This is the transcript of the “How to Fix SIBO and Prevent Recurrence” video on YouTube. To watch it, click here.

Today’s topic is SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) and how to address it effectively to prevent recurrence. SIBO is a complex topic, and research is ongoing to improve diagnostics and treatment. But let’s talk about what we know so far.

What is SIBO?

Back in 1949, a man named Frazer described SIBO as fecal bacteria colonizing the small intestine and competing with the host for essential nutrients and perhaps winning. He was an expert on nutritional malabsorption, and his description is still relevant today.

SIBO is a form of dysbiosis involving an overgrowth of our native gut microbiota as opposed to an invading pathogen. Culture studies have identified several different bacterial species, some native to the small intestine and some migrating from the large bowel into the small intestine.

These include:

- Strep

- Escherichia coli

- Klebsiella

- Proteus

- Staph

- Micrococcus

- Lactobacillus

- Bacteroides

- Clostridia

- Veillonella

- Fusobacterium

- Peptostreptococcus

New research is trying to determine the most prominent bacterial strains in SIBO.

The Pimental lab, for instance, reported that E. coli, Aeromonas, and Klebsiella species are predominant.

On the other hand, a group of genomics researchers, Saffori and colleagues, suggested that a loss of S.I. diversity is more important for symptoms than SIBO itself. But one limitation in this study, potential skewing of their findings for SIBO is that they included patients with other diagnoses such as:

- Celiac disease

- Microscopic colitis

- Ulcerative colitis

- Pancreatic insufficiency

- Patients that underwent GI surgery

Regardless, the current prevailing view is that SIBO suffers have too many bacteria where they do not belong.

These bacteria produce proteases and other enzymes, gases, and toxic end products, causing symptoms and damaging the mucosal surface and villi. This damage can impact the ability to digest and absorb nutrients, minerals, and vitamins. The result is poor digestion which shunts nutrients to overgrowing bacteria causing a Vicious cycle of damage, malabsorption, and overgrowth, in the words of Elaine Gottschall.

SIBO is linked to many digestive disorders and other health issues, including:

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Esophagitis

- Crohn’s disease

- Diverticulitis

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Cirrhosis, Diabetes

- Fibromyalgia

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Asthma

- Rosacea

- Restless legs syndrome

- Interstitial cystitis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Parkinson’s disease

- Heart disease

- Autoimmune conditions including celiac disease, Hashimoto’s, scleroderma, and type 1 diabetes

The list continues to grow.

The exact number of SIBO suffers is unknown. But it is likely well over 100 million people in the US alone, given the number of conditions linked to SIBO.

What are the symptoms of SIBO?

SIBO symptoms may include:

- Gas

- Bloating

- Distension

- Flatulence

- Abdominal pain

- Cramps

- Acid reflux

- Diarrhea

- Nausea

- Dehydration

- Fatigue

- Brain fog

- Skin conditions

Constipation is another common symptom that often occurs in concert with intestinal methanogen overgrowth, IMO most notably Methanobrevibacter smithii.

More severe symptoms of SIBO may include:

- Weight loss

- Failure to thrive

- Steatorrhea (fat malabsorption)

- Anemia

- Bleeding or bruising

- Night blindness

- Bone pain and fractures

- Leaky gut syndrome

- Autoimmune reactions

These symptoms are not surprising because SIBO occurs in the small intestine. The mucosal surface of the small intestine is sensitive to damage that not only impacts digestion but also impacts its barrier function.

Leaky gut allows undigested food particles, bacterial antigens, and toxins to enter the systemic circulation. Leaky gut coupled with molecular mimicry is considered a hallmark of autoimmunity.

How to diagnose SIBO?

There are only 2 methods at this time. One is breath testing, and the other is culturing bacteria from the small intestine, which is considered the gold standard. But neither test is truly a gold standard.

Each method has drawbacks and limitations.

Eventually, better methods for sampling the small intestine, coupled with advanced genomic testing of bacterial populations, will prove superior. But we’re not there yet.

Right now, non-invasive breath testing is most commonly used for diagnosing SIBO.

Breath testing is based on the idea that excess bacteria in the small intestine can ferment sugars and produce unique gases. These include hydrogen, which can be further metabolized into hydrogen sulfide and methane in the case of sulfate-reducing bacteria and Archaea organisms, respectively.

These gases diffuse into the bloodstream and are exhaled through the lungs. Generally speaking, you know these gases come from your gut microbes because other than tiny amounts of H2S, none of these gases is produced by humans.

2 types of breath testing are routinely used for SIBO. One uses lactulose, a type of non-digestible sugar as the fermentable substrate, and the other uses glucose, another type of fermentable sugar.

I recommend lactulose breath testing, which is less specific for SIBO (more false positives) but is more sensitive, detecting SIBO throughout the lengths of the small intestine. The problem with glucose is that it’s rapidly absorbed in the early part of the small intestine, so it can’t detect SIBO in the lower part of the small intestine very well.

Most breath tests measure 2 gases, hydrogen, and methane. Hydrogen is linked to diarrhea, while methane (produced by Archaea organisms) is linked to constipation.

The newest breath test called Trio-Smart measures 3 gases:

- Hydrogen

- Methane

- Hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a gas produced by sulfate-reducing bacteria such as:

- Desulfovibrio

- Desulfobacter

- Desulfobulbus

- Bilophila

- Pseudomonas

- Citrobacter

- Aeromonas and several others

At normal levels, hydrogen sulfide is a beneficial anti-inflammatory gasotransmitter or signaling molecule contributing to physiological health, but excessive amounts have been linked to:

- Diarrhea

- Possibly constipation

- Genotoxicity

- Inflammation

- Altered mucosal integrity

Challenges with breath testing still remain. For example, rapid transit (how quickly food [sugar in this case] moves through the small intestine) may give false positive results if the lactulose moves too quickly through the small intestine and ends up measuring colonic fermentation instead of SIBO.

Also, there is a question about the ability of breath testing to diagnose SIBO when very few bacteria are present accurately. As little as 103, 1000 bacteria/mL is positive for SIBO. Can such a small number of bacteria produce measurable amounts of these gases?

Also, keep in mind that SIBO is only one of several forms of dysbiosis. Therefore, being SIBO negative does not exclude the possibility of other forms of dysbiosis, including small intestinal fungal overgrowth (SIFO), intestinal methanogen overgrowth (IMO), large intestinal bacterial overgrowth (LIBO) which occurs in the first part of the large bowel, or significant imbalances in individual species (generalized dysbiosis) that could be the cause of your symptoms.

What are the treatment options for SIBO?

Antibiotics

The most common treatment is antibiotics, a class of drugs I researched and developed while in pharma.

The top two antibiotics for SIBO are rifaximin approved for IBS-d to address hydrogen-producing bacteria and a combination of rifaximin and neomycin for constipation to address IMO, intestinal methanogen overgrowth.

It’s reasonable to think that SIBO is an “infection” and, therefore, something that needs to be killed. Antibiotic treatment is based on this notion. But we should keep in mind that SIBO arises primarily from bacteria in our own large and small intestines. These bacteria are part of our commensal population.

They play important roles in:

- Nutrition

- Immunity

- Bile acid levels

- Appetite

- Fat storage

- Protection from true pathogens

So, keeping them contained in balance in the right place, instead of killing them, seems like the best strategy.

Also, we don’t want to kill off indigenous small intestinal, bile-tolerant bacteria that have an essential role in digestion and health.

Antibiotics can be useful when your symptoms are severe

For instance, if you become malnourished, experience significant weight loss and/or other severe symptoms, or have SIBO-related health issues.

Antibiotics won’t work in all cases but will often reduce the overgrowth, improve symptoms, and help restore small bowel function. Unfortunately, antibiotics do not address the underlying causes; without that, SIBO, IMO, and other forms of dysbiosis will likely come back.

So, with or without antibiotics, the underlying cause piece must be part of the overall treatment strategy for SIBO.

Another challenge with antibiotics is that they are not as effective as you might think

Many intestinal bacteria are highly resistant to antibiotics or quickly become resistant. Regarding rifaximin, a 2016 study showed that 68% of SIBO-related IBS-d patients required the second retreatment. And some in the group were retreated up to 5 times.

Another study looking at retreatment found that the efficacy of retreatment was also questionable. It was only 33% successful vs. 25% with placebo.

At least rifaximin is one of the safer antibiotics because it stays mostly in the intestine minimizing systemic reactions. And the same is true for neomycin.

Moving to more potent systemic antibiotics increases the risk of side effects, C. diff infection, allergic reactions, and bacterial resistance, which renders antibiotics less effective for fighting serious infections in the future.

How about herbal antimicrobials?

Many herbal extracts are known to possess antimicrobial activity based on testing in the lab, but this activity has not been confirmed in well-controlled human trials. Also, individual herbal extracts tend to be less potent than synthetic antibiotics.

That is why they are often used in combination, including:

- Allicin

- Berberine

- Oregano oil

- Neem

While a variety of these extracts have been proposed for SIBO treatments, there is not much published data on the efficacy.

A small study in 2014 found that a combination of herbal antibiotics was at least as effective as rifaximin. But we need more definitive studies to confirm these results. Also, keep in mind that rifaximin was only 10% better than a placebo in the study used to get FDA approval.

Probiotics

You may have heard that SIBO patients should not take probiotics because “why would you add more bacteria when you already have an overgrowth?” While probiotics are not a panacea, some may be helpful based on studies.

Here are a few that come to mind:

- In a 2016 study, a combination of Bifidobacteria bifidus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Streptococcus faecalis in GI cancer patients with SIBO showed that SIBO was resolved in 81% in the treatment group, compared to 25% in the placebo group.

- In a 2014 study, a probiotic containing below resolved SIBO in 24% of liver disease patients in the treatment group but none in the control group.

- Bifidobacterium bifidum

- Bifidobacterium lactis

- Bifidobacterium longum

- Lactobacillus acidophilus

- Lactobacillus rhamnosus

- Streptococcus thermophilus

- A 2020 study of Saccharomyces boulardii and the antibiotic metronidazole given alone or together to systemic sclerosis patients for 2 months showed that boulardii resolved SIBO in 33% of patients compared to metronidazole which resolved SIBO in 25% of patients. Together the results were additive which might suggest each works by a different mechanism.

- A 2009 study reported on 40 SIBO patients with diarrhea and other symptoms that were given Bacillus clausii for 1 month. They reported a 47% SIBO eradication rate. Keep in mind that this was a “letter to the editor”, not a full-blown publication, so the details were limited.

- A study on 20 patients with constipation and IMO (previously referred to as methane dominant SIBO) showed that Lactobacillus reuteri given for 4 weeks significantly improved weekly BMs and reduced methane levels.

Note: While probiotics can be helpful, some people may experience symptoms such as loose stools, bloating, or abdominal pain, particularly when they start taking them.

Other dietary supplements

Various dietary supplements are promoted for treating SIBO, and some can be quite helpful.

Here are some examples:

- A multivitamin with minerals to address nutritional deficiencies

- Digestive enzymes with or without bile salts to improve digestion (improved digestion limits fuel for SIBO bacteria) and bile has antimicrobial properties

- Betaine HCl and sublingual B12 if you have low stomach acid (see my video “Are you at risk for low stomach acid”)

- L-glutamine, N-Acetyl glucosamine, zinc carnosine, and N-acetyl cysteine to support mucosal lining and integrity.

- Anti-biofilm agents

Anti-biofilm agents are included in the herbal treatment study I mentioned. These supplements are mostly enzymes that are effective at disrupting biofilms in the lab, but there is limited data to show they work in patients.

It’s true that most of our microbes (in fact, most microbes on the planet) exist as biofilms, but most of those are healthy biofilms, so disrupting biofilms in the gut is questionable. I can see this for invasive biofilms like what can occur with colon cancer, but for biofilms on the mucosal surface, our body is capable of sluffing these off if needed.

For more information about dietary supplements, see my article, “Dietary Supplements – Helping or Hurting Your Digestive Health?”

5 things to keep in mind when taking supplements:

- Check to make sure that you are not taking toxic levels of certain vitamins or minerals (A, D, E, B6, zinc, iron, and calcium, for example)

- Consider that some supplements can impact other medications you might be taking

- Make sure they don’t contain excess carbohydrates, which can further fuel SIBO – read the labels.

- Most supplements are meant to be taken for a period of weeks to a couple of months. Long-term use may carry health risks.

- Always check the labels and read up on possible side effects and health risks before taking them.

Again, supplements can be quite helpful when used judiciously, but over-supplementation is common. And unfortunately, it can complicate things in the treatment of SIBO. Therefore, I am very careful when evaluating and recommending specific supplements to my clients as part of my consultation process.

Diet

Last but not least, your diet and dietary behaviors are two of the most important factors, along with identifying and addressing underlying causes.

The pervasive view on diets for SIBO is that “SIBO diets only address the symptoms.” But the symptoms are not just floating out in space; they are being caused by something. A few years ago, I gave a talk at SIBOCON focused on this point. For more information, watch my presentation.

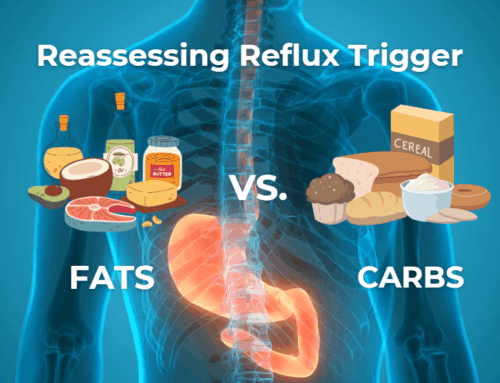

My conclusion was that diets that limit specific carbs or overall carbs are effective at resolving symptoms. They also reduce intestinal gases and short-chain fatty acids, restore pH balance, and address dysbioses in IBS, obesity, and epilepsy, all SIBO-linked conditions.

And views on science-based diets are changing. For instance, “91% of 1,500 gastroenterologists believe that diets are as good or better than medical therapies for IBS,” based on a survey conducted in 2018.

Carbohydrate intolerance

In the past, many of the symptoms we now associate with SIBO were recognized as carbohydrate intolerance. Sound familiar?

This is important because carbohydrate intolerance is a form of malabsorption that can lead to dysbiosis and help feed SIBO. For instance, lactose intolerance is very common in SIBO patients and has been recognized for over a century, while fructose intolerance which is also linked to SIBO, was first documented in the 1970s.

Recently, sugar alcohols (except erythritol) and dietary fiber intolerance have been added to the list. And I make a case in the Fast Tract Digestion books that resistant starch is related to dietary fiber and should also be limited for SIBO and other conditions involving carbohydrate intolerance.

According to the Merck Manual, the standard treatment for carbohydrate intolerance is to limit the offending carbohydrate species.

This simple conclusion is supported by the Textbook of Primary and Acute Care Medicine, which states, “Dietary alterations to reduce intestinal gas, a hallmark of SIBO, require the elimination of:

- Lactose

- Fructose

- Certain oligosaccharides

- Resistant starch

- Fiber

- Sugar alcohols

This is precisely the group of carbohydrates that the Fast Tract Diet targets.

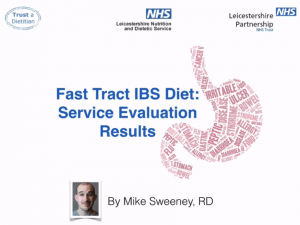

The very same dietary recommendations for IBS are also found in the NICE European guidelines based on Cochrane reviews and other published literature. In addition, Mike Sweeney, a dietitian in the UK, and his colleagues used the Fast Tract Diet for their IBS patients and reported its effectiveness in his service evaluation.

There is also a pilot study (still in the pre-print stage) demonstrating the efficacy of the carnivore diet in resolving SIBO. Finally, the elemental diet, which eliminates all complex carbs, is quite effective at addressing SIBO.

Regardless of whether you take synthetic antibiotics or antimicrobial herbs, a diet that limits fermentable carbohydrates is required for addressing SIBO. And once your symptoms are fully resolved, you can experiment with reintroducing certain carbohydrate species slowly and safely as your digestion improves.

To put it all together

All 4 elements I talked about can play a role in addressing SIBO For serious cases of SIBO with nutritional deficiencies, antibiotics may be recommended, but for fully addressing SIBO and for preventing recurrence, there are three key elements that cannot be ignored:

1 Do everything you can to identify and address the underlying cause(s)

Underlying causes will vary from person to person, and there are at least 25-30 possible underlying causes. A chapter in the Fast Tract Digestion books will be helpful on this topic.

Some examples include:

- Pancreatic insufficiency

- Antibiotics

- Bile acid issues (too much, too little, excessive deconjugation by bacteria, poor reabsorption, etc.)

- Brush border enzyme deficiency or villus damage

- Low stomach acid

- Anything that alters motility (including GI infection, medications, excessive methane levels, scleroderma, surgery, adhesions, diabetes, etc.) and more

2 Limit fermentable carbohydrates in your diet

The full spectrum of fermentable carbs includes:

- Lactose

- Fructose

- Resistant starch

- Fibers

- Sugar alcohols (other than erythritol)

You want to match your diet with your ability to digest and absorb nutrients, particularly carbohydrates. SIBO bacteria depend on carbohydrates as their primary fuel source, either directly or the downstream byproducts of fermentation. For instance, Methanogens and SRB use the hydrogen produced from primary fermenters.

3 Incorporate pro-digestion, pro-absorption behaviors, and practices

This area is often overlooked but plays a critical role in addressing SIBO and other forms of dysbiosis.

- How are you selecting your foods?

- How are you preparing and storing them?

- How are you consuming them?

- Do you leave spaces between your meals?

- Do you ever fast? If so, what is your approach to breaking fasts?

- What dietary supplements have you tried aimed at improving digestion?

Each of these three elements is a feature of the Fast Tract Diet.

Next step

For more information about the Fast Tract Diet system, you can read the Fast Tract Digestion IBS book and use the Fast Tract Diet mobile app to implement the diet.

For questions and support, you can join the Fast Tract Diet Facebook group, and for individual consultation, you can contact me through our contact form or by calling at (844) 495-1151 (US).

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.