A new study by researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine published in the September 2013 issue of Nature proposes a mechanism for how disease–causing microbes such as Salmonella and C diff often thrive when people take antibiotics. Soon after someone takes antibiotics two things happen: The number of friendly gut bacteria is dramatically reduced and the amount of available carbohydrates in the gut is dramatically increased. According to the authors, the extra carbs and fewer friendly gut bacteria allows the bad bacteria to take over.

It turns out that friendly gut microbes are able to cleave sugars including fucose and sialic acid from mucus (mucus is made of a variety of sugars) that cover the entire surface of the gut. With the help of other friendly microbes these sugars are normally broken down and shared. But when people take antibiotics many of the bacteria that cooperate to break down and consume these sugars are lost and bad bacteria (pathogens) can then use these sugars themselves to grow and become established.

I found this paper interesting because it lends support to the idea that fewer excess carbs in the gut leads to more competition which favors indigenous gut microbes over bad or pathogenic bacteria. A good example in the paper likens friendly gut microbes to your lawn. “It is thought that our commensal, or friendly, bacteria serve as a kind of lawn that, in commandeering the rich fertilizer (carbs) that courses through our gut, out-competes the less-well-behaved pathogenic “weeds.” The more healthy grass you have, the fewer weeds will be able to become established.” But if you were to spray your lawn with roundup (like antibiotics) and continue to add fertilizer, soon you will have a weed-filled yard. According to the authors: “Resident microbes hold pathogens at bay by competing for nutrients.”

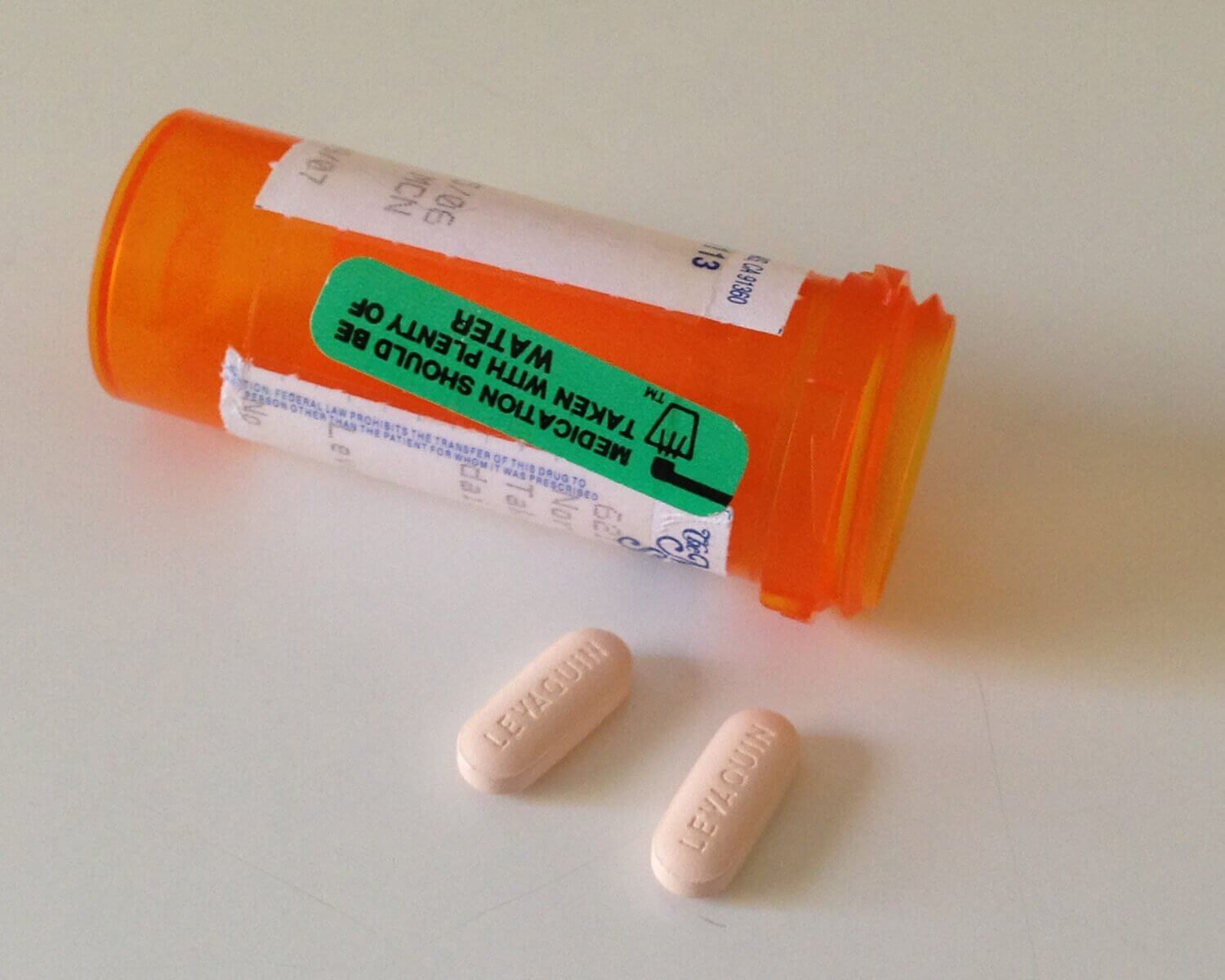

While we may not be able to control the amount of sugar chains comprising our gut mucous supply, there are two things we can do: 1. Take antibiotics only when they are absolutely necessary. 2. Limit the overall amount of difficult-to-digest but fermentable carbohydrates in our diet. That’s the strategy of the Fast Tract Digestion book series for control of SIBO-related conditions such as IBS, GERD, Rosacea and many others. One day, this diet strategy may prove to be supportive of people who need to take an antibiotic. Clearly excess fermentable carbs is not something you want when you are about to drastically inhibit a large number of your friendly gut microbes – which is what happens when you take antibiotics.

Update: Here is an interesting report on how another bad bug, enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC), uses a chemical sensing system to manipulate a friendly gut microbe (Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, also the subject of this blog) to serve it up a nice meal of fucose sugar.

Hi Norm, interesting post, as usual.

On an unrelated point, can I ask does all fibre have a high fp? I’d prefer to include some in my diet ideally, such as psyllium husk.

Thanks!

Hi Colin,

Thanks. Good question. I talk about the relative fermentability of fiber types in the Fast Tract books. I include all fiber in the FP calculation because, by definition, Fermentation Potential is just that – if there is potential for a carb type to be fermented it needs to be included. Having said that, some fiber types are more difficult for bacteria to rapidly break down and less likely to drive symptoms. Lignin and cellulose are the least fermentable. I would say go ahead and experiment with the psyllium husk if you want. But choose a “sugar free” product. I know that Metamucil is now available as a sugar free product. Otherwise, it contains over 20 grams of sucrose per day.

Thanks Norm, much appreciated!

Great write-up! I am so happy to see our understanding of gut microbes growing by the day. The advice you give regarding antibiotic recovery is spot-on. So little attention is given to this. No wonder most rounds of Rifaximin only work in the short term.

Thanks Tim. Interesting research. Of course, there are so many other issues with antibiotics as well. Though often times life saving medicines, the gut takes the brunt with less diversity after treatment, the risk of C diff and the emergence of a variety of other resistant strains – often passed on to other people and a range of other side effects and health risks, depending on the type used.

Hi,

I was wondering if anybody has done research into the possibility of swallowed air being at least partially responsible for reflux in individuals for whom belching is a dominant symptom. In my case I had an esophageal manometry done and the attendant noted that I swallowed a significant quantity of air for some reason, although all other test results were perfectly normal. It could potentially explain the abnormal/excessive belching symptoms in many people with reflux (in theory) and would certainly facilitate stomach acid and contents going “the wrong way”. What do you think?

Hi Doug,

Swallowed air was once considered to be the main source of gas in the GI tract and it is possible that some of your own intestinal gas is swallowed (I would think you would notice). But newer research including my books provide overwhelming evidence that the predominant source of intestinal gas is from gut microbes fermenting undigested carbs. Even the latest volume of the Textbook of Primary and Acute Care Medicine, page 1192 in the chapter on Intestinal Gas Complaints states: “Dietary alterations to reduce gas require the elimination of: sugar alcohols, fructose, oligosaccharides, resistant starch, fiber and lactose. I though it was funny what they wrote next, essentially writing off dietary control of intestinal gas: “Unfortunately, such a diet is found to be relatively unpalatable by the average American”. And that’s where my books come in.

Wow. I wonder when that textbook was originally published with that particular quote. They could potentially have arrived at the same conclusions that you do in your research books years and years ago, saving hundreds of thousands of people from digestive pain and aggravation in the process. But, alas, they seemed to have written it off as though it were impractical, and probably advised taking a prescriptive pill instead – which likely only further exacerbated the problem (sure did for me).

Unrelated follow-up question about your Fast Tract book – broccoli is listed as low FP but it does tend to cause lots of gas for some people. Is that due to unique enzyme issues or other reasons in those particular people? Just looking for explanations, other than food sensitivities or frequently missing enzymes (like those needed to process lactose) to explain that type of phenomenon.

Thanks!

Doug

Doug, It came out in 2004 – but I just recently found it when I borrowed the text book from the library while putting together my caveman talk for the Ancestral Health Symposium last August. Yes, they might have figured it out with a little more effort. Note they did not associate acid reflux with their intestinal gas observations. But all the pieces were available – even the connection between GERD and intragastric pressure.

Broccoli does have some fiber / FODMAPs so some gas might be possible. But even the FODMAP diet listsbroccoli as OK for small portions. I would say “use your judgement and limit the portion if concerned”. I typically consume about 1/2 cup and never had a problem – even when I eat more.

Hi Norm,

I’m having trouble deciding on whether eating fermented foods such as sauerkraut would be good or bad for reflux/IBS, having read your book on reflux. On one hand we’re obviously trying to avoid fermentation in the gut itself, so it seems a bad idea. But on the other hand it’s supposed to add digestive enzymes and “good” bacteria to our guts – which would theoretically be a good thing. And it’s already been fermented by the time that we eat it. What’s your take on this?

I will add more on this in the next book. Definitely good as long as there is not a lot of added sugar. The example of sweetened yogurt (FP 20 something), vs. unsweetened or non sugar sweetener is about 2/3 less in FP. In general, fermentation depletes the sugars as the fermentation process occurs so you get a low sugar product that is often low carb in general as well. You also get various probiotic strains, most of which are gut healthy. Note: there are some gas producing strains which is why some complex probiotic blends cause bloating.

Thanks Norm! Is there a list of the gas producing probiotic strains so we can look to avoid them when shopping for probiotics? I was starting to eat organic non-pasteurized sauerkraut (https://www.belandorganicfoods.com/en/organic-products/kartheins/overview) which I believe they add lactobacillus to in addition to whatever would normally be present. I’ve also read a bit about some new soil-based probiotics such a Prescript-Assist. Any recommendations as to what the right approach might be to re-populate the gut with healthy flora? THANKS!

If you want to try a probiotic, I would recommend sticking with probiotics containing lactobacillus and bifidobacteria. You get lactic acid produced (increases gut acidity which might limit hydrogen gas production) and some good enzymes (help break down lactose and even gluten). If they contain any other bacterial types, one should assess whether or not they are “gas producing” (called heterolactic fermenters) strains. You don’t want excess symptom-causing gas.

Interesting post.

Do you think it is possible that this is one of the ways antibiotics can contribute to SIBO. That is, by changing the normal flora of the small intestine to more pathogenic and/or gas producing bacteria ? In my case, my problems started after a round of antibiotics, both IV and oral. I’ve heard the same from many others.

Absolutely Susan. I do. There is no question about the connection between IBS/SIBO and antibiotics. There are many people on this site who report the same thing you have. Antibiotics can be lifesaving drugs without question. But the long term effects on our gut microbes deserves much more study. My advice is only take antibiotics when absolutely necessary. Here is an article on taking antibiotics for IBS (SIBO).

Thanks Norm. I’m being evaluated by a well respected gastroenterologist. So far, he has found fructose intolerance and am waiting on the SIBO results. The FODMAPS diet is not helping, in fact, it may be making me worse. I think I know now why – the FP of the rice etc in the diet. I’m one of the ones with severe bloating and belching so I’m a little concerned I may even have overgrowth up near where the glucose is absorbed. Doing the FAST TRACT diet should give me an answer to that, I think

Agreed. Let me know what happens and good luck Susan.

Susan’s comments bring two questions to mind. 1) If the fast tract diet is implemented, what’s to prevent the bacteria from migrating north in our intestines, where simple sugars would be getting absorbed, and feeding there? 2) Would an “erase and replace” regimen work, where you eradicate the bad guys then re-populate the gut with good guys like bifidobacteria?

I’m also in the belching and bloating boat and am wondering if the bacteria are feeding closer to my stomach and producing gas there which then leaks back into my stomach as the shortest escape route. I plan to get a stool analysis then eradicate using appropriate measures, preferably natural like all icon and peppermint. But keep the fat tract dieting place while I’m doing it.

Doug,

You have peristalsis keeping things moving away from the stomach and a multilayered immune system and stomach acid all working against overgrowth. The Fast Tract Diet supports these systems by limiting fermentable carbs.

Erase and replace might work if you could “replace” with a full complement of gut microbes as with a fecal transplant. Otherwise, not an idea with much merit, especially if you bring in antibiotics to do the job.

That was supposed to read allicin not “all icon” :-)

Thanks Norm. Good info. What do you make of the controversial soils based organisms for gut health? Have been reading a lot about the gut microbiome lately, fascinating stuff! Really is a key to our health along with diet and exercise. Wish I understood how to better care for mine! The fast tract diet is a good start at correcting things though.

I have not read much about probiotics supplements based on soil. I could be missing something, but personally, I would be cautious about soil derived microbes. You likely will not all of the organisms are present. Soil serves as a reservior for a number of pathogenic bacteria and fungi. The most deadly example is Bacillus anthracis. Ingesting small amounts of soil from dirty hands, gardening etc. should be fine. But I would avoid larger amounts or concentrated supplements from soil. Just my opinion.

Hi,

Just wanted to update on my situation for what it is worth. I did test positive for SIBO in my distal duodenum. I decided to take the antibiotics and follow the diet. I am so surprised it hasn’t made a single small dent in my bloating and belching. I thought I had found the answer. I’ve since started studying “intestinal handling of gas” and am no longer convinced SIBO is causing the bloating and belching in my case but rather think there is a motility problem perhaps caused by dysbiosis (this is being studied now as is the gas handling issue). Susan

Thanks for the update Susan. Hoping for your quick recovery.

I am on long term antibiotics forTB .your articles are fascinating,but no one

seems to be able to tell me how much I should take(potato flour that is)and how,can anyone help me?

Kindest Regards John Nash

Hi John,

Hopefully, your microbiota will recover fully over time after you stop the antibiotics. I’m not sure why you think you should take potato flour.

Dr. Robillard

I think you have touched on this in other places, but what are your thoughts on managing the candida overgrowth that occurs from antibiotic use? For years, candida doctors have advocated a moderately low carb, no sugar, no alchohol, no fun, high FIBER, low GI diet. This is crazy making for those of us trying to get our guts well. My body is responding very well to your Fast Track Diet and this one seems to make a lot of sense as it limits the nutrients available to all gut microbes. However, candida docs have always made the claim that fiber increases intestinal time and lowers the amount of available sugar for candida. I am starting to think your approach makes more sense, but it goes against ALL the candida doctors. In thinking about your diet non-stop for the past two weeks, I am starting to wonder if this approach would REALLY help curtail the relapse that is so common and dreaded for people that have lowered thier candida levels and then return to the same SAD diet. Also, i think it would be so valuable for you to have a look at why candida and SIBO symptoms overlap and are commonly confused and the wrong treatment applied by holistic doctors!!

Hi Bearsmom,

I can understand low carb and low sugar. The fiber might not matter much in this case, as I don’t believe Candida has the enzymes to break down most types of fiber. But I agree relapse could be supported by a return to a high fermentative load. Another important aspect of candida overgrowth is asking why it’s occurring. Immunocompromized individuals and people taking antibiotics are most susceptible.

Thanks Norm,

In theory, candida feed on sugars, so that is why candida doctors try to tell people to avoid foods with a higher GI. This is where the confusion lies for me between your diet and traditional candida diets. I hope I am not being too repetative!

I guess I am being conservative on the FTD by eating a max of 1/2 cup jasmine rice per day and no desserts. In the back of my mind I hope I am utilizing all this food and it is not becoming food for the candida. In theory I guess it is being absorbed so not left for the candida?

From what I understand from talking to people in various gut healing forums, is that a lot of people with SIBO have candida and vice versa. According to a leading candida expert, it only takes one antibiotic pill (yes, a pill) to convert yeast in the GI tract into its fungal form which makes it much harder for the immune system to manage. I agree that lowered immunity and/or abx overuse are key. Especially if one takes several rounds of broad spectrum abx in close proximity. The thing is, I think 2/3 of Americans have some candida overgrowth, as near everyone has taken broad spectrum abx these days at least once!

I see. I get your point now. Candida diets say to avoid simple carbs because they’re easier for Candida to consume. But they’re also easier to digest and absorb meaning that fewer of them are available for yeast and bacteria to feed on. It’s a double edges sword.

Also, the Fast Tract Diet recognizes that some simple sugars such as lactose and fructose (including the fructose in sucrose) are not absorbed well by many people. That explains why both diets limit sugar.

This sentence on this page is so wrong: restricting carbs “favors indigenous gut microbes over bad or pathogenic bacteria”. Ha! Have you spent even 10 minutes reading any forum for sufferers of candida overgrowth in the gut?

Millions of people online comment that the strict anti-candida diets, which are very low carb, do NOT heal the problem. A single bite of any carb at the end of weeks of the strict diet, yes even “safe” carbs per your site, brings back the overgrowth. So much for the “indigenous non-harmful” bacteria having been favored by that diet.

Please stop with this fairy tale – we have been blamed enough for “not following the diet long enough” or “cheating”. The diet doesn’t heal anything, it just masks the problem until a single bite of any healthy carb is eaten.

The fact that you don’t even know this shows how out of touch you are with reality of these gut problems.

Hi Steve, This post is about antibiotics, bacteria and carbohydrates, not Candida.

Hi Norm,

I’m really glad that I came across this in my Google search. I was prescribed antibiotics prior to my doctor actually testing for a bacterial infection in my throat. Half way through the prescription, my doctor (or ex-doctor I should say) finally tested me for strep and mono, both of which came back negative – it was a viral throat infection. Ever since I completed the antibiotics I have had acid reflux and a lot of burping. The reflux has caused inflammation in my esophagus and I’ve been on a soft/liquid food diet as a result. My ENT has prescribed PPI’s to stop the reflux in order for my esophagus to heal. I’m reluctant to take them. Do you think I should until my esophagus heals, or will the diet in your book allow me to eat soft foods until the inflammation goes down? It’s a little disappointing that a medical professional led me down a path of unnecessary antibiotic usage, which ultimately resulted in me developing a condition that I never experienced prior.