Could one lowly bacterium, Prevotella copri, train the immune system to produce the type of human immune cell (Th17) responsible for inflammation and bone damage in arthritis?

According to a new study, also reported on in Wired, the answer could be yes. Based on some provocative early studies in mice, a team lead by Dan Littman, an Immunologist at New York University, found that the gut microbe Prevotella copri was present in the intestines of 75 percent of the patients they tested that suffered with untreated rheumatoid arthritis. The team also found that feeding mice P copri bacteria resulted in an increase in inflammation.

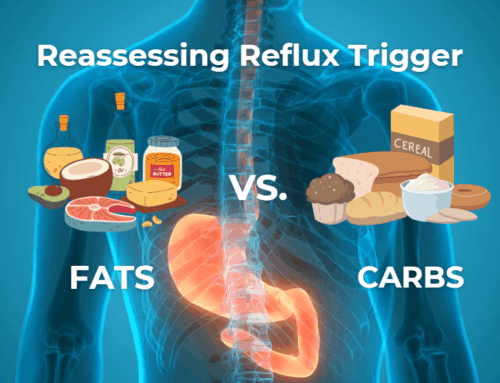

I found these results interesting in light of other recent studies suggesting that carbohydrate-based diets are associated with increases in Prevotella–enterotypes, while protein and satuated fat-based diets are associated with increases in Bacteroides enterotypes [1].

More studies are needed for sure (only 114 residents of New York were tested and some were healthy while others had a different type of arthritis) and having more Prevotella species in general doesn’t ensure that Prevotella copri will be present, but the idea that we need to consume lots of carbohydrates for a “healthy microbiome” freeing us of inflammatory / autoimmune diseases is one that also needs to be closely examined.

Here is a follow-up article on this topic that also pulls in Bacteroides fragilis as one of the good bacteria that may help prevent arthritis!

[1] Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R, Sinha R, Gilroy E, Gupta K, Baldassano R, Nessel L, Li H, Bushman FD, Lewis JD. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011 Oct 7;334(6052):105-8.

Norm,

In the second paragraph, did you mean to write:

“. . .the Bacteriodes species may be protective against inflammation”?

Thanks,

Mike

Hi Mike,

The article hints at this in this statement:

Thus, our data indicate that long-term diet is particularly strongly associated with enterotype partitioning. The dietary associations seen here parallel a recent study comparing European children, who eat a typical Western diet high in animal protein and fat, to children in Burkina Faso, who eat high-carbohydrate diets low in animal protein (13). The European microbiome was dominated by taxa typical of the Bacteroides enterotype, whereas the African microbiome was dominated by the Prevotella enterotype, the same pattern seen here. There are, of course, many differences between Europe and Burkina Faso that might influence the gut microbiome, but dietary differences provide an attractive potential explanation. Having confirmed enterotype partitioning and established the association with dietary patterns, it will be important to determine whether individuals with the Bacteroides enterotype have a higher incidence of diseases associated with a Western diet, and whether long-term dietary interventions can stably switch individuals to the Prevotella entero-type. If an enterotype is ultimately shown to be causally related to disease, then long-term dietary interventions may allow modulation of an individual’s enterotype to improve health.

I can’t remember off hand if I had a more direct reference than this inference about Western (inflammatory) disease prevention. My point was that we still have a lot to learn about the health benefits vs. detriments of particular bacterial strains in the gut. In the end, the answer will likely be “It depends”.