degrading amylase enzyme and test positive for SIBO, suffer from acid reflux (Refer to Fast Tract Digestion Heartburn for the evidence tying acid reflux to SIBO). I also talked about the similarity between the symptoms of SIBO and the side effects of drugs and supplements that block starch digestion.

Consistent with these observations, reports of GI side effects from RS (not RUMPS specifically) include: flatulence, bloating, stomach aches, cramps and diarrhea.[7],[8] Though both studies were conducted in healthy people, the reported side effects are consistent with SIBO or a general imbalance of gut microbes – dysbiosis. I would expect the side effects to be worse, not better, in people who already had established SIBO or dysbiosis.

While most people supplementing with RUMPS report varying amounts of flatulence, some report additional side effects including: abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, gas, bloating, acid reflux, nausea, cramps fatigue, and even intestinal blockage. These reports come from the comment sections under the many RUMPS blogs. Keep in mind they are anecdotal (n=1) reports so we shouldn’t read too much into them, but we also can’t ignore them.

These reports of side effects mirror my own experiences over the years with RS in general. Though I don’t supplement with RUMPS, I suffer from acid reflux when I consume pasta or certain rices and breads with high levels of RS. My gut can tell the difference between basmati rice (high RS) and jasmine rice (no RS) with a fairly high degree of certainty.

Tim Steele recounted to me his own experience when he consumed additional RUMPS in response to a bout of indigestion. These are his words: “I felt some indigestion coming on, and took 4TBS of RUMPS in a glass of water. Almost instantly, the heartburn was unbearable, nearly doubled me over. I ate at least 6 TUMS and got a bit of relief, but the discomfort actually lasted all night and into the next day.”

Richard Nikoley also recounted to me a report of someone having to stop supplementing with RUMPS: “because after a while it gave him perpetual heartburn for days.”

A post from Mark’s Daily Apple recently stated: “A note for those experiencing heartburn from the PS, it has taken over a week off the PS to get the HB under control.”

A post on Facebook, though not specifically about RUMPS, noted: “Several of us in The Paleo Approach Group have problems digesting plantains. I had issues for over a week, severe stomach pain and psychological issues, worse than anything I’ve eaten in a long time. I’m thinking it has to do with the large amount of resistant starch feeding bad bacteria.”

RUMPS AI Side Effects

Others have complained that RUMPS exacerbated their preexisting autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Symptoms included joint pain in the hip, knee, extremities and back. Despite the side effects, some people continue to supplement hoping to gain benefit even though their own bodies are telling them to stop. Before assuming that RUMPS is the appropriate course of action for AI conditions, a thorough review (beyond this article) of bacterial involvement in specific AI conditions is in order. For instance:

- K. pneumonia (capable or degrading RS) overgrowth and antibodies to the same have been linked to AS and possibly Crohn’s disease, and dietary starch restriction has been proposed as a treatment strategy[9].

- RA has been linked to increased intestinal populations of Prevotella copri and a decrease in Bacteroides strains,[10] Yet Prevotella is associated with carbohydrate-based diets while Bacteroides is associated with animal-based diets.[11]

Note: RA has also been linked to urinary tract infections caused by the bacterium Proteus mirabilis.[12] How these two very different bacterial strains, one growing in the gut (Prevotella. copri) and one causing UTI infections (Proteus mirabilis), contribute to RA has yet to be determined.

Given the complexity of AI and SIBO-related conditions, can we assume (as has been commonly stated) that people with these conditions will always benefit by improving their “good” and reducing their “bad” gut microbes with RUMPS? In reality this strategy has not been proven and does not seem to be working, at least for some people who may be ignoring the risks in pursuit of perceived benefit. I remain open, but continue to believe that RUMPS has the potential to invoke symptoms in people who have SIBO or are susceptible to SIBO or dysbiosis, particularly if they consume higher doses.

The connection between gut microbiota, SIBO and diet

We know that our gut microbiota can be significantly influenced by diet and disease. But understanding what this means will take some time. Studies show that people with IBS (IBS is definitively linked to SIBO) have increases in Firmicutes type bacteria Dorea, Ruminococcus, and Clostridium spp., and decreases in Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria (Bifidobacterium), and one specific Firmicutes –Faecalibacterium spp.[13],[14] A study by Malinen and colleagues,[15] found that a predominance of Ruminococcus type bacteria (related to R. torques) was associated with severity of bowel symptoms in IBS subjects. However, within this high group, several species of Clostridia were significantly reduced. A study looking at microbiota changes in IBSD and IBSC found that R. torques was more prevalent in IBS-D and R. bromii (recall the “keystone species” in RS fermentation) was associated with IBS-C patients in comparison to control subjects.[16] Another study showed that the microbiota in IBS-D patients was enriched in Proteobacteria and Firmicutes (particularly Lachnospiraceae and sometimes R. torques), but reduced in Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes compared to controls.[17]

Table 1. Microbiota characteristics and population changes in IBS

| Microbiota type | Relative change in IBS | Gas producing | Starch degrading |

| Firmicutes | Increased |

+ |

++ |

|

Increased |

+ |

++ |

|

Increased |

+ |

++ |

|

Increased |

+ |

++ |

|

Unknown |

+ |

++ |

|

No change |

+ |

++ |

|

Increased or decreased |

+ |

+ |

|

Increased |

+ |

+ |

|

Increased |

+ |

+ |

|

Decreased |

– |

+ |

| Proteobacteria | No change or increased |

+/- |

– |

| Actinobacteria (bifidobacterium)[13] | Decreased |

– |

+/- |

| Bacteroides[20],[21] | Decreased |

+/- |

+/- |

While there are many contributing factors for SIBO and IBS covered in Fast Tract Digestion IBS that may alter microbiota composition, and different studies yielded some variability in results, the microbiota profiles of people with IBS show an important trend. Two things struck me immediately after putting the data into a table:

- IBS involves increases in many Firmicutes type bacteria, which are most adept at degrading polysaccharides such as resistant starch, and a decrease in more nutritionally versatile Bacteroidetes and certain Clostridia. Actinobacteria were also lower in IBS.

- The Firmicutes type bacteria that are increased, are most proficient at producing (mostly hydrogen and carbon dioxide) gas.

The connection between IBS and increases in bacterial species that preferentially ferment complex carbs and produce gas is consistent with the success of diets that limit fermentable carbs for IBS, acid reflux and other SIBO related conditions – covered in my first article.

Irritable Bowle Syndron (IBS) and Obesity

The microbiota profile of people with IBS is consistent with a diet rich in fermentable carbs. The same is true for obese individuals, which may explain the connection between obesity and GI symptoms including bloating, diarrhea, and an even stronger connection with acid reflux.[22],[23]

In a study of overweight men, a diet supplemented with RS yielded significant increases in Ruminococcaeae, Roseburia and E. rectale, which decreased significantly when subjects were switched to a lower carb weight-loss diet.[24] Similar results were obtained in study on the effects of reducing dietary carbohydrates (high carb 399g/day, moderate carb 164g/day, low carb 24g/day) on microbiota in obese men.[25] As dietary carbs were lowered, the researchers observed a decrease in Roseburia and E. rectale related (clostridial cluster XIVa) species as well as bifidobacteria (Actinobacteria). Bacteriodes group and Clostridium coccoides group bacteria as well as clostridial cluster IX group bacteria were not significantly affected by reducing dietary carbs.

In general, obesity is associated with a significant decrease in microbiota diversity with fewer Bacteroidetes (associated with more diversity) and more Firmicutes and Actinobacteria (associated with less diversity).[26] The authors found that the obese human gut microbiome (microbiome refers to gut microbe genes, whereas microbiota refers to the actual bacteria) is genetically enriched for phosphotransferase systems involved in microbial processing of carbohydrates. They likened the obese gut microbiota more to fertilizer runoff, where abnormal energy input creates blooms of less diverse microorganisms, compared to a lean gut microbiota that is actually more like a rain forest. These findings are in agreement with other microbiota studies on obesity.[27],[28],[29],[30] The reason may have to do with the ability of Bacteroidetes type bacteria, as well as some Clostridia species, to use a variety of both animal and plant based nutrients making them less dependent on complex carbohydrates.

Note: Two notable differences between obesity and IBS: Both Actinobacteria and E. rectale levels were observed to be increased in obesity but decreased or unchanged respectively in IBS.

What is the best diet for SIBO and obesity?

RUMPS is believed to promote the growth of “good bacteria” and increase gut microbiota diversity. This intuitively makes some sense as RUMPS and other complex fermentable carbs feed or cross-feed many types of bacteria in the gut, most of which reside in the large intestine. RUMPS would therefore be expected to increase the numbers and possibly the diversity of organisms that can participate in carbohydrate breakdown.

But the studies cited above indicate that complex polysaccharides result in more Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and certain Clostridia but less diversity overall due to a decrease in Bacteroidetes and several other Clostridia species. Similar changes are associated with the symptoms of IBS.

The diet that continues to make the most sense for people with SIBO (and obesity?) in my view, is one that limits (not eliminates) fermentable carbs putting the polysaccharide loving microbes on a diet so to speak. Animal-based foods in combination with moderate / reduced levels of fermentable carbs promote bacterial species that metabolize amino acids and other animal-based macronutrients as well as a moderate level of Firmicutes and Clostridia that prefer complex carbs.

Even Dr BG from Animal Pharm says “For SIBO and intestinal permeability, it’s actually healing to minimize fermentation if it is occurring pathologically in the small intestines… where it shouldn’t be.”

How many complex carbs is the right amount?

The best mix of complex carbs to animal-based proteins and fats will depend on the age, health, and gut microbiota makeup of each individual. There are three basic types of diet in terms of fermentable carb levels. At one end is the elemental diet which provides zero fermentable carbs. In the middle are moderate fermentable carb diets which include: low starch, low carb, low FODMAP, and my own Fast Tract Diet. At the other extreme are diets that contain an excess of fermentable carbohydrates including the Standard American Diet (SAD), Vegetarian diets and diets that include fermentable carb supplements such as inulin, fructose oligosaccharide, fiber or RUMPS.

Diets with no fermentable carbs

While elemental diets (predigested carbohydrates, proteins and fats) are very effective at normalizing SIBO symptoms in IBS,[31] going too low on fermentable carbs may not be a great long term strategy. People who are very ill with conditions such as active Crohn’s disease can benefit dramatically (supporting remission) from the elemental diet, however eliminating all fermentable carbohydrates does decrease microbiota diversity which may have negative consequences long term.

One example is the connection between enteral tube feeding with the elemental diet and C. diff infection.[32] The risk of C diff. may be from the diet reducing protective bacteria or their metabolic end products, but there are many other risk factors that may also be responsible including: People in the study were very sick to begin with and often hospitalized where C diff infections are commonly acquired. Patients were often on antibiotics or PPI drugs which both increase the changes of C diff. Also, tube feeding increases the chances of C diff exposure. Regardless, common sense indicates that including some level of fermentable carbs in the diet is the healthy thing to do. In addition to a variety of health benefits from a robust microbiota, we get up to 20 – 25% of our calories from the fats that gut bacteria make.

Diets with high levels of fermentable carbs

High fermentable carb diets include vegan, Standard Amer. Diet or SAD, and diets supplemented with high fiber, prebiotics or RS. Feeding our gut microbes with plenty of fermentable carbs on the surface sounds like a great idea. But we can see that Firmicutes and certain Clostridia bacteria may take advantage of this high fermentation burden in people susceptible to bacterial overgrowth. It’s easy to ignore the many other sources of fermentable material gut bacteria have available including: Unabsorbed proteins, mucus, nucleic acids and other macromolecules.

To make matters worse, people with SIBO often have malabsorption issues – it’s a double whammy. Carbohydrate malabsorption theoretically makes the effective GI of carb-containing foods lower. Therefore people with SIBO likely end up with more fermentable carbs in their intestines after the same meal compared to people that don’t suffer from malabsorption. Also, people with IBS may have an additional source of fermentable carbs, mucin. IBS patients overexpress the gene for mucin production, Muc20.[33] Mucin is a fermentable substrate. Top mucin degraders include Rumminococcus, particularly R. torques, but also bifidobacteria.

Since most people already agree with the monumental problems with the SAD diet, I won’t comment further and limit the discussion to diets that have lots of resistant starch or add RUMPS or other fermentable carb supplements. I have no issue with young healthy people, or older healthy people for that matter, consuming lots of fermentable carbs and there is even some evidence that RS may help with infectious diarrhea. If you’re supplementing with RUMPS and suffering no negative consequences, you have my blessing by all means. But as you have seen in the side effects section, not everyone escapes the negative consequences of excessive fermentation if they include too many fermentable carbs.

Diets moderate in fermentable carbs

Microbiologists estimate that our gut microbes ferment approximately 60-80 grams of fermentable carbs per day to account for one typical day of fecal output accounting for metabolic loss.[34] But how many fermentable carbs are in our diet? To answer this, I developed a formula called Fermentation Potential (see more information in the Fast Tract Digestion books).

Using this formula, I have estimated that typical Western diets actually contain well over 100 grams / day of fermentable carbs. As little as 30 grams of carbs allow gas-forming gut bacteria to produce 10 liters of hydrogen gas. Also, recall the many sources of fermentable material listed above which are available to gut bacteria. Several moderate fermentable carb diets mentioned above reduce the fermentative burden and improve symptoms of SIBO-related conditions. For a review of these diets along with the elemental diet, check out this article on SIBO Diets.

Because I don’t think these other diets go far enough, I created the Fast Tract Diet, and FP system. My goal was to quantitatively reduce hard to digest fermentable carbs to 45 grams per day or less to “quite the gut” so to speak and allow the body’s control mechanisms including motility, acidity and immune system to clean house reducing the overall number of microorganisms to restore some order from chaos.

Concluding Remarks

We have been endowed through evolution with a huge variety of helpful gut microbes that perform a variety of important functions supporting our health and nutrition. We are just beginning to understand specific growth patterns of gut bacteria in response to diet, particularly fermentable carbs. These patterns will likely be different for different people, especially people who are obese or suffer from SIBO-related conditions. Developing an extensive image of gut bacterial types (phylum/enterotype, genus and species) able to participate in the breakdown of various fermentable carbs and their connection with digestive and autoimmune diseases as well as obesity will help.

While keeping an open mind to the benefits of RUMPS, my own view still leans towards the concept that RUMPS, though potentially less threatening, belongs in the group of hard-to-digest but fermentable carbs, which also include: lactose (for lactose-intolerant), fructose, other forms of RS, fiber and sugar alcohols. I believe limiting all five types is key to getting control of symptoms of IBS, acid reflux and other SIBO-related conditions. But there needs to be balance. I don’t think diets that eliminate fermentable carbs or diets with excessive amounts of fermentable carbs are healthy diet for people with SIBO. I recommend some skepticism concerning RUMPS for people with SIBO or autoimmune-related conditions based on the following:

- Reported GI side effects from many supplementing with RUMPS that are constant with the GI side effect of RS published in the scientific literature.

- Anecdotal reports of autoimmune side effects with RUMPS.

- Early research on gut bacterial enterotypes suggests that overgrowing, carb-loving, gas producing bacteria may be a factor in IBS and obesity.

- Complex polysaccharides including RS may be reducing, not increasing, the diversity of our gut microbes, feeding blooms of gas-producing bacteria and driving symptoms.

But I don’t want to completely close the door on using RUMPS for treating SIBO for a number of reasons:

- A few people with SIBO, IBS or acid reflux have reported improvement supplementing with RUMPs – I can’t argue with that if it works. Given the complexity of SIBO and dysbiosis, there may be certain individuals with SIBO who may benefit from RUMPS.

- There is a plausible mechanism, particularly in the case of diarrhea-predominant IBS – RS is like a bus.

- The low relative fermentability of RUMPS suggests it may be less symptom-provoking than other fermentable carbs (I learned something new).

- Careful dosing (reductions) for people with SIBO has not been tried / studied and could provide benefits with fewer side effects.

Of course only time and actual studies in people with SIBO-related conditions will tell us for sure if RUMPS is therapeutic for treating SIBO.

General recommendations

People with SIBO-related conditions suffer from a variety of underlying issues including: intestinal scarring, motility problems, gastroenteritis (infection or food poisoning), malabsorption due to intestinal villi, (needed for absorbing nutrients) damage, digestive enzyme deficiency, immune deficiency, low stomach acid, antibiotic use, or even genetic susceptibility based on Crohn’s, Celiac or other autoimmune conditions.

If you have signs or symptoms of SIBO or dysbiosis, I recommend the following:

- Reduce excessive gut fermentation by adopting the Fast Tract Diet that quantitatively limits all difficult-to-digest fermentable carbs.

- Work with your own health practitioner to explore, and where possible correct, potential underlying causes of SIBO listed above.

- Once you reach a baseline where excessive inflammation, SIBO and symptoms are under control, you can begin to experiment with gradually adding back more fermentable carbs including RUMPS (start with ½ teaspoon with lots of water) and see how it goes.

- Your gut microbiota can recover over time provided you don’t overfeed it, avoid antibiotics and address any underlying issues identified in step 2. You can experiment with adding probiotics (lactic acid, bifidobacteria or even soil-based probiotics), but to date, probiotics have not been shown to be very effective for IBS (the exception being some possible benefit for diarrhea) likely because most don’t become established in the gut. The gut is a highly specialized ecosystem in which bacteria have actually evolved the tools to colonize it. Though some probiotics might remain transiently and a few may even become established, rebuilding your microbiota occurs gradually overtime with fecal-oral transfer from house mates likely being one of the most significant sources of gut bacteria that can become established.

Notes:

- Hard-to-digest “fermentable carbs” are quite different from “fermented carbs”. Fermented carbs have already been fermented outside the body in an incubator- think yogurt. Fermented carbs are mostly used up and replaced with short chain fatty acids. Fermented foods (unsweetened) are low carb / low fermentation potential and are safe to eat and encouraged on the Fast Tract Diet.

- You can always have your own microbiota tested to see what’s going on.

- The next wave of understanding will likely come when we understand how microbiota changes in luminal or unattached bacterial enterotypes relate or not to changes in mucosal or attached bacterial enterotypes in digestive health and illness.

- The Fast Tract Digestion books have a whole chapter on identifying and addressing the many underlying causes of SIBO.

References

[1] Ramakrishna BS1, Venkataraman S, Srinivasan P, Dash P, Young GP, Binder HJ. Amylase-resistant starch plus oral rehydration solution for cholera. N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 3;342(5):308-13.

[2] Gancz H1, Niderman-Meyer O, Broza M, Kashi Y, Shimoni E. Adhesion of Vibrio cholerae to granular starches. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005 Aug;71(8):4850-5.

[3] Rabbani GH1, Teka T, Zaman B, Majid N, Khatun M, Fuchs GJ. Clinical studies in persistent diarrhea: dietary management with green banana or pectin in Bangladeshi children. Gastroenterology. 2001 Sep;121(3):554-60.

[4] Olesen M1, Rumessen JJ, Gudmand-Høyer E. Intestinal transport and fermentation of resistant starch evaluated by the hydrogen breath test. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994 Oct;48(10):692-701.

[5] Heijnen ML1, Deurenberg P, van Amelsvoort JM, Beynen AC. Replacement of digestible by resistant starch lowers diet-induced thermogenesis in healthy men. Br J Nutr. 1995 Mar;73(3):423-32.

[6] Vonk RJ1, Hagedoorn RE, de Graaff R, Elzinga H, Tabak S, Yang YX, Stellaard F.Digestion of so-called resistant starch sources in the human small intestine. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Aug;72(2):432-8.

[7] Heijnen ML, van Amelsvoort JM, Deurenberg P, Beynen AC.Neither raw nor retrograded resistant starch lowers fasting serum cholesterol concentrations in healthy normolipidemic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 Sep;64(3):312-8.

[8] Muir JG1, Lu ZX, Young GP, Cameron-Smith D, Collier GR, O’Dea K Resistant starch in the diet increases breath hydrogen and serum acetate in human subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995 Apr;61(4):792-9.

[9] Rashid T1, Wilson C, Ebringer A. The link between ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, Klebsiella, and starch consumption. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:872632.

[10] Scher JU1, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, Segata N, et.al. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. Elife. 2013 Nov 5;2:e01202.

[11] Wu GD1, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, et.al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011 Oct 7;334(6052):105-8.

[12] Ebringer A1, Rashid T. Rheumatoid arthritis is caused by a Proteus urinary tract infection. APMIS. 2013 Aug 29. doi: 10.1111/apm.12154.

[13] Rajilić-Stojanović M1, Biagi E, Heilig HG, Kajander K, Kekkonen RA, Tims S, de Vos WM. Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011 Nov;141(5):1792-801.

[14] Jeffery IB1, O’Toole PW, Öhman L, Claesson MJ, Deane J, Quigley EM, Simrén M. An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut. 2012 Jul;61(7):997-1006.

[15] Malinen E1, Krogius-Kurikka L, Lyra A, Nikkilä J. et.al. Association of symptoms with gastrointestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep 28;16(36):4532-40.

[16] Lyra A1, Rinttilä T, Nikkilä J, Krogius-Kurikka L, Kajander K, Malinen E, Mättö J, Mäkelä L, Palva A. Diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome distinguishable by 16S rRNA gene phylotype quantification. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Dec 21;15(47):5936-45.

[17] Krogius-Kurikka L, Lyra A, Malinen E, Aarnikunnas J, et.al. Microbial community analysis reveals high level phylogenetic alterations in the overall gastrointestinal microbiota of diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome sufferers. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009 Dec 17;9:95.

[18] McKay LF, Holbrook WP, Eastwood MA. Methane and hydrogen production by human intestinal anaerobic bacteria. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand B. 1982 Jun;90(3):257-60.

[19] Walker AW1, Ince J, Duncan SH, Webster LM, et.al. Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. ISME J. 2011 Feb;5(2):220-30.

[20] McKay LF, Holbrook WP, Eastwood MA. Methane and hydrogen production by human intestinal anaerobic bacteria. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand B. 1982 Jun;90(3):257-60.

[21] Walker AW1, Ince J, Duncan SH, Webster LM, et.al. Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. ISME J. 2011 Feb;5(2):220-30.

[22] Delgado-Aros S1, Locke GR 3rd, Camilleri M, Talley NJ, Fett S, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Obesity is associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal symptoms: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Sep;99(9):1801-6.

[23] Hagen J, Deitel M, Khanna RK, Ilves R. Gastroesophageal reflux in the massively obese. Int. Surg. 1987 Jan-Mar;72(1):1-3. Fisher BL, Pennathur A, Mutnick JL, Little AG. Obesity correlates with gastroesophageal reflux. Dig Dis Sci. 1999 Nov;44(11):2290-4. Austin GL, Thiny MT, Westman EC, Yancy WS Jr, Shaheen NJ. A very low-carbohydrate diet improves gastroesophageal reflux and its symptoms (Obese patients). Dig Dis Sci. 2006 Aug;51(8):1307-12.

[24] Walker AW1, Ince J, Duncan SH, Webster LM, et.al. Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. ISME J. 2011 Feb;5(2):220-30.

[25] Duncan SH, Belenguer A, Holtrop G, Johnstone AM, Flint HJ, Lobley GE. Reduced dietary intake of carbohydrates by obese subjects results in decreased concentrations of butyrate and butyrate-producing bacteria in feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007 Feb;73(4):1073-8.

[26] Turnbaugh PJ1, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, Egholm M, Henrissat B, Heath AC, Knight R, Gordon JI. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009 Jan 22;457(7228):480-4.

[27] Ley RE1, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006 Dec 21;444(7122):1022-3.

[28] Turnbaugh PJ1, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006 Dec 21;444(7122):1027-31.

[29] Turnbaugh PJ1, Bäckhed F, Fulton L, Gordon JI. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2008 Apr 17;3(4):213-23.

[30] Schwiertz A, Taras D, Schäfer K, Beijer S, Bos NA, Donus C, Hardt PD. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010 Jan;18(1):190-5.

[31] Pimentel M1, Constantino T, Kong Y, Bajwa M, Rezaei A, Park S A 14-day elemental diet is highly effective in normalizing the lactulose breath test. Dig Dis Sci. 2004 Jan;49(1):73-7.

[32] O’Keefe SJ. Tube feeding, the microbiota, and Clostridium difficile infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jan 14;16(2):139-42.

[33] Aerssens J, Camilleri M, Talloen W, Thielemans L, et.al. Alterations in mucosal immunity identified in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Feb;6(2):194-205.

[34] Topping DL1, Clifton PM.Short-chain fatty acids and human colonic function: roles of resistant starch and nonstarch polysaccharides. Physiol Rev. 2001 Jul;81(3):1031-64.

How fitting, I get to be first!

Thank you so much for the in-depth look, this will be a very valuable article for a long time and hopefully assist many people in making wise decisions.

As I relayed, RUMPS on an inflamed, dyspeptic stomach is not comforting in the least! My dyspepsia seemingly caused by a slight overdose of ibuprofen. If this were a chronic condition and not just temporary as in my case that night, I feel for anyone who has it.

So many different problems associated with digestion. RUMPS has actually turned into somewhat of a litmus test for broken guts. Instant discomfort would seem to indicate a problem in the stomach. Discomfort from 30-60ish minutes after would be in the small intestine, and discomfort after 3-4+ hours would be an issue with large intestine.

It seems the average Joe with no history of digestive troubles is generally able to digest 3-4TBS with no problems, but still may end up with a bit more flatulence that he likes. In this case, the “Soil-based organisms” seem to help most as they are the primary and secondary degraders of the RS. The end result being a boost in butyrate production and thriving colonies of bifidobacteria that stay put and do what they are supposed to do.

But, digestive issues aside, this has been quite a learning experience for all of us and it has been great exchanging ideas with you, Norm. Everyone deserves the best gut possible for quality of life, and anything that gets people off PPIs and antibiotics is great in my book.

Tim

Hey Tim, Thanks for your perspective. Yes, it has been, and continues to be, quite a learning experience indeed.

Hey Norm, thanks so much for the thoughtful post. I’m particularly interested in your thoughts (and all others willing to weigh in!) regarding AS, klebsiella, and their relation to RS.

I’m HLA-B27+, with psoriatic arthritis that includes spinal involvement. In addition I tested positive for high amounts (“potentially pathogenic”) amounts of klebsiella pneumoniae on a Genova stool test. Given this, I consider it to be a pretty close relative to AS.

Now I’ve been on a no starch, no sugar, no refined carbs diet for going on a year now. I’ve had slight symptom reduction (I also started LDN during the year), but not the success I’m looking for (or that other people have reported). I personally started the protocol Art Ayers is recommending (RS + probiotic cocktail) a couple days ago.

So personal history aside, the meat of my question is: if we look at Tim’s n=1 American Gut data https://freetheanimal.com/2013/11/resistant-american-comparison.html we see his proteobacteria band is considerably smaller than average. Am I right that klebsiella is a Gammaproteobacteria which would fall under the proteobacteria band?

If we pretend that Tim’s results are standard and not just an n=1, wouldn’t this be evidence of RS helping other bacteria overtake the klebsiella? And then assuming the link between the AS and kp is causative, that it might help the condition?

Thanks again for the incredibly well researched post!

Cooper

Hi Cooper,

Thanks for the post and a really great question. At the macro level, having less Proteobacteria would seem to be a good thing if you were worried about being colonized with one of it’s members (Kleb), but I think the micro level is much more important in your case. Bacteria within a given enterotype often have very different metabolic capabilities. Klebsiella pneumoniae has excellent starch degrading capabilities. And you have actually tested positive for it. I think your strategy of limiting starch and sugar is a good one. If you don’t get results, I recommend you try the Fast Tract Diet which focuses not on “refined” carbs, but rather carbs that are most likely to escape absorption and provide fuel for organisms like K. pneumonia. As for using LDN, Art is the expert here, but just keep an eye out for the most common side effects: “gastrointestinal complaints such as diarrhea and abdominal cramping.”

ps: You may have read this review, but just in case, here’s a link. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jir/2013/872632/

Thanks for this great info. I also came looking for AS and klebsiella information and was shocked and pleased to see that you mentioned them specifically. I think for now I’ll stick with my low carb, no starch diet as that’s the only way I’ve gotten relief from my IBS symptoms.

On board with that Christy. Thanks for posting.

So where are the scientific studies on resistant starch? I’m particularly interested in any proof of a positive effect (if any) on fasting blood sugar. Everything that I’ve read seems to be anecdotal.

I think I’ve read an effect on FBG, but can’t recall where.

https://jn.nutrition.org/content/142/4/717.long and https://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/82/3/559.full show improved insulin sensitivity etc but improved FBG didn’t show up.

https://caloriesproper.com/?p=4121 points to https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22815837 which did (just) show an improvement – perhaps that’s my recollection.

Yup, that was it. 4 weeks of 67 grams Hi-maize 260 (= ~40 grams type II RS). FBG 5.0 vs. 4.8 mM (p=0.049).

Hi Reub,

I realize this is a mixed bag and both the quality and quantity of studies are limited. Here are a couple of references. Also have a look at the last link which is a review. Table 8 lists numerous studies.

Raben A1, Tagliabue A, Christensen NJ, Madsen J, Holst JJ, Astrup A. Resistant starch: the effect on postprandial glycemia, hormonal response, and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994 Oct;60(4):544-51.

Behall KM1, Hallfrisch J. Plasma glucose and insulin reduction after consumption of breads varying in amylose content. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002 Sep;56(9):913-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-3010.2005.00481.x/pdf

The glycemic index of RUMPS looks to be effectively zero (or less) at https://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/60/4/544.long Fig 1.

True, but aren’t those other fermentable materials generally ignored because they aren’t all that great at fermenting into SCFAs like butyrate? I thought that’s what the “carbohydrate gap” is all about. It’s hard to imagine getting much butyrate production without fermentable carbs. Additionally, I’d imagine feeding gut bugs mucus would just diminish the gut barrier, so wouldn’t it be best to keep that at a minimum?

Good thoughts Duck. Don’t have all the answers, but I recall looking at some (boring) metabolic pathways awhile back showing that bacteria can make butyrate along with some isomers of butyrate (utilizable by enterocytes) from various amino acids. So you might not make as much from protein, but you still do make it. As for nucleic acids, don’t know for sure, but you might check check out the Kegg pathway https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?bprs00030. Mucus is 3/4 carbohydrate side chains that I would imagine is fine for making butyrate but only bacteria with glycosidases can free up the carbs for use. Many bacteria can’t do this, but interestingly, Bifidobacteria bifidum and Ruminococcus torques can. As for using up mucus, that is pretty speculative. You could also speculate that feeding key gut microbes is a function of mucus during fasts/starvation or when consuming mostly animal based diets. What do wolves do? Perhaps mucus helps ensure that the mucosal (adherent microbes) are taken care of.

Really? I thought a lack of mucus is a significant contributor to leaky gut?

I would think that the more mucus you have, the more intact the gut barrier is.

Obligate carnivores consume lots of raw, fresh, whole animals that are rich in prebiotic glycans. Researchers call it “Animal Fiber” and the fresh skin, cartilage, collagens and prebiotic glycans get fermented into SCFAs.

The problem with modern “wolf” diets is that they lack these fresh postmortem prebiotic glycans and they lack the raw enzymes (lipase for digesting fat, just to name one) that make digestion of these components easier. In other words, the wolf doesn’t need to waste energy creating a lot of enzymes since the enzymes are already present in the fresh postmortem animal.

And as some of these glycans are easily assimilated into the wolf’s body (collagens, mucins, etc) they appear to excuse the body from having to produce their own versions of those compounds, thus freeing up energy to produce the much needed glycans, like mucin. Interestingly, this appears to be what the Inuit and Masai did when they consumed their prey raw.

So, I don’t see why we would equate a Western low carb diet with that of an obligate carnivore. They are totally different.

Very interesting perspective Duck. What do you consider a Western low carb diet in grams of carbs per day?

I was under the impression that studies tend to classify “low carb” as anything under 100g of carbs/day. And “very low carb” as anything under 50g carbs/day. Moderate carb would be just above that.

From reading about highly-carnivorous humans — even cannibals for that matter — was that they always ate their meats raw. Even homo erectus, who was well known for relying heavily on meat, was not believed to have cooked its foods.

There had to be a reason that every highly-carnivorous culture ate so much raw meat.

And it gets even weirder. Here’s an individual that kills and butchers his own animals and has been eating raw animals for five years. He says it fixed his gut problems and makes him feel great. The anthropological evidence suggests that’s how “low carb” cultures always did it.

In fact, I can’t find a single low carb culture that ate lots of cooked meat!

Also worth noting that when Jeff Leach visited the Hadza, he observed one of the hunters kill an animal and within minutes the hunter was inviting him to consume the raw stomach and lightly singed colon of an impala. Both would have been particularly rich in prebiotic and pre-formed glycans. In other words, he would have been consuming preformed mucins had he eaten it.

So, I just can’t see how we can use these cultures or obligate carnivores as an excuse to eat lots of aged and cooked steak. Doesn’t seem to be in the same ballpark from my perspective.

Norm,

In terms of lowering Firmicutes and increasing Bacteroides, one needs to consider glycobiology. Most of the known prebiotics are glycans. There are millions of different glycans (together known as the “glycome”) with millions of different roles, but all they really are are just carbohydrates attached to proteins or fats or other macromolecules. As I’m sure you know, mucin-2 is a key glycan in the body — it’s a protein that is 80% sugar by weight. Many glycans are polysaccharides or oligosaccharides linked to a protein or fat molecule — so you can see why they are a prime target for gut bugs. When the link between the glycans and their parent fat or protein is cleaved in the digestive tract, the glycan (which tends to be indigestible) becomes freed. It turns out that Bacteroides secrete a lot of glycan-degrading enzymes. Firmicutes don’t have as many.

The glycome is enormous. There is a human milk glycome, with over 200 different glycans. There is a food glycome, where millions of glycans exist in our food supply.

Interestingly, raw animal skin, cartilage, raw intestines and raw muscles contain a lot of prebiotic glycans. Raw animal parts, particularly those ingested immediately after postmortem, are a very good source of glycans. However, the meats we buy in supermarkets and from butchers are missing many of these glycans since lactic acid producing bacteria quickly degrade them during the long chilling process, which tenderizes the meats we eat. Cooking also tends to degrade any remaining glycans as well. This shouldn’t be surprising since you can’t really cook prebiotics without destroying most of them.

It’s worth noting that every carnivorous animal and every highly-carnivorous indigenous culture that ever walked the face of the Earth ate lots of raw animals and raw meats. This suggests that the evolutionary low carb diet is actually a raw meat diet, which the Inuit and Masai were well known to have consumed.

At any rate, it turns out that polyphenols tend to be glycans as well. And it turns out that eating polyphenol-rich foods seems to bloom Bacteroides and suppresses Firmicutes.

You will note that Grace has recommended high ORAC foods/supplements for treating SIBO. High ORAC foods are rich in polyphenols — which makes them prime prebiotic targets for Bacteroidetes which are particularly adept at degrading glycans.

So, some of those glycans just become prebiotic food for the Bacteroidetes, and some of those glycans become other end products of colonic metabolism that can be assimilated by the body. So, when the polyphenol glycosidic linkages are cleaved by the microbiota, the ones that aren’t eaten by the gut bugs become “phenolic compounds” that can be absorbed by the body. It’s another example of our a symbiotic relationship with our mirobiota.

As I said before, there are millions of different kinds of glycans in the glycome. And again, some of them are just absorbed directly by the body. For instance, glycosaminoglycans (or “GAGs”) are found in all sorts of foods. Collagen hydrolysate, skin and cartilage are all good sources of GAGs. Wild blueberries have GAGs in them as well. The GAGs from wild blueberries appear to be cleaved by Bacteroidetes and seem to get assimilated into aortic tissues.

What this also means is that dark chocolate, raw mushrooms, tea leaves, vinegars, lemons, red wine, cocoa, flax seeds, olives, dark berries and raw herbs all have prebiotic targets and microbial metabolites in them. Do a search on virtually any of those foods and you’ll find a “surprising” article about researchers discovering prebiotic targets in them. But, it’s really not so surprising when you understand that these foods contain lots of prebiotic glycans.

When it comes to prebiotics and polyphenols, keeping them raw and undenatured is helpful for preserving their glycans. The problem seems to be that it’s a challenge to eat significant quantities of these glycan-rich foods, particularly in their raw form. And therein lies the conundrum in the Western world.

It’s worth noting that including some polyphenol-rich ingredients (particularly natural acids/vinegars) with carbohydrates have been shown to significantly lower the GI of those foods (sounds like a prebiotic effect, doesn’t it?).

Additionally, some keen thinkers have often suspected that polyphenols have prebiotic properties, but now you know why. Other than the career glycobiologists, there seem to be only a few handful of people on the planet who are aware of this glycans-as-prebiotics concept. See, you learned something else new! ;)

Kidding aside, I think the conversation should probably be less about “RUMPS” and more about how to maximize SCFA production and modulate microbiota composition. That’s the real goal here, isn’t it? “RUMPS” is just an easy/cheap way to maximize SCFA production. To my knowledge, obligate carnivores and carnivorous cultures produced their SCFAs by consuming lots of raw glycans from eating whole raw animals. That’s why they don’t have a “carbohydrate gap.” If you have any other good ways to achieve good SCFA production, we’re all ears!

Thanks for the info on glycobiology Duck. Need to read up on that. As for needing more SCFAs in my gut, I’m not sure about that at all. I was looking over some of the literature on in-vivo levels and found it quite confusing. Do you know what the typical levels are / should be? I understand there is quite a bit of variation depending on where in the intestine you sample and also the problem of them being metabolized or transported as soon as they’re made. Some in-vitro studies talk about straight up mM concentrations where some in-vivo studies used mM per day or mM per kg. Also, I read one study where dietary changes that altered the microbiota showed no change in SCFA levels. Honestly, I would like to learn more about why we need to actively eat specific types of foods or take supplements to increase SCFA levels.

I would love to pin down our exact need for butyrate, too. Lots and lots being written on butyrate lately–enhancing MUC gene expression and all sorts of stuff.

The thing that gets me, in the US and western diets, normal fermentable fiber intake (traditional sense, not FP sense) is less than 10g per day. All the studies that increase it to around 40g per day show lowering or pH, increase of SCFA (particularly butyrate), and growth of beneficial bifidobacteria.

I’ve looked at quite a few stool sample reports lately, and hardly anyone has any bifidobacteria. A couple studies say it comprises less than 4% of adults microbiome, but mostly what I see is zero%.

Seems to me a gut that favors the growth of bifidobacteria is a healthy gut. Only a few things really make it grow well…RS, inulin, momma’s milk.

Many other foods can make it thrive once established: FOS, dark chocolate, coffee, polyphenols/glycans of all sorts.

But it seems to me that so many people have a gut that is just plain hostile to bifidobacteria.

Agreed Tim. Much work to be done. The one thing I do like about Bifidobacteria is most species are homolactic fermenters producing only lactic acid and no gas from carbs which translates into fewer GI symptoms.

But some of the other claims have me wondering – colon cancer for instance. Don’t we need to firm up the connection before we go off in what could be the wrong direction? My last article included this: Two species of bifidobacterium (B. longum and B. angulatum), as well as Bacteroides were “significantly associated with high risk of colon cancer.” (Moore WE1, Moore LH. Intestinal floras of populations that have a high risk of colon cancer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995 Sep;61(9):3202-7.).

So here we have two very important groups being found at the scene of the crime – innocent by-standers perhaps? Interesting that both groups were reduced in IBS. Does that mean people with IBS will have a lower rate of colon cancer? I tend to doubt it. They also found that bacteria that produce lactic acid (not butyrate) were associated with low cancer risk. Maybe we should go after lactic acid bacteria?

And this: A study that specifically looked at the protective effect of resistant starch in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer found that resistant starch had no detectable effect on cancer development (Mathers JC, Movahedi M, Macrae F, Mecklin JP, et.al. Long-term effect of resistant starch on cancer risk in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: an analysis from the CAPP2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012 Dec;13(12):1242-9.)

– Too many questions, not enough answers.

My n=1 experiment w/ PS was no bueno. RA quickly came out remission and wrecked havoc. Crazy vivid dreams were the only positive but my sleep sucked and these dreams were not always pleasant.

I’m not surprised Johny. Here’s a link talking about carb loving Prevotella copri and RA. https://digestivehealthinstitute.org/wp-admin/post.php?post=1796&action=edit&message=1. Can’t comment on the vivid dreams. Haven’t had the experience.

Too bad you don’t have a reader/commenter who knows more about Bifidobacteria than any human alive and even wrote a book about it, huh Bill L. ?

I just looked over a uBiome report for a friend, it showed that the average sample had less than 2% bifido. The American Gut project showed similar–and these represent thousands of samples.

Babies have nearly 90% bifido until weaned. Ancient coprolite 16S rRNA samples showed high levels of bifido from 10,000 years ago and as recently as 100 years ago.

Seems like the only way to get levels above 5% is to eat a ton of inulin or RS. Jeff Leach had 5% on high inulin diet, I had 12% on high RS diet. Just saying this for ‘interesting insight’. No hidden agenda. The RS studies predicted a high concentration of bifido on an RS supplemented diet.

I’m hoping it’s a clue to better health for people. Lots of folks spending money on bifido supplements, yet not getting large bifido populations. I’m betting that ancestral populations all had high bifido counts and that the bifido in some way contributes to better guts, or is at least a canary in the coal mine.

I wonder what a famous Bifido author would say?

For starters, 12% is officially the highest bifido count I’ve ever encountered!

When it comes to colon cancer, it’s hard to say, but I’m leaning toward: no strong relationship. As Norm mentioned: in the Moore study, bifido was ‘caught at the scene of the crime,’ and Mathers showed no effect of long-term RS2 supplementation (HAMS, Novelose)… and this Gueimonde study showed *less* bifido in colon cancer (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17663515). So it’s all over the board, which to me suggests no relationship.

I think the best evidence for prebiotics is in IBS and related conditions; the focus should be on identifying which subgroups stand to benefit from supplementation.

edit: it appears as though a 1:1 blend of Novelose 240 (RS2) and Novelose 330 (RS3) was used in the Mathers study.

Perhaps the way to get bifidobacterium in the diet is to ingest it through sauerkraut and other fermented foods daily. Increase the numbers with good soil.

Nice work, Norm. Good to see you working with Tim and Richard to help people. Resistant starch has been beneficial for me and I’m grateful for the efforts of you guys.

Paleophl, Long time. Thanks and welcome.

Thank you, great article and even greater comment section with Duck The Eyeopener!

Btw, Duck, as a tip for a next topic worth some deep exploration: what about some truffles?

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2013/620451/

Gemma. Great find! I had no idea that truffles stored their energy as glycogen. That’s pretty cool. Too bad they cost so much. I also remember reading that the inferior chinese truffle has tainted the European truffle market.

Glycogen: any mushroom, not only truffles. Have you read The Lord of the Rings? “It is said that Hobbits have a passion for mushrooms, surpassing even the greediest likings of Big People.” :-)

Also, just have to admit: I’m very excited about Tim Dinan’s work on the gut-brain axis (eg, PMID 23910373 & 23759244).

I love this article and the educated discussion in the comments. It is by far the most objective assessment I have seen. I totally get why everyone is excited about the potential for RS, but true scientific research is slow work, and it will be years – maybe decades – before we really understand its effect on the diverse microbiome out there. I’m someone with RA who finds RS inflammatory. I do a combination of GAPS and AIP and have been flare-free for over a year, with no need for immunosuppressant or steroid medication, so I’m very happy with the results of diet and quite comfortable living without RS in my life.

I noticed at the start of your article you said that one of the claims of RS is that it’s an immune stimulant. I wonder if that’s one reason it harms some of us with AI, whose immune systems are prone to overactivity to begin with?

I’m also fascinated that you found some studies calling into question the universal benefits of bifidobacteria. Since I’m also casein-intolerant, I’m aware my bifido count must be quite low, so I bought some bifido-only probiotics and had an inflammatory response to them, similar to a food intolerance reaction. It caused joint stiffness and a negative gut-brain response where I felt a cloud of depression descend, which simply doesn’t happen to me. I’m one of the lucky people with positive emotional mindset as my norm. So that was completely unexpected and makes me wonder if the reason I have trouble with RS isn’t just that it feeds pathogens, but that it feeds bifido, which my body for some reason reacts against. Again….more questions than answers.

One note: just because I have a negative response to RS doesn’t mean I think all people with AI disease should avoid it. I have lots of friends in the Paleo AI community and some of them do quite well with RS. The more I learn about dietary healing, the more I see how unique we all are. I’m a big believer in n=1, and wary of n=everyone.

Thanks Eileen for your thought provoking comments. I noted the claim that RS is an immune stimulant, but don’t personally know of evidence supporting this. But your idea is plausible. One of the best groups of bacteria for maintaining tolerance is the Bacteriodes, B. fragilis for instance, with it’s miraculous zwitterionic polysaccharide A. And it seems to do well on an animal-based diet. Also check out the link I just posted above on RA and Prevotella copri.

Norm,

I first left this on William Lagokas’ post: Gluten vs. gut bacteria, Op. 78, and I’ll add a bit to it now. The post, which is spectacular, is about how increasing bifodobacteria reduces inflammation caused by gluten; in part:

My experience:

Further, commenter George Henderson posts a link to this paper:

Fascinating!

How do you like dem apples?

– – – – –

To sum up: I’ve eaten wheat at every single meal for at least three weeks precisely to test if, as a doctor and I suspected, it was giving me the heartburn, since the worst episodes of that were after eating high-wheat meals; I didn’t respond to a PPI but did to an histamine H2-receptor (ranitidine) in large (up to 600 mg/day!) doses (which the doctor says has anti-histamine properties, and led her to suspect that’s why it was effective, but the PPI not); the traditional GERD triggers such as caffeine, acidic food, and the like didn’t affect me; and my mom had celiac disease proper.

The plan was at the end of a month, to test for gluten sensitivity.

But the plan has gone awry—stymied by resistant starch. My heartburn is much reduced as is my antacid dose—yesterday none again, not for the first time. After. Eating. Wheat. In. Quantity. At. Every. Single. Meal. For. Weeks.

About six weeks ago, I’d begun the raw potato starch, just a tablespoon on average per day. (I’ve since bumped it up as of two days ago, and added other things to my “Essential Slurry”.)

It appears the prebiotic has upped my Bifodobacteria and made me much, much less sensitive to gluten … as, unknown to me at the time, science has shown Bifodobacteria does.

So I will probably get a false negative result if and when I test for gluten sensitivity.

Further: Food cravings have gone away … for the first time ever.

P.S. My operating theory is as above, but alternatively, perhaps it helped with SIBO, hence the betterment of symptoms. Either way, there’s little doubt to my mind that RUMPS and other prebiotics can, for many people, help their microbiota in profound ways. I’m increasing my dosage, for what it’s worth.

Great post Christoph, There may just be more than one way to skin this cat. I do believe prebiotics are a double edged sword. In one study I talk about in Fast Tract Digestion, fructose oligosaccharide (FOS) actually triggered acid reflux in healthy subjects. I will take a look at the refs you posted for sure. It is interesting that Bifidobacteria are one of the bacterial types observed to be reduced in IBS subjects. I’m interested to see how your experiment unfolds in the coming weeks.

For the record, I was not diagnosed with SIBO. But definitely needed ranitidine for years. And haven’t taken it for a few days now. So that’s interesting.

Hi,

I didn’t know where to ask this. The forum doesn’t seem to be working.

On the first day of the diet, the lunch is caesar salad and calls for 1 small head of romaine per person. About how many grams would this be ?

On day 5 for dinner, you recommend only 1/2 cup rice until symptoms are under control. Is that cooked or uncooked ?

And generally, in the fermenation tables, are those values for cooked or uncooked foods ?

Thanks,

Susan

Hi Susan,

The lettuce has almost no FP – maybe 1 to 1.5 grams. The rice refers to 1/2 cup cooked. The idea is to really watch the starch early on – even the low FP variety until SIBO is more under control. Even easy to digest starch can be malabsorbed with aggressive SIBO.

Thanks for your great work Norm…you are on the cutting edge. I wonder if you have considered the work of Andrew Kim and Ray Peat….both of these guys support your contention that fermentation should be minimized…..exactly the opposite of what Mr. Leach seems to be saying. Very confused. And no one seems to be looking at the problem of “persorbtion” as it applies to RS. From Kim – https://www.andrewkimblog.com/2012/12/are-starches-safe-part-2.html

Hi Hcallahann44, Tatertot Tim Steele addressed the persorption topic here: https://www.marksdailyapple.com/forum/thread73514-109.html#post1442383

Both Norm and Jeff Leach have provided interesting contributions toward explaining the big picture. I have also read some of Andrew Kim and Ray Peat’s writings and also found some of their work quite interesting. One of the more interesting things was that when I increased my consumption of prebiotic foods to closer to ancestral levels, my body temperature and resting heart rate moved toward the numbers that Ray Peat advocated, with my body temperatures now matching Ray’s ideal range. Resistant-starch-rich foods did more than any other prebiotic source or other type of food I’ve tried so far to give me Peat-recommended results, including tropical fruits. I actually wish it had been yummy tropical fruits, of which I still eat more than most people do (and I often have to tell the cashiers what some of them are). :)

Of course, YMMV, and I take Norm’s cautions seriously.

Thanks Paleophil…I have been scouring the internet trying to find an answer to this so your response was extremely helpful!! I was on a VLC diet for many years and developed unconquerable diarrhea. I kept cutting the carbs even lower in an attempt to address it…following the Life Without Bread guys. Finally I caved and tried potato starch…and within a week had perfect poop. Of course the Peat crowd rained on my parade. You seem to be one of the most informed authorities out there on these issues…would you consider a private paid consult?? Curious to hear that you are using Prescript Assist probiotics…some say these are harmful due presence of Bacillus Subtillus…and organism that can be difficult to eradicate in the immunocompromised. Would love to pick your brain on the RS stuff sometime. Thanks again for your post!

Hi Hcallahann44,

I used 1 bottle of Prescript Assist and now am trying Primal Defense Ultra. Haven’t noticed anything from them.

I’m not an authority. Tatertot knows more about the topic than me and he answers questions for free, thus killing my chances for a profitable consultancy. ;-) He has answered questions in the past at the Mark’s Daily Apple Forum and you could also PM me (Paleophil) there if you like.

I have noticed a small benefit from Primal Defense Ultra – eyebrow dandruff that I’ve had for decades disappeared since I’ve been taking it. I still have some scalp dandruff, though.

The real question that remains unanswered is— do we need to eat as many types of fermentable fiber as possible to optimize gut function….or do we need to minimize consumption of fermentable fiber to reduce endotoxin and achieve optimal gut health. Ray Peat and Andrew Kim and I assume Norm R. falls in the latter camp. Jeff Leach and Tatertot in the former? Frustrating that these two positions are diametrically opposed. Would be nice to know the answer!

Lots of ways to phrase the last part of that sentence:

…to feed our microbiome?

…to create more SCFAs and improve acidity?

…to crowd out pathogens?

…to produce a vitamin factory in our guts?

…to improve nutrient absorption?

…to improve neurotransmitters?

But if you have a bad gut and your goal is to minimize endotoxins, then those benefits may not be first on your list.

Good question Hcal. Curiosity and effort to find answers may help replace some of the frustration. I do think the answer will be different for different people. This study for instance (https://wrd.cm/1ip93V0) is a good tip of the iceberg story on how the amazing diversity of our gut microbiota matches and adjusts to the changes in our diet. And it includes a few surprises, for instance these hunter-gathers have almost no bifidobacteria and their bacteriodes have not been characterized.

I wouldn’t get too excited. Unfortunately, the researchers stored the samples in alcohol. So, the bacterial proportions are likely invalid.

https://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2014/04/15/first-look-at-the-microbes-of-modern-hunter-gatherers/

The article elaborates:

Interesting Duck. I would agree if they were trying to preserve viable organisms. Instead they were preserving the genetic material from the samples (16s ribosomal DNA) and SCFAs for extraction and analysis. They validated the methodology with human fecal samples (Germans). Check out the methods section at the end of the paper.

I hope it’s true, or if not, the re-do the tests. These are invaluable.

If it’s true they have no bifido, it makes me wonder if their babies do…surely they do? I wonder when they lose it.

Also, if the graphs in the study are accurate, maybe we should be looking at the massive blue bands at the bottom of the charts that both groups share and search for commonalities that we all share and then see if those are missing in people with say, GERD, IBS, AI diseases, etc..

The fact that they had no bifido wasn’t all that shocking to me, many, many Americans don’t have it, either. It must be a very temperamental species.

Norm,

You would know better than I, so I just thought it was interesting. Though, the quote from Rob Knight that the data isn’t valid should be a warning flag. Rob Knight sure seems to know a lot about DNA:

https://knightlab.colorado.edu

Nevertheless, Jeff Leach’s frozen poo samples, which are still being analyzed should give us more clues.

I also suspect that the pH of their guts allows them to have a wider variety of potential pathogens. As fermentation drops (as in a low-fermenting Western gut) alkalinity rises and there are species that are known to proliferate and turn pathogenic in an alkaline gut, but are generally benign in an acidic gut. So, when we talk about the species they have, the context of the gut, in terms of pH probably matters a lot.

I think it should be looked upon from a broader perspective. Read the study till the end. Interesting quotations:

“The Hadza neither domesticate nor have direct contact with livestock animals. Thus, as they lack exposure to livestock bifidobacteria, this raises the question of whether the necessary conditions for interspecies transfer and colonization of bifidobacteria do not occur for the Hadza.

It is important to note that while bifidobacteria are considered a beneficial bacterial group in western GM profiles, their absence in the Hadza GM, combined with the alternative enrichment in ‘opportunistic’ bacteria from Proteobacteria and Spirochaetes, cannot be considered aberrant. On the contrary, the Hadza GM probably represents a new equilibrium that is beneficial and symbiotic to the Hadza living environment.

In our study, more than 33% of the total Hadza GM genera remain unidentified. Such taxonomic uncertainty holds exciting prospects for discovering yet unknown microbial genetic arrangements.

We expect that detailed study of the function of this GM community will expose a greater number of genetic specializations for degrading polysaccharides than what is currently found in other human populations.