Irritable Bowel Syndrome is linked to bacteria in our gut

The antibiotic rifaximin (brand name Xifaxin) was recently approved by the FDA for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBSd). You many wonder why doctors would recommend an antibiotic for IBS.

The idea that antibiotics may be helpful for IBS is based largely on the work of Dr. Mark Pimentel, the Director of the Gastrointestinal motility Program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Dr. Pimentel’s book, A New IBS Solution, documents his team’s research linking an overgrowth of bacteria in the gut to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The book and subsequent journal publications provide solid evidence that a technique called hydrogen breath-testing can be used to determine if too many bacteria in the small intestine may be causing a patient’s IBS symptoms. The condition is called SIBO for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

SIBO is also a factor in other digestive health conditions including celiac and Crohn’s disease, and may also be involved in systemic conditions including rosacea, asthma, scleroderma, ankylosing spondylitis (a serious autoimmune condition like arthritis), and fibromyalgia. This article also has relevance to chronic acid reflux based on evidence in my book, Fast Tract Digestion Heartburn linking acid reflux to SIBO (Could antibiotics help people with heartburn?).

Hydrogen breath-testing can detect SIBO because gut bacteria (but not human beings) produce hydrogen gas when they ferment carbohydrates. The hydrogen is absorbed into the blood and exhaled in the breath. Excessive breath hydrogen (the patient blows in a tube and the samples are analyzed at the lab), detected soon after taking a drink of lactulose (a sugar that can’t be digested by humans, but can be fermented by bacteria) is indicative of SIBO.

Dr. Pimentel’s recommended treatment approach for IBS patients diagnosed with SIBO is referred to as the “Cedars-Sinai Protocol”. Once tests are given so celiac disease, thyroid malfunction, and other conditions that could give the same symptoms can be ruled out, the patient is offered a ten day course of antibiotics. The antibiotic most recommended is rifaximin, which is FDA approved for traveler’s diarrhea caused by certain strains of E. coli, to reduce the risk of overt hepatic encephalopathy recurrence (the worsening of brain function when the liver can’t remove toxins from the blood) and now for IBSd. A second antibiotic, neomycin, is sometime recommended as well.

The treatment of SIBO itself with antibiotics is not new. Several antibiotics including metronidazole, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, amoxicillin-clavulanate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cephalexin and norfloxacin have been used for SIBO in the past. A short term study involving ten SIBO patients indicated that norfloxacin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid could be effective in the treatment of bacterial overgrowth-related diarrhea[1]. Metronidazole (Flagyl), which has potent activity against several bacteria associated with SIBO such as Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium difficile, has also been used successfully for treating SIBO[2].

The case for antibiotics

There are many situations that merit the use of antibiotics. Life-threatening infections such as (bacterial) pneumonia or septicemia – a serious bacterial infection of the blood, come to mind first, but there are many other occasions where bacteria jeopardize our health and antibiotics may be needed. Some types of bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, are particularly virulent meaning they are well adapted to causing disease and an antibiotic may be needed to control the infection. Also, some people have immune deficiencies where even routine infections can be serious. Antibiotics are also used for some chronic infections caused by bacteria, such as H. pylori, which can lead to stomach and duodenal ulcers, even gastric cancer. Treatment of IBS with antibiotics differs in that the condition is not caused by a single pathogen, but rather a general overgrowth of intestinal bacteria in the small intestine.

There are many other instances where antibiotics are not a wise choice. The best example is taking antibiotics for a cold or other illness caused by a virus. In these cases, antibiotics won’t help at all, and indiscriminate use limits their effectiveness in the future because antibiotic use provides constant pressure for resident bacteria to become resistant to the antibiotics used.

In most cases, antibiotics are prescribed when there is clear evidence that the patient suffers from a bacterial illness that is not expected to resolve on its own. Doctors often prescribe antibiotics empirically without knowing what specific bacterium is causing the problem, but when the causative organism has been isolated in culture there is a much greater chance for success, because the cultured bacterium can be tested for susceptibility to a variety of antibiotics so the most effective one can be selected.

On the surface, it would seem logical to treat SIBO with antibiotics. SIBO after all, is bacteria overgrowing in our small intestine. The logical response would seem to be “kill the bacteria that are causing the problem”. Certainly, there are circumstances where antibiotics are needed for SIBO. Situations where SIBO poses a significant and immediate health threat such as anemia, malnutrition or other serious medical conditions may require intervention with antibiotics. But can antibiotics rise to the challenge? Treatment success means killing the bad bacteria and bringing down the overall number of bacteria while not wiping out all the good bacteria. Unfortunately, antibiotics represent a shotgun approach that often causes more problems than it solves. Though I have great respect for the work of Dr. Pimentel’s team on IBS, I am not sure about the rationale for using antibiotics as a first line treatment for IBS. There may be reasons to reconsider this approach. Let’s look at the pros and cons.

Why the approach might make sense (The Pros)

- Lots of people with IBS can be helped. If the Cedar-Sinai Protocol works, it stands to help many people. There are an estimated fifty million people in the US who suffer with chronic IBS. Pimentel’s team found that 78 percent of patients with IBS had SIBO[3]. Similar findings were observed in children[4].

- Reported to be effective and safe. Dr. Pimental states in his book that he recommends rifaximin and neomycin because the antibiotics have been shown to be effective for treating SIBO and both antibiotics are almost completely contained in the GI tract minimizing side effects and drug resistance. Pimentel’s team suggests that the treatment protocol is effective for most IBS sufferers with SIBO noting that “patients’ IBS symptoms significantly decreased after a single ten-day course of rifaximin” and that “the symptom improvement lasted two months after treatment.”

- Preventing more serious consequences of SIBO. Antibiotic treatment, if successful, could help prevent more serious complications of SIBO from occurring. Like IBS, the symptoms of SIBO include abdominal pain or cramps, diarrhea, constipation, gas, bloating, acid reflux, flatulence, nausea, dehydration and fatigue. But SIBO can cause more severe symptoms including weight loss and “failure to thrive,” steatorrhea (the body’s failure to digest fats), anemia, bleeding or bruising, night blindness, bone pain and fractures, leaky gut syndrome, and autoimmune reactions. Preventing SIBO from invoking more serious symptoms and illness is important.

Reasons to reconsider treating IBS with antibiotics (The Cons)

While I support the use of antibiotics for treating serious bacterial infections, including the most serious forms of SIBO mentioned above, I have five basic concerns over the use of antibiotics for the routine treatment of IBS.

- Antibiotics lack both short- and long-term efficacy for IBS.

- Antibiotics kill both good and bad bacteria and can lead to C. diff infection.

- Overusing antibiotics breeds resistant strains of bacteria.

- Antibiotics are associated with side effects and can cause allergic reactions.

- There are better ways to control SIBO, using diets that limit fermentable carbohydrates and sugar alcohols.

Antibiotics lack both short- and long-term efficacy for SIBO

In two double-blind (neither investigators nor patients know who receives placebo and who receives the drug) clinical studies funded by Salix called Target 1 and Target 2, similar results were achieved in IBS patients treated with 550 mg or rifaximin three times daily for two weeks[5]. “Adequate relief” of IBS symptoms was 41 vs. 32 percent when both studies were averaged for rifaximin and placebo respectively. “Adequate relief” was defined as relief of symptoms for at least 2 of the first 4 weeks after treatment – not sure why relief for only half of the time is considered adequate. Relief of bloating was also measured as 40 vs. 30 percent when both studies were averaged for rifaximin and placebo respectively. While the results were statistically significant in favor of the antibiotic treatment, based on some earlier work, I had expected more dramatic results. The antibiotic only gave a 10 percent improvement over placebo.

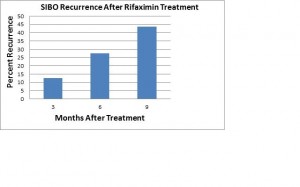

Also antibiotics are not effective for long term treatment of SIBO. A study of eighty patients with SIBO who were treated with rifaximin showed a high recurrence rate six months (27.5 %) and nine months (43.7%) after therapy[6]. Refer to figure1.

Clearly, this high recurrence rate indicates the underlying problem not being addressed fully in many cases, and the bacteria quickly grow back after treatment. One of the reasons for this lack of efficacy could be that the antibiotic does not inhibit all bacterial types overgrowing in the small intestine. And many gut bacteria involved in SIBO and IBS may quickly develop resistance against the drug (see below).

Antibiotics kill both good and bad bacteria and can lead to C. diff

The antibiotics used in the Cedars-Sinai Protocol are broad spectrum meaning they inhibit a wide range of bacteria. This is important because SIBO is not caused by a single type of bacteria but rather by the overgrowth of many types of bacteria, generally arising from the large intestine. Many of the bacterial types involved will likely be resistant to several less potent antibiotics. But there is a downside.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are indiscriminate bacteria killers. They can disturb the balance of good to bad bacteria in the intestines causing diarrhea and other problems. Whenever people take antibiotics, regardless of the reason, a large number and wide variety of intestinal bacteria are killed. This is likely the reason that broad-spectrum antibiotics can themselves lead to IBS[7] as well as inflammatory bowel disease[8]. In most cases, the natural balance of your intestinal bacteria will be restored over time after you stop taking the antibiotic, but this can take a long time, even years. In some cases, the original healthy intestinal microbial population never fully recovers.

When you wipe out the healthy gut bacteria, pathogenic or bad bacteria can take over. The worst of the bunch is Clostridia difficile, known as C diff. According to a CDC press release[9], C diff is linked to approximately 14,000 deaths every year in the US alone, mostly due to a dangerous condition called pseudomembranous colitis (a serious inflammation of the large intestine). Even more powerful antibiotics may be required to treat this condition. The biggest risk factor for C diff is taking antibiotics or staying in a medical facility which may include hospitals, nursing homes, or even doctor’s offices. C diff makes difficult-to-kill spores that are able to persist on surfaces and even the hands of medical providers. Most at risk of dying from infection are elderly patients. According to the article, treating C diff infections costs at least one billion dollars each year.

Overusing antibiotics breeds resistant strains of bacteria

One of the biggest challenges in treating SIBO with antibiotics is drug resistance. Many bacteria are naturally resistant to many antibiotics and all bacterial have the ability become resistant either through mutation or by receiving resistance genes from other bacteria. Well known examples of drug resistant bacteria include methicillin-resistant Staph aureus (blood and wound infections and toxic shock syndrome), multidrug-resistant enterococci (urinary tract, blood, and other infections) multi drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (pneumonia, blood, urinary tract and other infections) and drug resistant C diff. (diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis – serious inflammation of the colon). Drug resistance limits the usefulness of all antibiotics whenever they are used, but the problem is most challenging with SIBO because of the sheer number and diversity of bacteria that reside in the small and large intestine. As resistance to one drug emerges, SIBO and symptoms will persist until another antibiotic or antibiotic combination is found that can effectively treat the condition.

Drug-resistance and C-diff

As mentioned above,C diff often takes over after antibiotic treatment kills the majority of friendly bacteria. C diff infection is so often linked to antibiotic use that it’s commonly referred to as “antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD)”. Having lots of healthy bacteria is the best protection against C diff.

Once established, the bacterium produces several toxins including enterotoxin (toxin A) and cytotoxin (toxin B) that cause inflammation and severe diarrhea. C. diff infection can lead to pseudomembranous colitis, a potentially life-threatening inflammation of the colon. C diff is on the move in hospitals, nursing homes and even doctor’s offices. There are already many C diff strains (some from epidemic outbreaks) that are resistant to a number of antibiotics including rifaximin. This is concerning because not only is rifaximin being recommended for treating IBS, but because it has actually been used as a supplemental drug to treat C diff infection.

A study of C diff strains from a hospital outbreak found that rifampin resistance (rifampin is a close relative of rifaximin) is common (36.8% of 470 recovered isolates and 81.5% of 205 epidemic clone isolates) among C. diff isolates recovered during epidemic outbreaks at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center–Presbyterian Hospital[10]. The authors stated that “Exposure to rifamycins (which include rifaximin) before the development of C. difficile-associated disease was a risk factor for rifampin-resistant C. difficile infection. The use of rifaximin may (therefore) be limited for treatment of C. difficile-associated disease at our institution”. This finding is supported by other research showing that the same mutations in C. diff that result in rifampin-resistance also result in resistance to the closely related antibiotic, rifaximin[11]. Recently, investigators reported the selection of C. difficile resistant to the rifamycin class of antibiotics in a patient within 32 h of receiving rifaximin for the treatment of recurrent C. difficile diarrhea[12]. And the problem is not limited to the US. In another recent study, more than 10% of C. diff isolates from three major teaching hospitals in Taiwan were resistant to rifaximin[13].

Salix, who makes rifaximin also cautions on their website with the following statement: “Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) has been reported with use of nearly all antibacterial agents, including rifaximin, and may range in severity from mild diarrhea to fatal colitis. Treatment with antibacterial agents alters the normal flora of the colon which may lead to overgrowth of C. difficile. If CDAD is suspected or confirmed, ongoing antibiotic use not directed against C. difficile may need to be discontinued”.

Antibiotics are associated with side effects and can cause allergic reactions

As noted on the Salix company website, patients experienced the following adverse reactions: edema peripheral, or fluid in the tissues of the extremities causing swelling in 15 percent of patients, nausea was found in 14 percent, dizziness in 13 percent, fatigue in 12 percent, ascites, or fluid in peritoneal cavity between abdominal organs in 11 percent, muscle spasms in 9 percent, pruritus in 9 percent and abdominal pain in 9 percent.

Though some side effects are also noted in people taking placebo, the high percentage of people having side effects is a definite con in my opinion, especially given the limited effectiveness of the antibiotic for IBS. Keep in mind that more serious side effects occur, though at a lower frequency than those listed above. Web MD lists one infrequent side effect, a hernia that protrudes into the abdominal wall and 14 other rare but serious side effects. All antibiotics, including rifaximin, can cause serious allergic reactions. Potentially serious side effects are another reason to use caution and take antibiotics only when they are absolutely needed and expected to provide maximum benefit.

There is a better way to control SIBO

In some cases, correcting SIBO can be fairly simple. For example, a lactose-intolerant individual with intermittent diarrhea (caused by SIBO) may recover completely by avoiding lactose or taking the enzyme supplement lactase. But often the problem is more complex and the overgrowing bacteria has become part of the cycle of SIBO and malabsorption (see below). In this case, successful treatment of SIBO requires treatment aimed directly at the bacterial overgrowth as well as treatment to correct or ameliorate the underlying problem that allowed SIBO to become established.

Potential causes of SIBO (you likely suffer from one or more of these if you have IBS, GERD/LPR, celiac or Crohn’s disease, fibromyalgia, rosacea, interstitial cystitis, autoimmune disorder or several other SIBO-related conditions) can be grouped into different categories including:

- Motility issues

- Pancreatic insufficiency (lack of digestive enzymes)

- Intestinal villi damage (finger like projections for nutrient absorption)

- Antibiotic use

- Gastric (stomach) acid reduction

- Immune impairment

- Low ileocecal valve pressure (separates the small from large intestine)

- Carbohydrate malabsorption

If you and your medical provider can determine which of these factors is causing your symptoms you have a good chance to adopt a comprehensive treatment approach that will provide lasting relief. Each of these factors along with treatment guidelines is covered in my books Fast Tract Digestion Heartburn and Fast Tract Digestion IBS.

There are two basic approaches in treating the bacterial overgrowth itself. We talked about the first approach – killing or inhibiting the growth of the overgrowing bacteria using broad-spectrum antibiotics. The other approach is to limit the growth of overgrowing bacteria by minimizing the malabsorption of carbohydrates, the major fuel source for gut bacteria. The best way to accomplish this is with a diet that limits difficult-to-digest carbohydrates. When you remove the most difficult-to-digest carbohydrates from your diet, you have the almost magical ability to limit the growth of all intestinal bacteria, yeast, and other fungi across the board. Healthy gut bacteria are well adapted (because we evolved with these bacteria) to living in a nutrient-limited gut environment and will prevail over bad bacteria which are less well adapted to this environment.

There is one constant in SIBO, carbohydrate malabsorption, which feeds bacterial overgrowth. This issue must be addressed for lasting relief. Two basic types of diet can be used to limit carbohydrate malabsoption. One is an overall low carb diet (Heartburn cured) and the other is a selective diet that limits only the most difficult-to-digest carbs, (Fast Tract Diet described in the Fast Tract Digestion book series). For a full review on diets for SIBO, read my article on SIBO Diets and Digestive Health – It’s about Fermentable Carbohydrates.

Take home message

My recommendation is to treat all but the most severe forms of IBS with a science-based diet that limits SIBO. Antibiotics should be reserved for IBS/SIBO conditions that either fail to respond to diet or that involve more severe symptoms such as weight loss, failure to thrive, steatorrhea (the body’s failure to digest fats), anemia, bleeding or bruising, night blindness, bone pain and fractures, leaky gut syndrome, and autoimmune reactions, or in cases where SIBO has damaged intestinal villi (the hair-like projections in our small intestines which allow us to absorb nutrients). More severe symptoms which may include vomiting, constant diarrhea, fever or blood in the stool may be indicators of even more serious illness and should be evaluated by your doctor as soon as possible.

What do you think?

Disclaimer

I am a medical microbiologist, not a medical doctor or gastroenterologist. This article is presented for information only and should not take the place of discussions with your own doctor.

Though I have done my best to present this information objectively, I am the author of diet-based treatments for functional gastrointestinal disorders, SIBO and related conditions including acid reflux and IBS and provide individual consultation based on my 3 pillar approach:

- Dietary (including supplements)

- Behavioral

- Identifying and addressing underlying causes

References

[1] Attar A, Flourié B, Rambaud JC, Franchisseur C, Ruszniewski P, Bouhnik Y. Antibiotic efficacy in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-related chronic diarrhea: a crossover, randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 1999 Oct;117(4):794-7.

[2] de Boissieu D, Chaussain M, Badoual J, Raymond J, Dupont C. Small-bowel bacterial overgrowth in children with chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, or both. J Pediatr. 1996 Feb;128(2):203-7.

[3] Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3503-6.

[4] Scarpellini E, Giorgio V, Gabrielli M, Lauritano EC, Pantanella A, Fundarò C, Gasbarrini A. Prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in children with irritable bowel syndrome: a case-control study. J Pediatr. 2009 Sep;155(3):416-20.

[5] Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, Zakko S, Ringel Y, Yu J, Mareya SM, Shaw AL, Bortey E, Forbes WP; TARGET Study Group. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 6;364(1):22-32.

[6] Lauritano EC, Gabrielli M, Scarpellini E, Lupascu A, Novi M, Sottili S, Vitale G, Cesario V, Serricchio M, Cammarota G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth recurrence after antibiotic therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Aug;103(8):2031-5.

[7] Villarreal AA, Aberger FJ, Benrud R, Gundrum JD. Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the development of irritable bowel syndrome. WMJ. 2012 Feb;111(1):17-20.

[8] Hviid A, Svanström H, Frisch M. Antibiotic use and inflammatory bowel diseases in childhood. Gut. 2011 Jan;60(1):49-54. Epub 2010 Oct 21.

[10] Curry SR, Marsh JW, Shutt KA, Muto CA, O’Leary MM, Saul MI, Pasculle AW, Harrison LH. High frequency of rifampin resistance identified in an epidemic Clostridium difficile clone from a large teaching hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Feb 15;48(4):425-9.

[11] O’Connor JR, Galang MA, Sambol SP, Hecht DW, Vedantam G, Gerding DN, Johnson S. Rifampin and rifaximin resistance in clinical isolates of Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008 Aug;52(8):2813-7.

[12] Carman RJ, Boone JH, Grover H, Wickham KN, Chen L. In vivo selection of rifamycin resistant Clostridium difficile during rifaximin therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012 Aug 20. [Epub ahead of print].

[13] Liao CH, Ko WC, Lu JJ, Hsueh PR. Characterizations of clinical isolates of clostridium difficile by toxin genotypes and by susceptibility to 12 antimicrobial agents, including fidaxomicin (OPT-80) and rifaximin: a multicenter study in Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012 Jul;56(7):3943-9.

From my experience it doesn’t make much sense and from experience I would not regard medical sources as credible for this condition. I will only cite two cases but I could cite many more if required

1. Myself. From earliest memory a chronic heartburn reflux/sufferer who over the years employed the best that medical science could provide to no effect. This included tests for stomach bacteria, barium X-rays, acid remedies, etc. The diagnosis was always: structural defect. I accepted it until after 50 years the recommendation was for prescription proton pump inhibitors which I avoided based fortunately upon horse sense; who wants to increase the probability of stomach cancer. Fortunately in the same month a heart surgeon diagnosed heart arrhythmia. He was a rare case, when I asked why it had suddenly begun he gave the correct scientific answer, “I don’t know”. I took over using the engineering troubleshooting approach and in a couple of weeks found an association, and a week later cause and effect. The solution was dietary and permanent, least it has been for 15 years. However simultaneously with cause and effect being established the reflux resolved itself, also permanently. Think of this, lifetime form baby to age 55 and gone in a day. It doesn’t take a science degree to figure out an appropriate diet does it? one that starves out the bad little critters that have taken over usurping the ones that should be there.

2. My Wife. A trivial sufffereer of IBS for decades, she developed chronic permanent life-threatening IBS following a particular meal, in retrospect designed to encourage an overgrowth of hostile bacteria. Under the care of an excellent Doctor she endured every possible treatment, antibiotics, anti yeast and anti fungicidal drugs, MRIs, X-rays etc. to no effect. 18 months later she was 30 lbs lighter, down to 105 Lbs and falling, when the Doctor finally gave up and advised the only thing left was diet. She began eating what I did, recovered significantly in 24 hours and within a few weeks was back to her just married weight and has remained there for nearly ten years. Interestingly she had her serendipity too. The arthritis pain which was slowly twisting her finger simply went away and the fingers stopped getting any more bent; permanently.

There is a rule in science that of all possible causes for an observation the simplest is the most probable. It used to be called Occam’s Razor, more recently the Rule of Parsimony. Ignore it at your peril because if you do you may end up looking like a damn fool. Think of this what is your gut for? its for processing food; Food is its environment, intimately. The only food that gets into your body is what he gut allows to get in, the rest is eliminated. But what happens if its environment is so bad it is injured and can’t do its job properly? If you want to try an analogy go pee in the gas tank of your car and see what happens to it. Attempting a drug solution first not only breaks Occam’s, it probably won’t solve the problem because lack of antibiotics didn’t cause it. Its analogous to taking your car for a tuneup every week while continuing to pee in the gas tank. The only reason I can think of why anyone would suggest drugs as a first solution would be as an example of the saying “If the only thing you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. You want to know why I sound so truculent? try living with bad reflux for a lifetime, afraid to roll over in bed because you’ll have an attack while all the time you’re told its a medical condition and you are the medical equivalent of the nail. Then compound this with your wife’s suffering capped off with the $25.000 spent on unnecessary medical treatment and tests. Sure I’m truculent and loaded for bear. Don’t know what to do? read a book on heartburn, Norm has written a good one.

Sir

I am an indian native

Please suggest a diet .I have recovered using fibers from is diarrhea.but recently I shifted to a new city and again get trapped in ibs condition. I am a vegetarian. What food u suggest???

Hi Madhukar, Sorry to hear this. IBS is much common in people consuming only plants because they ferment in the gut via bacteria producing gas. I suggest you read Fast Tract Digestion IBS or get the Fast Tract Diet Mobile app and stick to the vegetables and starches with the lowest FP points. Also, read the trouble-shooting sections to make sure you are following the pro-digestion behaviors. You can consult with us via Skype if needed.

Hi Dave,

Thanks for relating yours and your wife’s personal experience with SIBO-related gut issues. I need to remember “Occam’s Razor”. Common sense is desperately needed in medical research today.

The problem with antibiotic resistance is not getting better which has the FDA worried. The article states:

“Research and development for new antibacterial drugs has been in decline in recent decades, and the number of new FDA-approved antibacterial drugs has been falling steadily since the 1980s. During this time, the persistent and sometimes indiscriminate use of existing antibacterial drugs worldwide has resulted in a decrease in the effectiveness of these drugs. This phenomenon, known as antibacterial drug resistance or antibiotic resistance, has become a serious issue of global concern.

More than 70 percent of the bacteria that cause hospital-associated infections (HAIs) are resistant to at least one type of antibacterial drug most commonly used to treat these infections. In the United States, nearly 2 million Americans developed HAIs in 2002, resulting in about 99,000 deaths.”

I hope the right hand talks to the left hand.

For the full article go to:

https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm320643.htm

Also, check out the FDAs’ article on antibiotic resistance.

https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ucm235649.htm

You only talk about one side of the equation. There is therapy that replaces the good bacteria after the you’ve killed the bad & the good with antibotics. It’s called fecal microbiota transplant therapy (FMT).

Hi,

Good point about FMT. The article is focused on antibiotics alone because they are increasingly being employed (without FMT) off label for IBS treatment. Also FDA approval is being sought for this treatment – without FMT.

FMT is a fascinating topic itself, but still in the experimental phase for C diff and there is even less experience using this approach with IBS. I agree, it may well emerge as an excellent therapy for IBS. For FMT, antibiotic pretreatment makes perfect sense. I do wonder if some people will relapse after FMT unless the issues that caused IBS in the first place are not addressed.

Yes, that is frightening that antibiotics are prescribed without a gut flora replacement plan – that’s what got us into this mess in the first place! I am soon to have FMT for a myriad of gut issues, so I am only just starting the journey. If it doesn’t work, then I might have to resort to helminth therapy….now that’s equally fascinating!

Good luck and please report back on your experience. There is a growing interest in the states on FMT for IBS but few doctors offer it and the costs are quite high.

It sounds so simple…just to give up carbs, but I’ve been doing it since 2009 and after so many years it starts to suck. However I don’t want to take antibiotics either because I feel like they caused my problems to start with. That and gallbladder removal surgery. I am down to where I cannot eat much at all. I have developed food allergies, and have all the same symptoms someone with celiac disease has. I can barely eat meat and have all sorts of health issues, thyroid, migraines..etc.

I was finally dx’d with sibo by the VA Hospital and they won’t even prescribe the antibiotics recommended by Pimentel, just a regular old antibiotic that kills everything including my stomach, which is the normal way they treat veterans, years behind on current medical treatments.

Hi Cheryl,

Sorry to hear it. Dealing with single issues are had enough, but when you add a couple of problems together (SIBO, antibiotics, gallbladder), coming up with a safe diet that offers variety can definitely be a challenge. One point: The Fast Tract Diet is not a “low carb” diet in a couple of different ways. Fermentation potential is limited, not carb amounts themselves. Also, some low carb foods (high fiber and sugar alcohols for instance) are subject to limits.

Please feel free to contact us if you would like to set up a counseling session.

How to heal SIBO permanently?

Thank you.

I am extremely happy to have happened upon this website while researching alternative treatment options for my SIBO. I was prescribed Rifaximin which is, as I type, waiting at the pharmacy for me to pick up. With all the bad press around antibiotics though, I am super hesitant to go there. But, I am also at my wits end with trying to determine what is causing my issues and living as a fraction of myself (i.e. always feeling sick). Through trial and error, I decided to eliminate dairy, wheat, and corn. While my symptoms are less frequent, they have not gone away entirely and I am still basically a prisoner in my own home, afraid of “getting sick” (as I call) it in public. This website has given me hope of correcting matters naturally in my gut. Thank you, thank you, thank you!

Happy to have you visit Coconut. You may want to share the Antibiotics for IBS article on this site or the FTD IBS book with your doctor and together decide if you should give a SIBO-focused diet a try before you take the antibiotic.

Dr. Robillard

I am a health educator and a GAPS pratitioner.

While I had heard of your book I has not had the chance to really read or understand much about your program.

I recently came across your site while doing research for a client struggling with some stubborn gut issues, and fatigue, after being on the SCD/GAPS protocol for close to a year.

She has made incredible progress on the diet, with a ton of healing that has occurred, but there are a few issues that just can’t seem to be resolved.

I am convinced of the basic tenets of the SCD program, but also know that as time and experience and science with regard to digestive health and microbiota improve , there is always more we can learn.

One thing that I have been thinking a lot about is the question of whether some forms of starch are needed (i.e. for persons following this protocol for any length of time presenting increases in muscle fatigue and overall low energy and mood) that are not included in these programs, what those starches should look like and what the long term affect of adding these starches could be.

In both Elaine and Dr. McBride’s research and clinical experience, they propose that often times the imbalance of gut bacteria doesn’t present clear identifiable gut issues, but greatly contributes to other wide range psychological and physiolgical illness, ie. autism, dyspraxia, heart disease, diabetes, autoimmune disease, etc, due to the toxicity of the gut.

MrBride in particular quotes Hippocrates , ” all disease begins in the gut”.

I have come to believe in the truth of this statement, supported by my own personal experience and also those of the many clients that I have had the privilege of working with on their journey towards healing.

I am very intrigued by your theory of FP, have ordered your book , and am anxious to learn more about your protocol and your research.

It may be that you address these questons in your book, as I have read your comparisons of the various approached , Paleo, SCD , Elemental etc. in your post of SIBO, which I felt was quite good.

This comparison spoke to the experience that I have had with some clients unable to tolerate most fruit and/or honey at the beginning of the diet,( which is legal on both GAPS and SCD like you mentioned) yet seemed to be able to add more of these in moderation as some of the healing progressed, but sometimes not.

Thanks for all that you are doing to help unravel a very complex and often individual specific problem for a lot of people , and one that definitely seems to be growing .

Hi Kt,

Thanks for sharing some great thoughts on diet and gut health as well as connections to psychological and general health. While I agree that some level of fermentable carbs is healthy for our gut and feeds our microbiota, there is a tendency in the West is to overfeed, not underfeed our microbiota. While the diet offers a different kind of safe starches (safe for symptom-free digestive health which is the opposite of other definitions of safe starch) for those that function better and remain healthy on higher starch diets, I personally feel less starch is better for our overall health especially as we get older. When you get the book, try a few calculations with the FP formula or scan the FP tables. You will see that there is much more fermentable material in our diet than we realize.

I’m in complete agreement in regards to the downsides of antibiotic overuse. However, having been a sufferer of diagnosed SIBO, and having tried all sorts of different strict diets and plans, I can tell you that the only thing that provided any relief whatsoever, and I mean at all, was xifaxan. Probiotics were very helpful in moderately controlling my symptoms early on, but soon became mostly useless. Ultimately, the only treatment that is likely to provide any sort of long term SIBO/ IBS relief is an initial treatment of xifaxan followed by a fecal transplant, periodic probiotic therapy and diet changes. Outside of that, any individual part of the treatment plan is simply an incomplete option. My two cents.

C, please I would like to see the evidence that fecal transplant impacts SMALL intestine bacterial overgrowth. My holistic doctor has not seen the transplants as being beneficial for SIBO unless all other predisposing factors that allowed the SIBO to occur to begin with are address. Fecal transplant does not appear to be a magic bullet.

PLEASE, I need urgent Help and advice! I just finished nearly two weeks on strong Amoxicillin to save my life. Now how do I save my guts?! I have always had severe stomach issues and have been gluten free and gaps and very low carb etc for years. I don’t procduce my own HCl, so have to take very high dose supplements as recomended by Dr Jonnathan Wright. I also take Glycine 2-3 times a day which REALLY helps more than anything else I’ve discovered over the years. But now I am really concerned about repopulation of my insides. I have been taking Biokult and Primal Defense during the course of antibiotics, and will continue to do so, but what else can I do to avoid dissaster?! Should I eat only eggs or something! I’ll do, or eat, or not eat anything to get this right. This is the first time I have found your site and so haven’t had a chance to read your books. Any advice Welcome! Thank you!

Hi Daphne,

Many people need to take antibiotics for serious illnesses. Gut microbes do repopulate over time and taking some probiotics and fermented foods may help. Given your concerns about diet you may want to read one of the Fast Tract books.

Dear Dr. Robillard,

I have been suffering with GERD since 2001. The issue was always the same — intense pressure in my stomach, on the left side under my ribcage, putting incredible pressure on my back, kidneys, etc — and also, heartburn. I never got on the PPI drugs; I just dealt with the pain. Otherwise, my health was fine, except for the awful monster known as GERD. Then I found your wonderful book, Heartburn Cured, and more recently, Fast Track Digestion. I had been enjoying almost complete relief from my symptoms for months and was counting my blessings.

However, several weeks ago, I unfortunately contracted a bladder infection and was given cipro, for eight days. It worked, with no problems. However, I then contracted bronchitis and was given a three day course of 500 mg of azithromycin. I immediately got heartburn from this drug. Unfortunately, I chose to ignore the heartburn and finished all three days. (It did get rid of the bronchitis.)

Now, for the first time in months, I have unrelenting stomach pressure and heartburn, as bad as anything I have ever experienced, even though I stick to the diet! Its been more than seven days and I have all the old horrors, in spades – pressure and heartburn. I have been taking Ultimate Flora Probiotic for the last three days. Have I damaged my digestive system to the point where I can’t get back to normal? How long will I have to wait before this wonderful diet works again? I feel so angry that I let my health slip away. Any advice for a believer who goofed up?

Hi Katie,

Most people need to take antibiotics at one time or another. Having taken two different types of antibiotics will have a more significant effect on gut bacteria. But over time, repopulation occurs. It’s impossible to know if there are other factors in your case without further discussions with you, but having symptoms despite being a low carb or low FP diet, suggest there might be. You should be under the care of a doctor just in case.

I recommend a holistic doctor in addition to the doctors that prescribed you the strongest antibiotic out there for a bladder infection. It is little known (but WELL known in the holistic world) that bladder infections (and bronchitis) can be treated with herbal antibiotics which are more forgiving of gut microbes than broad spectrum killers like CIPRO. As I type this, I wonder if people reading this realize how DIRE this is? Especially for women. The state of affairs for antibiotic therapy is such that the only effective medicines we have for urinary tract infections is CIPRO??? (and Bactrim and the like?) This is crazy! Also, your microbial imbalances that you had put you at risk for the UTI to begin with (and the bronchitis). Both are signs that your mucosa is dried out througout your body and is a fertile ground for microbial overgrowth. I learned that IBS/ bladder and sinus issues are ALL connected. I would consult with a good Functional medicine doctor, Natropath, or Classical Chinese Medicine doctor to look at all of your supplements and all of your organ systems that help with digestion. With your UTI history, did you or do you currently take NSAIDS or chemical birth control? All of these things affect gut flora too. A closer look and proper holistic support might be a good option for you, (in addition to Norm’s diet) it has changed my life.

Hi Dr. Robillard,

I’ve had gut problems for most of my life, and believe they were exacerbated by overuse of antibiotics due to strep (later realized I was eating too much sugar and simple carbs that made it worse). Took the breath test and was told my hydrogen and methane levels are both high, and the doctor wants me to take a high dose of rifaximin in combo with neomycin for 2 weeks. I’m eating a pretty strict diet now and taking raw garlic/grapefruit seed extract and it seems to significantly improve my health. What are your thoughts on doing both or just sticking to the diet and natural treatment? Any thoughts would be helpful and appreciated. The last thing I need (I have a one-year old and work full time) is to develop c-diff or something icky like that!

Hi Vanessa,

I feel for you having to go through this. I can’t offer individual advice here, but as stated in this article and other writings, I think people should first try a stringent low fermentable carb diet before reaching for antibiotics, except in cases of more severe symptoms or urgent health issues. In such cases, antibiotics may be required. Perhaps you could share this article with your doctor as you contemplate this decision.

Hi Dr Robillard,

I have had constant stomach pain for the better part of two years now and it’s ruining my life. I never have diarrhea or bathroom issues really just constant reflux, throat and stomach pain and slow gastric emptying. At first it was just minor reflux and I’ve been on some form of PPI for most the last decade but it seems to just get worse or at least my pain certainly is. There have been multiple ER trips on nights where I’m sure my stomach could kill me and the pain is unbelievable. This has led to severe health anxiety which of course doesnt help my constant nausea and pain issues. I may even be slipping into the world of fibromyalgia because it certainly seems like my internal nerve pain especially in my upper digestive tract is abnormal and idiopathic. I just last month had both scopes done at once and no ulcer was found though they did remove several polyps(this runs in my family). I’m constantly stressed by my pain I can barely run 2 miles without my stomach causing me so much pain I have to stop. I’m afraid to touch any alcohol, chocolate, or caffeine which is also making me miserable and I’m starting to feel like there is no answer and I’m losing hope. My best friend is a pharma rep and he gave me a course of Xifaxan and I’m very afraid to take them because of the many issues you stated above but he says that there is a good chance this will help with my motility issues. I want to believe in a miracle pill but I think I’m right to be skeptical. That said when you live like this every day you get desperate there are days when you think to yourself I cant live like this anymore not that I’m suicidal but my quality of life is so low right now and I have a 5 year old little girl who means the world to me so I’m trying to hang in there and she deserves to have a Daddy that isn’t so sick he can barely function some days. This has already cost me a job because of too many sick days and a relationship where the person accused me of being sick all the time as if I’m enjoying this lol. Anyways any thoughts or advice would be greatly appreciated and I’m definitely intrigued by your book though that said I’m skeptical of anyone who’s making money off of sick people no offense but there so many scams out there especially with reflux cures and the like. Thanks in advance and sorry for the long post!!!

Hi Chris, There’s nothing worse than prolonged symptoms such as those you describe. I can really empathize with you. I am happy to see you are taking some proactive steps with some advanced diagnostics to try and get to the bottom of your symptoms/condition. Please note from the comment I made above that I can’t give individual advice outside of our consultation program. but I can tell you my opinion is that remarkable improvements in GERD, IBS and many other conditions involving dietary malabsorption and disrupted gut microbes can be realized by most people by making dietary changes that limit carbohydrate malabsorption. I present the evidence in my books – not asking you to take my word for it. The Fast Tract Diet is not your typical trigger food diet limiting the usual culprits you mention – alcohol, chocolate, or caffeine etc., but rather focuses on the fermentation potential of foods.

As I discuss in this article, there are times when antibiotics make sense for the most severe forms of gut dysbiosis and SIBO, but I believe diet is the place to start. You might want to share the information in this article and in the book with your primary care or GI doctor to help determine if antibiotics are right for you or if you might want first try the Fast Tract Diet.

I know for sure that my gut problems were caused by massive doses of antibiotics [primarily fluoroquinolones which alter the DNA of bacteria at the point of replication] and am now allergic to most classes of these drugs.

I would like to let you know that there are about nine studies now showing that essential oils in specific combinations are proving to be even more effective against MRSA and SIBO than antibiotics & without the side effects. These remedies have been used for thousands of years but can’t be patented ;though some companies are altering the chemistry to do so [see Iberogast on Dr. OZ] so we are not hearing about this alternative.

I agree that diet is important but not the sole answer, nor are probiotics. I am now getting some relief from herbs while continuing to fight a staph infection [non MRSA] and if I cannot get SIBO to go away with this 3 pronged approach, I will pursue a fecal transplant. JAMA just yesterday published results of a a controlled study[ from Harvard] on the efficacy of fecal transplants on c difficile compared to antibiotics. Multiple rounds of AB were 30% successful and FT was 90% with 1 round, and they were monitored for a minimum of 8 weeks with no relapse. This was also done with enterically coated freeze dried fecal matter in pill form from extensively tested donors; not with surgery. There were no side effects either.

This will probably not be available soon [I have been reading about FT for several years now] and will still be pricey. I have read that this can be accomplished at home with fasting & deep enemas if you can find a willing healthy donor [test them first for HIV, HEP A, B C and parasites. ] who has not had antibiotics in a long time [or ever]. The last part is the hardest as even babies are given potent drugs these days. [there is a video on you tube telling how to do this.]

Hi CAWS, I agree herbal/oil-based antimicrobials are very interesting and have recently been shown at least in one study I read to be more effective than antibiotics. Fecal transplants given their success for C. diff infections may also be a great tool for functional gut disorders such as IBS. Routine use for IBS is still some time away given that clinical study for IBS is just beginning. As you indicated the DIY option is being considered by more people these days, but a good dose of caution is in order and screening of donor poop is critical to avoid infection by other pathogens. Also, if the underlying conditions (diet, motility, and the others I discuss in Fast Tract Digestion) which lead to microbiota imbalances in IBS or other functional gut disorders in the first place are not addressed, repeated treatments would likely be needed.

Thanks for your reply. I have a microbiology question for you. The donors in the Harvard study were screened for HIV, Hep A,B,C and parasites. I have never had chicken pox ; nor will I vaccinate for it because of the toxic adjuvants and two strains of aborted fetal cells in it. [www.cdc.gov -go to Vaccine media & Excipients 2013] Had the other childhood diseases in the 50s.

If I was to receive a transplant from a donor who had already had chicken pox immunity from the disease would I be at risk [ which at age 62 could be VERY bad] or would it give me antibodies? My husband is pretty healthy but has had both CP and shingles once so I am unsure about using him.

I feel my best option is to approach a “Weston Price ” family I know. Children are all home birthed, homeschooled, raised on a farm with organic food & raw goats milk & unvaccinated. All are smart & bursting with health. I am so in awe of this family & hope they will help if it becomes necessary to ask.

Mia you may want to find a WP chapter in your area and do the same.

Bearsmom: You are more right about the Cipro than you know. ALL classes of fluoroquinolones [Cipro, Levaquin, Avelox,Factive etc ] are actually chemo drugs. The makers brag that the reason they work so fast is because instead of destroying the bacteria’s cell lining or nucleus ; they ALTER the DNA of BACTERIA at the POINT of REPLICATION. Since it does not discriminate between good & bad bacteria; your ability to repopulate has been permanently compromised as YOU are now genetically modified. Fluorine added to the chemistry makes the drug go in longer, stronger, faster & deeper making it a cumulative poison . A microbiologist working for a university who was FLOXED [read the flox report for more info] was able to get access to advanced lab testing [blood] and they found FQ had adducted itself to all of his cells. These drugs were known to be toxic, but even though they are black boxed now as of 2008] for tendon rupture, pain ,permanent peripheral neuropathy and in court for delayed retinal detachment; they are still being prescribed [even to babies] for UTIs, sinus infections, & ear aches. We now have children presenting with FM/CFS–but nobody seems to know why?

There is another non fluorinated drug that also does this & is listed as a carcinogen but commonly prescribe for UTI: Flagyl [generic metronidazole]. More DNA altering drugs are coming on the market. I urge you all to read the “product package inserts” to reject all F drugs [list of 300+ at http://www.slweb.org ; click on FTRC link] and those that alter DNA. It is akin to radiation poisoning.

Hi, I was just wondering, would it be effective to take a course of antibiotics for the sibo and then follow that with the fast tract diet and lots of probiotics to rebuild? I’ve been prescribed Rifaximin and am thinking about just taking it to knock out the sibo all at once since I’m so tired of waking up choking on reflux and having trouble breathing. I’ve been trying the fast tract diet, but I mess up here and there. I guess I really need to knuckle down and be strict with it and follow the recipes given… I was just wondering what you think about combining antibiotics with the diet? Do you have a pro biotic that you recommend?

Also, what do you do about Christmas?? We are visiting my family this year and my mom makes so many wonderful desserts. Do I just keep myself from having any of it at all?? Ugh, that kinda makes me dread going since this stuff will be everywhere… How does one survive the holidays while fighting sibo? Thanks so much!

Our 9 year old son was diagnosed with a severe case of SIBO, he has to go to the hospital and get morphine. His doctor is starting him on the Cedar-Sinai protocol for IBS – we begin on Monday. He will be taking Rifaximin and Neomycin together, they are very safe antibiotics and are not systemic, they remain mostly in the bowel where they will perform their magic. After 5 years on very restrictive special diets like Gaps/SCD we are not convinced at all that diet alone can heal this condition. We are thrilled to start the protocol and lucky that we have a very open minded brilliant doctor.

I am so sorry for what you have been thru with your son & happy that you have a good doctor. Please don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater though. Diet & probiotic repopulation will also be critical after treatment. Show your doctor the Harvard study in JAMA on fecal transplants ;especially if Rifamixin gives him C-difficile.[see my post above]. While the pills in this study may not be currently available to the public ; if a healthy [tested for safety] donor can be found the patient can be endoscopically implanted by the gastroenterologist.

I am open to a fecal transplant, I’ve had them done myself actually (using a not so health donor) the problem is that it is VERY difficult to find a healthy donor these days. If I knew of a health donor I’d do one at home myself on our son, but I don’t know any healthy people. Everyone is sick these days sadly.

PS- Our son did the protocol and he is doing very well, he has completed it and we are doing another breath test this week to see if his SIBO is gone or not. If it’s not gone yet than we will need to do another 10 day round of Rifaximin and Neomycin, but if it’s gone than he will go on a prokinetic drug to get his motility working again (peristalsis drug). Wish us luck!!

Trying to find data on the use of these SIBO protocols for treating Anlylosing Spondilitis (AS) specifically (involvement of Klebsiella bacteria overgrowth), but I find absolutely nothing (basically just for IBS). I implemented a severely restricted low carb diet (almost no carb) since mid June, and it had a rapid and dramatic impact on my mobility and reduction in stiffness. However, even with the addition of garlic, probiotics, grape seed oil, digestive enzymes, etc. I am cannot seem to get off of the pain meds and a very low dose Prednisolone. Obviously I am considering the antibiotics along with possibly a motility agent. Does anyone please have any experience to share with treating AS using a SIBO protocol ?

I have a different SIBO-related health condition than you, but my limited understanding is that steroids and pain killers will seriously impede gut motility, so that is what I would try to address first, recognizing it would be a challenge to taper off completely. Also, garlic is a powerful antimicrobial and kills good and bad bacteria so I personally would not use that in my protocol. Also, Norm’s diet is not necesarily a low carb diet, it is a low fermentation diet, so it is possible that some of the foods in your low carb were still feeding the bacterial overgrowth? (This was the case for me!) I personally would look more closely at the Fast Track diet to see if there are any tweeks you could make to your current diet, and consider taking the leap of getting off the steroids and pain meds. My holistic doctor tries to get her patients of all these drugs as even though they can help manage symptoms, they may worsen the root cause of your condition which is dybiosis and SIBO? Sorry if that does not answer your question, but I would try the Fast Track approach before antibiotics, hands down, as the recurrence rate with abx treatment is horribly high.

Lynn, here’s info on how diet can heal that Ankylosing Spondylitis. Go to this website and scroll down to the title that says: Update: Attacking Ankylosing Spondylitis with PHD – also I have heard that AS is caused by a bacterial infection, so you may want to consider taking a low dose antibiotic for a few months, up to 1 full year.

Norm thank you for this great service you are providing. I will get your SIBO diet book from Amazon. Meanwhile a question: my first gastro doc put me on a FODMAP diet for SIBO. It sounds similar to what you recommend, non fermentable things, etc. What are the differences? (Aside from not being able to eat garlic, which is not FODMAP friendly!)

many thanks, DB

Note: FODMAP seemed to be working but in the end didn’t, second doc hammered my gut with 10 days of Neomycin/Xifaxan combo which is just finished and has only changed stool, not gas, etc….so far….

This article might help Dave.

https://digestivehealthinstitute.org/2012/08/17/sibo-diet-and-digestive-health/

Thank you so much Norm. I did get the book on Kindle and love it….One more quick question which others may also find useful: most diets for SIBO say don’t drink or eat milk products which aren’t lactose free. Yet many products which are lactose free are simply regular ones with lactase added. So if one takes half and half in tea with a lactase pill is that going to be OK? Or are there other sugars/carbs in there which the lactase does not neutralize and which might feed those nasty “bad” gut bacteria?

many thanks

DB

Hi David,

Lactase treated, lactose free milk is great as is taking lactase supplements before consuming milk or other lactose-containing foods. But milk and milk products also contain several oligosaccharides that behave as dietary fiber. Therefore, even lactose-free products will not have FPs of zero. As M alluded to, heavy (and light) cream have less lactose than milk.

Thank you Norm! You are great…..OK I will leave you in peace now to enjoy a wonderful Christmas and New Year, and as a fellow author, wish you much success with your so useful book…..

David

Why not just use full fat cream in coffee it gets around the lactose problem and taSte great!

Hi Norm,

I have been having symptoms of IBS for the last 3 or 4 weeks. I went to my doctor and having diverticulitis, he thought that my symptoms were caused by that and prescribed amoxicillin in case of a bacterial infection. I have started taking the amoxicillin and I am having second thoughts about continuing this treatment. I don’t want to contract s diff.. I am wondering if I should try taking a pro-biotic? What are your thoughts/opinion? Thank God I stumbled on to your site!!

Hi Rocky, I understand your concern. If it makes you feel any better, C. diff is a relatively uncommon occurrence. I would be happy to discuss your particular situation and alternative approaches within our consultation program.

Hi Norm. I have had ibs for years. Last week, I went on antibiotics for a sinus infection. I almost never take antibiotics. After a couple of days, my digestive system feels great. My stomach has not felt this good in years. I did some research about ibs and antibiotics and found your information. Today is the last day of the antibiotics. What can I do to keep feeling like this?

I am not surprised Donna. That was one of the early observations that led to the connection between SIBO and IBS – people feeling better after antibiotics for other issues. In our consultation program, we use several approaches to help people increase the diversity of their gut microbiota, particularly after antibiotics. It’s important not to relapse back into cycles of SIBO or dysbiosis. Fermentable carbs consumed in excess can once again feed blooms of gas-producing gut bacterial strains. Using the principles in the Fast Tract Digestion books or the new Fast Tract Diet mobile app will help. Varying your diet with many fresh herbs and low FP veggies will challenge your micribiota and increase the strain diversity.

Hi Norm. Thank you for your reply. I will definitely take your advice. I cannot believe what a difference the antibiotic makes. I forgot how good a normal gut feels. I do not want to go back to feeling lousy everyday.

Norm, I recently bought and read your book and commend you on the phenomenal effort you have put forth in this area of research. As a twenty-year sufferer of IBS/Sibo, what’s amazing for me is that your Fast Track diet almost exactly mirrors the diet I have developed for myself over the past twenty years to help reduce my own symptoms. In fact, drastically straying from the the diet causes flare-ups. During those flare-ups, I have been treated successfully with antibiotics. I am currently on Rifaximin for a flare-up which is working, and is directly in line with Dr. Mark Pimentel ground-breaking research and treatment plan. That, said, I wholeheartedly agree with you on the significant “cons” of antibiotics as they relate to long term efficacy, resistance, and side effects (I am now resistant to Metronidazol/Flagyl after taking five courses over the past twenty years). Natural treatment is simply a far better approach.

I mentioned earlier that my diet “almost” mirrors your Fast Track IBS diet. Without getting into the science too much, I can tell you unequivocally that the following foods have an extremely adverse effect on me – dairy that is rich in fat such as cream, very fatty red meats, deep fried foods of any kind, extremely spicy foods, and hard alcohol. As a result, I was shocked to read that heavy cream, fatty steaks/kielbasa/bacon, and hard alcohol all have extremely low Fermentation Potential (FP) scores. Also, your book does not mention the effects that deep fried foods or extreme spices may have on IBS/Sibo sufferers. Am I missing something here? I understand that we all have different biochemical makeups and my reactions to these foods may be specific to me. That said, I can assure you that you will find hundreds of thousands of other IBS/Sibo sufferers who have the same reaction to aforementioned trigger foods. There must be some sound scientific theory linking these foods to digestion issues. Again, I have been a guinea pig for twenty years who has done extremely well on your Fast Track diet except for when I strayed and except for when I consumed the following trigger foods – heavy creams, very fatty meats, deep fried foods of any kind, heavy spice, and hard alcohol. With all due respect to your research (I am a huge fan), I would love to get your thoughts on these specific trigger foods?

Hi Johah, Thanks for sharing your thoughts on the diet and other factors relating to IBS/SIBO. Given your repeated use of antibiotics followed by recurrence and in your own words resistance to at least one of those, I don’t think I need to comment further on the use of these drugs beyond what is stated in the article.

The FTD focuses on the dietary “elephant in the room” – hard to digest carbs. Of course, there are other things that can trigger intolerances. SIBO can lead to bile deconjugation that would contribute to fat malabsorption. But getting these bacteria under control by limiting the fermentable carbs they feed on is the FTD strategy to reduce bile deconjugation that is mediated by the overgrowth of bacteria. But other potential underlying conditions affecting bile (gallbladder issues, etc.) or even pancrease or pancreatic duct issues affecting release of the enzyme lipase may deserve attention as well. In the interim, I support your effort to moderate dietary fats if you are not digesting them well. Of course, when you take away fat calories, there are only so many protein calories you can use to replace them. This leads most people to over-consume carbs. That is a problem in my view.

Alcohol abuse can be a significant factor in SIBO and gut health, but moderate alcohol consumption according to my research is not the problem. I also discuss moderate alcohol not being a factor in the fourth part of my GERD series – GERD being another SIBO/IBS-linked condition.

In the same GERD article linked above, I have written / talked about deep fried foods. The biggest problem here for most people is not the fat, but the corn or wheat-based coatings that add too much resistant starch to the diet. And I know spice foods get lots of blame from people with GERD and related conditions. Here I think the biggest problem is irritation of the esophagus for GERD sufferers, and some spices (cinnamon, for instance) actually have higher FP points. The FTD mobile app lists the FP totals for a broad variety of spices and herbs.

Most importantly, I respect your efforts to get to the bottom of what foods are causing your own symptoms, by doing research and being aware of how you personally react to different foods. My comments are only meant to help in that evaluation.

I am suffering from excessive flatulence for almost five years and it is really annoying. I start to feel gassy from late afternoons but during the day I am comfortable and it is very rare. I don’t have any other symptoms like diarrhea or abdomen pain and nothing else just excessive gas which is really irritating.

My question is that having only excessive gas can be a symptom of SIBO, What other diseases can cause excessive gas other than SIBO and IBS?

I am 23 years and my weight is around 140lbs which has not increased or decrease during these five years.

Yes Ehsan it can, but so can excessive fermentation in the large intestine. Give the FTD a try. It will reduce the excessive fermentation and reduce the gas signficantly. If you need us, book a consult.

Wow I am so happy I typed in antibiotics and ibs. I had a tooth pulled out last week and was given amoxicillin. This is the second time I am reacting poorly and after 6 days I constant diarrhea, abdominal cramps and pain, sharp headaches, chills, fluid retention in my feet, body aches I went to the doctors who thought “appendicitis” and I walked out. Still crying from the pain and running to the bathroom.

I suffer from SLE with proven biopsy of Lupus Nephritis, very active Fibromyalgia, peripheral neuropathy to my motor and skin nerves, PCOS and now prediabetes. SLE became stable after four years of turmoil and living in the hospital but ibs has put me there so often as well I’ve lost count. So many times I was locked away in a single room bed with signs up on the door to basically cover yourself up from head to toe for possible C diff but was discharged a week later with no possible cause as to what happened. I had the same symptoms and boy was diarrhea consistent. I hate it.

My head is pounding now so I will stop thinking and typing now. I’m afraid I may be going to the ER tomorrow due to significant loss of fluid which I can’t seem to keep in me as it just exits and burns my rear end. Reading this has helped me to know what steps to take. I just pray that after 6 days of taking this and suffering like mad has not caused any more damage to my sensitive gut. Hard to know if he body pain is my fibro or not. I’m in pain everyday normally that I can’t tell the difference!

I hope this clears up faster than what I’ve been reading on other websites. ? I suffer enough chronically everyday.

Cheers

I hope you have a speedy recovery Monique.