This is the second article of a four-part series on acid reflux and GERD. Read the first article on the underlying cause, the third article on the mainstream medical treatments, and the final article on the myths of trigger foods and the GERD diet that works without drugs.

Does H. pylori cause GERD?

Based on my review, H. pylori is not a common cause of acid reflux but may contribute to atypical non-acid reflux symptoms in some people.

I wrote about my own struggles with GERD in my first article and how I was able to control symptoms by modulating dietary carbohydrates. Some years later, I learned that I was infected with H. pylori. I was treated for the infection, but there was no change in my susceptibility to acid reflux following treatment. My symptoms, though completely under dietary control, gradually reemerge when I consume too many carbohydrates over a period of 3-5 days, particularly those that are difficult to digest and absorb. Of course, my experience may not be typical of others with acid reflux and H. pylori. So, let’s take a closer look at this connection.

H. Pylori is a type of bacteria that has adapted through evolution to life in the stomach of approximately two-thirds of all humans, though eradication efforts are making progress against this bacteria at least in developed countries. To survive in the stomach, the bacteria swim through mucous that lines the stomach by using multiple flagella, rotating hair-like appendages that provide locomotion. When H. pylori bacteria reach the stomach wall, they attach and begin secreting an enzyme called urease, which converts urea to ammonia. The ammonia reduces the stomach acidity where the H. pylori is attached allowing this bacteria to survive and multiply. The biggest risks for people infected with H. pylori are stomach ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and stomach (gastric) cancer.

Studies on H. pylori and GERD

One study found that GERD patients were more likely to harbor H. pylori than non-GERD patients.[1] However, they did not find the same correlation in people with GERD who also had IBS. This makes little sense to me and casts some doubt on the validity of the findings.

On the other hand, numerous other studies have found that people harboring H. pylori are actually less likely to have GERD, including esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus, two serious conditions arising from severe and chronic GERD. I will break down the studies into:

- GERD patients who had H. pylori but were treated for the infection.

- GERD patients with H. pylori infection compared to the same population without.

Studies on GERD patients where H. pylori was eradicated with antibiotics:

- H. pylori eradication had no impact on esophageal acid exposure or LES (lower esophageal sphincter) pressure.[2]

- H. pylori eradication resulted in no consistent change in gastroesophageal acid reflux.[3]

- No differences were detected in acid reflux before and after H. pylori eradication.[4]

- Eradicating H. pylori increased (not decreased) esophageal acid exposure and in some cases, worsened reflux symptoms.[5]

Conclusion 1:

Successful treatment of H. pylori infection does not improve GERD symptoms, esophageal acid exposure, LES pressure changes, or acid reflux. In some cases eradication actually made things worse.

Studies on GERD patients with H. pylori infection compared to the same population without:

- The rate of H. pylori infection is lower in GERD patients compared to the general population. The absence of H. pylori is associated with more severe GERD. The results indicate a protective role of H. pylori against GERD.[6]

- H. pylori infection is inversely associated (protective) with GERD and GERD symptoms.[7]

- The H. pylori infection rate was lower in individuals with acid reflux compared to controls.[8]

- H. pylori infection was inversely associated with the risk and severity of reflux esophagitis, suggesting the organism may have a protective role against GERD.[9]

- H. pylori infection is associated with a lower risk of GERD.[10]

- H. pylori-negative patients had more severe esophagitis and were more likely to have Barrett’s esophagus.[11]

- H. pylori infection was inversely associated (protective) with Barrett’s esophagus and GERD symptoms were not associated with H. pylori infection.[12]

Conclusion 2:

H. pylori infection is less common in patients with GERD, esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus. H. pylori infection is associated with less severe GERD symptoms and may have a protective role in GERD.

If H. pylori was a causative agent in GERD, one would expect that any decrease in H. pylori infection rates would also reduce the incidence of GERD, but the opposite is actually the case. As the worldwide incidence of GERD is increasing, infection rates of H. pylori are decreasing.[13] And as hospitalization rates have decreased for gastric and duodenal ulcers and gastric cancer, presumably due to H. pylori infection, hospitalization rates due to GERD and esophageal cancer, have risen significantly.[14]

Additional studies suggest that certain strains of H. pylori (cagA+) may actually be protective for people with more severe forms of GERD.[15],[16]

Based on my review of the published literature and my own observations lead me to believe that H. pylori is not a causative factor in GERD in most people, and some strains of H. pylori may actually be protective for GERD. I will address H pylori’s role in non-acid reflux below.

Does low stomach acid cause GERD?

Another notion popularized in the book “Why Stomach Acid Is Good For You” by Jonathan Wright suggests that GERD might actually be caused by too little stomach acid. Hypochlorhydria and achlorhydria refer to having low stomach acid or no stomach acid, respectively.

The most common cause of low stomach acid is acid-reducing drugs, including antacids, H2 blockers, and proton pump inhibitors. The second most common cause of low (or no) stomach acid is chronic inflammation of the stomach referred to as chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG). CAG is often due to long-term infection with H. pylori, especially when PPI drugs are taken at the same time.[17] Much less frequently, CAG results from an autoimmune condition where our immune system attacks acid-producing stomach parietal cells. Low (or no) stomach acid can also be caused by surgery affecting acid or gastrin-producing cells, other (non H2 blocker or PPI) drugs that affect stomach acid production, stomach cancer, or hormonal disorders.

Low stomach acid – especially if caused by CAG can have profound negative health effects, including:

- Increased long term risk of stomach cancer and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

- Diminished vitamin B12 absorption (risk of anemia) and likely other vitamins.

- Diminished mineral absorption including calcium (risk of bone fractures), magnesium (risk of serious cardiovascular, neurological problems and also bone health) and iron (risk of anemia)

- Increased risk of bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine and stomach since stomach acid is part of our bacterial control system

- Increased risk of C diff and other GI infections likely because our acid barrier to outside pathogens is missing

While low stomach acid has many harmful health effects, can this condition cause symptomatic GERD? I had the opportunity to put this question to Dr. John Pandolfino, Chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.[18] His answer encompassed the role of H. pylori in the loss of stomach acid:

“The rule of thumb has been that H. pylori is protective of GERD if it is body predominant and reduces acid (Infection with H. pylori in other parts of the stomach, the antrum, for example, can lead to increased stomach acid, but this is less common)[i]. This has been shown in regard to risk of esophageal cancer, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophagitis – all are lower in patients with H. pylori and low acid. You certainly would not increase acid production to improve GERD.”

Dr. Pandolfino’s explanation is consistent with studies I have reviewed, including one well-controlled study that looked at 155 patients with esophagitis, where acid reflux is severe enough to inflame the esophagus.[19] The authors found no differences in gastric acid or pepsin secretion and concluded that “factors other than amount or composition of gastric juice per se must be responsible for susceptibility to esophagitis.”

Another study found that subjects with a particular type of gastritis called “corpus (or body) gastritis”, a form of chronic atrophic gastritis or CAG known to result in reduced stomach acid, had a 54% reduced risk for reflux esophagitis.[20] Two Japanese studies support the conclusion that CAG is protective for GERD.[21], [22] Finally, two large German studies that looked at 9444 and 8936 older adults respectively, found a strong inverse association of CAG with heartburn.[23], [24]

I found additional information on stomach acid levels in GERD patients in a study done to support the new drug application (NDA) for the PPI, lansoprazole, with 60 juvenile GERD patients. They conducted 24-hour intragastric pH levels (stomach acidity) and found GERD patients had the same pH levels as healthy adults, meaning they did not have low acid levels.

A study where increasingly acidic solutions were infused directly into people’s esophagus showed that more acidic solutions (less than pH 4) triggered greater GERD symptoms.[25]

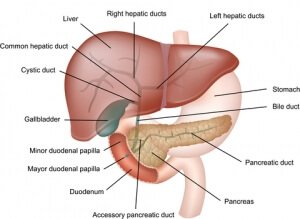

Also, recall from our previous discussion that 80% of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients have acid reflux. There is evidence that these patients produce normal amounts of stomach acid.[26] But we know for a fact that mucus often clogs their pancreatic ducts; therefore, they are unable to release sufficient amounts of digestive enzymes. This results in well-documented carbohydrate malabsorption and SIBO,[27],[28] which I believe without question is the underlying cause of acid reflux in CF.

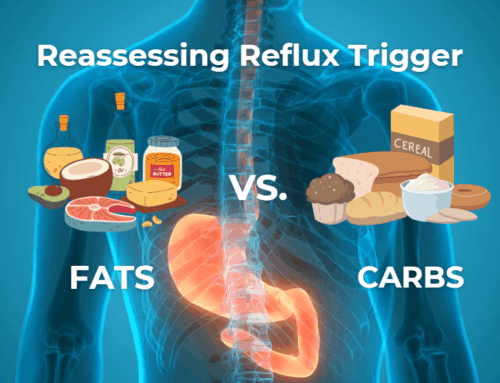

Finally, the success of carbohydrate-restricted diets for treating GERD symptoms[29] supports the published findings above, simply because carbohydrate-restriction works without any manipulation of stomach acidity.

The quick action of antacids in quelling heartburn symptoms in most people attests to the importance of stomach acid in reflux symptoms. People with heartburn who regularly take bicarbonate understand that they can feel the gas forming from the baking soda and acid reacting, followed by a burp of relief. You can easily test this yourself whenever you have a bout of heartburn.[ii] Just take some Tums or baking soda and see if you feel better. If you do, low acid is likely not your problem!

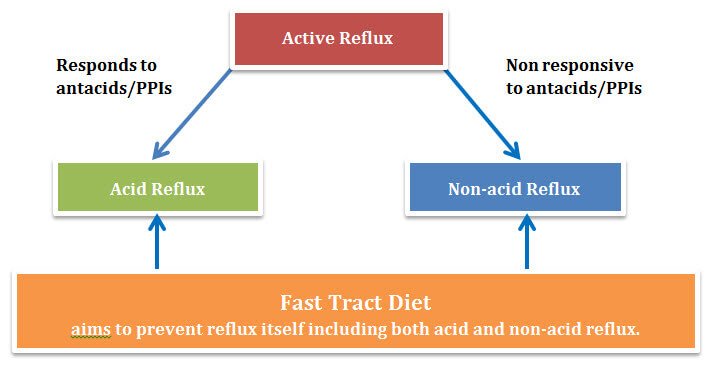

What about Non-acid or “Bile” Reflux?

While low stomach acid may not provoke as many typical GERD symptoms (which are likely more dependent on the acid component), it might be expected to lead to more episodes of “non-acid” reflux. In fact, there are reports of symptomatic reflux in people who lack stomach acid. One case report used something called impedance monitoring, which can tell the difference between acid reflux and non-acid reflux, to document a case of non-acid reflux in an individual with confirmed achlorhydria.[30] In this case, the 72 year old woman was H. pylori negative, but was diagnosed with autoimmune atrophic gastritis and had undergone gallbladder removal.

A larger study that examined both “acid” and “non-acid” reflux in GERD patients taking PPI drugs (they have low stomach acid by definition) found that about half of the participants registered positive symptoms scores, of which 11 % were due to acid reflux, while 37% were due to non-acid reflux.[31]

While typical GERD symptoms are more common in people who produce normal levels of stomach acid, people with low stomach acid (mostly, these are people taking PPIs but also some with CAG) can also suffer from symptomatic non-acid reflux. Potential triggers for non-acid reflux include caustic bile salts, which are normally produced to help digest fats, and digestive enzymes, particularly pepsin. Bile salts have been linked to heartburn symptoms in at least one study.[32]

From my review, I conclude that classic GERD symptoms are more dependent on the presence, not the absence, of stomach acid, but symptomatic non-acid reflux can occur in people with low stomach acid – most of whom are taking PPI drugs.

Given the number of serious consequences from having insufficient levels of stomach acid and the observations (though limited) of symptomatic reflux in a subset of people with low stomach acid, anyone who suspects they have low stomach acid should be tested. People who are on acid-reducing drugs don’t need to be tested. That’s what these drugs do – reduce stomach acid.

If low stomach acid is confirmed, the underlying cause of the condition (PPIs, H. pylori-mediated or autoimmune-mediated gastritis, etc.) should be addressed wherever possible. Betaine HCl may help, but check with your doctor and proceed with caution because too much stomach acid can irritate or burn your stomach lining or even cause an ulcer over time. The risk is much higher for people taking NSAIDs.

Summing it up

1. H. pylori infection is NOT linked to GERD, and some strains of H. pylori may be protective against GERD.

2. People with low stomach acid have fewer GERD symptoms and are less likely to have esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus.

3. Most people with GERD have normal amounts of stomach acid.

4. Low stomach acid induced by PPI use, H. pylori, or other causes, while not a cause of acid reflux, may result in symptomatic non-acid reflux in some people as well as a host of other problems.

Recommended action

Because stomach acid and other components of reflux (i.e., bile and pepsin) can trigger symptoms, it’s critical to stop the reflux itself. The Fast Tract Diet strategy will help control both acid and non-acid reflux by limiting fermentable carbohydrates that allow gut microbes to produce gas, leading to gas pressure and reflux.

If you believe you have low stomach acid (based on the “antacid test”) and may be suffering from non-acid reflux, it’s important to identify and address the causes, such as PPI, H2 blocker medicine usage, chronic atrophic gastritis or other causes discussed in this article and my book. Talk to your doctor about the Heidelberg acid test, which will confirm if you suffer from this condition before taking betaine supplements.

What’s next?

The third article, “GERD – Why standard treatments are ineffective”, of this blog series reviews the pitfalls of current therapies.

Read the first article, “What Really Causes Acid Reflux and GERD?”

Read the final article, “GERD diet that works without drugs”

Foot Notes:

[i] The effect of H. pylori on stomach acid is a bit complex, but there are three basic types of H. pylori infection, each affecting stomach acid levels differently:- Body-predominant (more common) where H. pylori infection occurs in the middle or “body” of the stomach, often leading to low stomach acid secretion and a higher risk of stomach (gastric) cancer.

- Antral-predominant (less common) where H. pylori infection occurs in the lower part of the stomach often leads to increased stomach acid secretion and a higher risk of stomach and duodenal ulcers but a lower risk of stomach (gastric) cancer.

- Mixed where (more common) H. pylori infection occurs in both the antral and body portion of the stomach, typically resulting in no net change in stomach acid secretion.

References:

[1] Yarandi SS, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Mostajabi P, Malekzadeh R. Overlapping gastroesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome: increased dysfunctional symptoms. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Mar 14;16(10):1232-8. [2] Verma S, Jackson W, Floum S, Giaff er MH. Gastroesophageal reflux before and after Helicobacter pylori eradication. A prospective study using ambulatory 24-h esophageal pH monitoring. Dis Esophagus 2003;16:273-278. [3] Tefera S, Hatlebakk JG, Berstad A. Th e eff ect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Th er 1999;13:915-920. [4] Manifold DK, Anggiansah A, Rowe I, Sanderson JD, Chinyama CN, Owen WJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux and duodenogastric reflux before and after eradication in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001 May;13(5):535-9. [5] Wu JC, Chan FK, Wong SK, Lee YT, Leung WK, Sung JJ. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on oesophageal acid exposure in patients with reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002 Mar;16(3):545-52. [6] Garrido Serrano A, Lepe Jiménez JA, Guerrero Igea FJ, and Perianes Hernández C. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease. REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid). 2003. Vol. 95. N.° 11, pp. 788-790. [7] Corley DA, Kubo A, Levin TR, Block G, Habel L, Rumore G, Quesenberry C, Buffler P, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a case-control study. Helicobacter. 2008 Oct;13(5):352-60. [8] Shirota T, Kusano M, Kawamura O, Horikoshi T, Mori M, Sekiguchi T. Helicobacter pylori infection correlates with severity of reflux esophagitis: with manometry findings. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(5):553. [9] Chung SJ, Lim SH, Choi J, Kim D, Kim YS, et.al. Helicobacter pylori Serology Inversely Correlated With the Risk and Severity of Reflux Esophagitis in Helicobacter pylori Endemic Area: A Matched Case-Control Study of 5,616 Health Check-Up Koreans. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17(3):267. [10] Labenz J, Jaspersen D, Kulig M, Leodolter A, et.al. Risk factors for erosive esophagitis: a multivariate analysis based on the ProGERD study initiative. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Sep;99(9):1652-6. [11] Schenk BE, Kuipers EJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Eskes SA, Meuwissen SG. Helicobacter pylori and the efficacy of omeprazole therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 Apr;94(4):884-7. [12] Rubenstein JH, Inadomi JM, Scheiman J, Schoenfeld P, Appelman H, Zhang M, Metko V, Kao JY. Association between Helicobacter pylori and Barrett’s esophagus, erosive esophagitis, and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Feb;12(2):239-45. [13] Chait MM. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: Important considerations for the older patients. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Dec 16;2(12):388-96. [14] el-Serag HB, Sonnenberg A. Opposing time trends of peptic ulcer and reflux disease. Gut. 1998;43(3):327. [15] Vicari JJ, Peek RM, Falk GW, Goldblum JR, et.al. The seroprevalence of cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori strains in the spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(1):50. [16] Vaezi MF, Falk GW, Peek RM, Vicari JJ, et.al. CagA-positive strains of Helicobacter pylori may protect against Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(9):2206. [17] Kuipers EJ, Lundell L, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Havu N, et.al. Atrophic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux esophagitis treated with omeprazole or fundoplication. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(16):1018. [18] Personal communication, January 16, 2014. [19] Hirschowitz BI. A critical analysis, with appropriate controls, of gastric acid and pepsin secretion in clinical esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1991 Nov;101(5):1149-58. [20] El-Serag HB, Sonnenberg A, Jamal MM, Inadomi JM, Crooks LA, Feddersen RM. Corpus gastritis is protective against reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 1999 Aug;45(2):181-5. [21] Koike T1, Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Kato K, Shimosegawa T, Toyota T. Helicobacter pylori infection inhibits reflux esophagitis by inducing atrophic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 Dec;94(12):3468-72. [22] Fujiwara Y1, Higuchi K, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, Matsumoto T, Arakawa T. Association between gastroesophageal flap valve, reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s epithelium, and atrophic gastritis assessed by endoscopy in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(6):533-9. [23] Weck MN1, Stegmaier C, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Epidemiology of chronic atrophic gastritis: population-based study among 9444 older adults from Germany. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Sep 15;26(6):879-87. [24] Gao L, Weck MN, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Body mass index, chronic atrophic gastritis and heartburn: a population-based study among 8936 older adults from Germany. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010 Jul;32(2):296-302. [25] Smith JL, Opekun AR, Larkai E, Graham DY. Sensitivity of the esophageal mucosa to pH in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 1989;96:683-689. [26] Hallberg K, Abrahamsson H, Dalenbäck J, Fändriks L, Strandvik B. Gastric secretion in cystic fibrosis in relation to the migrating motor complex. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001 Feb;36(2):121-7. [27]Ledson MJ, Tran J, Walshaw MJ. Prevalence and mechanisms of gastro-oesophageal reflux in adult cystic fibrosis patients. J R Soc Med. 1998 Jan;91(1):7-9. Vic P, Tassin E, Turck D, Gottrand F, Launay V, Farriaux JP. Frequency of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and in young children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Pediatr. 1995 Aug;2(8):742-6. [28] Fridge JL, Conrad C, Gerson L, Castillo RO, Cox K. Risk factors for small bowel bacterial overgrowth in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007 Feb;44(2):212-8. Lisowska A, Wójtowicz J, Walkowiak J. Small intestine bacterial overgrowth is frequent in cystic fibrosis: combined hydrogen and methane measurements are required for its detection. Acta Biochim Pol. 2009;56(4):631-4. [29] Yancy WS Jr, Provenzale D, Westman EC. Improvement of gastroesophageal reflux disease after initiation of a low-carbohydrate diet: five brief cased reports. Altern Ther health med. 2001. Nov-Dec; 7(6):120,116-119. Austin GL, Thiny MT, Westman EC, Yancy WS Jr, Shaheen NJ. A very low-carbohydrate diet improves gastroesophageal reflux and its symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2006 Aug;51(8):1307-12. [30] R C Orlando, E M Bozymski. Heartburn in pernicious anemia–a consequence of bile reflux. New England Journal of Medicine 10/1973; 289(10):522-3. [31] Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, Vela M, Zhang X, Sifrim D, Castell DO. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut. 2006 Oct;55(10):1398-402. [32] Siddiqui A, Rodriguez-Stanley S, Zubaidi S, et al. Esophageal visceral sensitivity to bile salts in patients with functional heartburn and in healthy control subjects. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:81-85.

I have been doing low fermentable carb diet for a short period of time now and I do not take any PPIs. I have notice a difference in the bloating and gas in my stomach but I still have a very irritated esophagus. How long does it take to heal the irritation and is there anything I can do to help this heal faster?

Hi Tara,

The important thing is to completely control the reflux. If you still have some reflux, you’re not there yet. There are a number of ways to address this depending on your situation, foods, meds and behaviors. We can help with consultation. Once reflux is controlled, it could take some time for irritated of inflamed esophageal tissue to heal. In the interim, watching spicy or acidic foods might help or taking a drink of water after such foods.

I wonder if you’ve come across any connection between reflux and gallbladder removal. I’d never had any digestive issues until one day, after eating an apple, I had a major attack and was diagnosed with several gallstones (this disease runs in my family). I had surgery about a month later. Since then, my life is completely changed. I have had, for lack of a better diagnosis, “reflux,” according to doctors I’ve seen. I put this in quotes because my discomfort doesn’t come in the form of burning, etc. It’s usually flat-out pain right at the base of my sternum–like something is stuck and not making it down. It was minor at first, and short-lived (about 15-30 minutes) and mostly happened with chicken and rice, some very fibrous fruits and vegetables, and definitely wheat, which I do not eat anymore (I am not allergic to gluten or sensitive to it either). Over two years later, I became quite sick one night, vomiting about 6 times in two hours, and have never been the same. I was then diagnosed with a hiatal hernia. Now in addition to the original pain, I get terrible chest pains and what feels like a major gas blow-up in my chest usually about 1-2 hours after eating. It often extends into my neck and especially my shoulder blades. Exercise often exacerbates it (which is how I found this site, by searching that connection). Since then, it’s been difficult to eat most foods and it’s very inconsistent. They might be okay one week, and horrible the next. It comes in waves too; it’ll be bad for 2-4 weeks, then might clear up for another month. None of the usual reflux “triggers” seem to apply to me; those foods (caffeine, alcohol, citrus, etc.) are just as hit-or-miss. In fact, I’ve mostly survived on ice cream, 2% organic milk and protein drinks; they seem to be the only things that do not cause a problem and keep my blood sugar from plummeting. PPIs made absolutely no difference. I have PVCs and they have gotten worse during this, as have palpitations. Thoroughly checked out by a cardiologist; no problem there. MRI done to be sure no stone was left behind; that was negative too. Many people in other forums have described similar post-surgery issues. Have you ever researched or heard about a possible cholecystectomy/reflux connection?

Hi Joyce, I can’t comment on your specific case, but I have heard stories similar to yours. There are mixed research findings on this connection. Here’s a study where no connection was found, but the paper references several other studies (reportedly less controlled) that found there was a connection. Bile is believed to be a contributing factor in reflux symptoms, particularly in cases where acid is absent – for instance when someone is on PPIs. I can imagine bile reflux occurring more regularly after gallbladder surgery as the control of bile release (after meals when it has a job to do) is lost. It make sense that controlling reflux with a diet like Fast Tract would help.

You mention the importance of water in your book. What are your thoughts about drinking water with meals? Some discourage it.

Hi Derek,

Yes, I do talk about many important health aspects of water in the Fast Tract Digestion books. Water with meals should reduce the viscosity of digesting food (chyme) potentially allowing gas to escape more freely via belching – important for GERD and possibly IBS. Adequate water with meals should also improve motility, one of the biggest factors in SIBO.

I just wanted to give an update on my earlier post. I have hand an endoscopy for the reflux symptoms. He told me it looked good in there right after the procedure. He went ahead and took biopsies as a precaution. (I think for Celiac and H. Pylori) I get the results on Tuesday. I am still having the feeling of air trapped in the esophagus ( I will have a small burp but the feeling is still there), some heartburn and the feeling something is stuck in my throat with some throat tightening. It is causing me to great anxiety and I am already a highly anxious person. I get these feeling sometimes when I haven’t eaten in many hours and also sometimes just after drinking water. Do you think this could be related to the foods I am eating and fermentation or might it be anxiety triggered by my original experience? Maybe a little of both? I tried an anxiety medicine which did not ease my symptoms. I just don’t know what my next step should be. I have tried digestive enzymes and I seem to get a little more burning and gas when I take them with a meal.

Hello Tara,

I have been struggling with many of your symptoms for a long time. One thing that helped me with my anxiety was a combination of 3 products by a company called PASCOE. These products are oral drops that you mix with 1 to 1.5 liters of water and sip throughout the day. The 3 products are Nux Vomica (30 drops), Zincum (30 drops) and Lymphdiaral (50 drops). I too suffer from SIBO and reflux and get lots of joint pain and feelings of anxiety. This combination of 3 products has eliminated my anxiety and significantly reduced my joint pain by helping to drain my lymphatic system. In addition I have also completed two 30 day colon cleanses by Ultimate Lifespan. You can find them on Amazon. My SIBO is still not eliminated, but I have experienced a great improvement. Of course I am also following a strict non carbohydrate diet.

Mr Robillard, I would like to consult with you if you think you can help. In fact I would pay you every last cent to my name if you can:)

Here’s the deal, I have a particularly interesting case… I have hashimoto’s hyperthyroid, liver does not convert to t3 so I have to take both t3 and t4, I have SIBO-constipation (as in 24-7), also PCOS.

So here’s where it gets interesting…when I go on an elimination diet (I tried this elim. diet for of 3weeks, no improvement w/ constipation), eliminating all potentially fermenting carbs (intending to add back in the lowest FP ones one by one) I end up extreme acid reflux and heartburn, have to pee at least 1x per hour even at night (not exaggerating), extremely high pulse rate, and some heart palpitations, my bm’s looked like olive oil and had no solid portions, and I gained about 6lbs in those 3 weeks.

During this time I was maintaining about 1800 cal. per day (I am 36, 5foot, female), eating coconut oil, chicken, fish, carrots, small amounts of spices, adequate salt, ghee, mct oil, and well cooked spinach and green beans.

Why would I get worsened acid reflux with this?

I am now back on a low fodmap/no starch diet, I am now taking ADP oil of oregano, constipation is improving, however slightly, but acid reflux is getting outta control, I think it’s damaging my esophagus so I will probly have to quit it soon and rely on diet alone.

Questions on your diet recommendations…

1. You mention fasting but fasting can down-regulate metabolism and exacerbate hypothyroid and is generally not recommended for people with constipation…would you still recommend it for someone like me?

2. Many of the foods you recommend are hugely problematic for me like watermelon, brussel sprouts, cabbage, onions… these cause immediate problems for me. How do I know if the other things are causing problems but just not immediate?

3. I cannot eat rice, gives me painful inflammation, gives same symptoms as gluten.

4. I cannot find sebago or pontiac potato and russet are fairly high in starch which is hard to digest so I’m not sure where to go from here…

5. Sugar (50/50 fructose/glucose), and all fruits give me worsening of bacteria overgrowth and bacterial vaginosis.

Can you help??

Hi Jessie, Sorry to hear that you have to endure these health issues. Given the complexities of your case, its not possible to address your issues outside of our consultation program. I will have someone contact you off line. I agree with you that uncontrolled reflux is not something you should let persist long term.

I have received your consultation info via email. However, I think I will give your Fast Tract diet another go for a few weeks before I do a consultation with you. I have already read your book of course, but today I spent much of the day reading up on all your blog articles as well(I esp. loved your post on RUMPS) and I determined that maybe the potatoes (I will keep looking for the other low FP types you mention) will be the best carb source for me as opposed to fruits. So this time around I will eliminate all fruits including watermelon, and use russet potato as my sole carb. source, and of course avoid all veg. except carrot, spinach, and green onion tops which I’m pretty sure I’m ok with. I will also calculate out my total carb per meal so that I stay between 35-40% from total calories. I think this seems like a good plan for now. This way I can rule out fructose malabsorption.

After all the reading about starch that I have done today, I still don’t quite understand why russet potatoes (higher in starch) are considered less likely to cause GI symptoms (per your book) than lower starch potatoes like red potatoes for example (you mentioned them in a reply on this website somewhere). Since they are high in starch wouldn’t they also be high in resistant starch which you advise against?

Also, I’ve red that cold storage (under 45F degrees) of fresh potatoes turns the starch to sugar (glucose I would assume)… would this be a good thing?

P.S. thank you and I really appreciate your science based approach!

Sounds like a plan Jessie. One word of caution. Given your symptoms, I recommend watching FP levels and overall carb counts. 35-40% calories from carbs is quite high. The FP values for foods may be “effectively” higher in people suffering from malabsorption. Lower FP foods are still preferred, but lower total carb counts can help early on.

The Russet is a lower FP potato not because of the starch content itself, but because of it’s higher ratio of amylopectin over amylose starch. The same goes for red potatoes – it depends which type. For instance, the Pontiac potato is a “red” potato, but has a lower FP than the Russet.

Also, cold storage increases resistant starch. Glucose content does not change.

Thank you kindly for the clarification!

I understand the logic of keeping the total carb pretty low in order to reduce the bacteria overgrowth, however, I’ll have to take my chances because too low carb as I mentioned causes some very extreme symptoms for me, including a worsening of acid reflux. I know I’m probably a unique case because usually the opposite happens! I guess I really just gotta try it because I’ve exhausted all my other options.

I’ll give it a few weeks and if I’m still getting worse I will contact you.

Happy Friday!

Just use your best judgement Jessie and good luck. Please post on your experience.

I just wanted to add what works for me. First low carbohydrate diet of course but i actually can eat carbs with reduced reflux symptoms when i drink carbonated water with the food, in my case its carbonated mineral water, but i think any carbonated drink should help.

Hi Dr. Robillard

I posted your H.Pylori blog post on a popular SIBO/Gut healing protocol Facebook Group called the Gut Healing Protcol, and the moderator, John Herron wrote this in response. (Someone had indicated their GERD was caused by h.pylori which prompted me to forward your article). I would love you thoughts. Thanks!

Our stomachs should be producing stomach acid, failure to do so is what leads to SIBO in the first place. When h.pylori shuts down the stomachs ability to produce this acid it needs to be replaced or the ability for the stomach to produce it needs to be fixed quickly. I’ve seen too many MD’s give people PPIs when treating h.pylori and many of these people continue to take them life! Then they come here with a whole host of problems, including many conditions probably caused by mineral deficiencies. If your doctor has another approach to restoring HCl we would like to hear it. The articles view that too little stomach acid does not cause GERD is completely wrong, adding HCl has helped far too many people completely get rid of GERD, including myself. The only study the author quotes was sponsored by the company that manufactures Prevacid, one of the best selling protein pump inhibitors. This really negates everything else said by the author on HCl.

Hi Bearsmom,

Thanks for this feedback from John. I welcome his comment opening a healthy discussion on this topic.

I will address the main points of John’s comments:

1. “Our stomachs should be producing stomach acid, failure to do so is what leads to SIBO in the first place. “

NR: I agree in part. Our stomach should be producing stomach acid. But failure to do so is only one possible cause of SIBO. There are many others including carbohydrate malabsorption due to enzyme deficiency, motility problems, gastritis (gut infections), and a Western diet with more carbs than our body can digest and absorb, especially as we get older.

2. “I’ve seen too many MD’s give people PPIs when treating H.pylori and many of these people continue to take them life! Then they come here with a whole host of problems, including many conditions probably caused by mineral deficiencies. If your doctor has another approach to restoring HCl we would like to hear it. “

NR: I see no role at all for PPIs in GERD and never recommend people take them. In one of my other articles on GERD in the series, I talk about the problems with these drugs. But the point of this article was that most people with acid reflux have adequate amounts of stomach acid. I would only support restoring HCl in cases where a known deficiency exists.

3. “The articles view that too little stomach acid does not cause GERD is completely wrong, adding HCl has helped far too many people completely get rid of GERD, including myself. The only study the author quotes was sponsored by the company that manufactures Prevacid, one of the best selling protein pump inhibitors. This really negates everything else said by the author on HCl.”

NR: Recall my conclusion in the article:

While low stomach acid may not provoke as many typical GERD symptoms (which are likely more dependent on the acid component), it might be expected to lead to more episodes of “non-acid” reflux.“ This conclusion is based on several lines of evidence:

1. Personal communication with one of the top GERD experts in the US and reading his body of work on the topic.

2. Several studies (references 20 – 24), including two large studies, showing that chronic atrophic gastritis (the most common cause of low stomach acid after PPIs) reduces the risk of acid reflux, heartburn and esophagitis.

3. The new drug application for a PPI showing GERD patients had typical levels of stomach acid. Yes, the work was done by a pharma company, but I have no reason to believe they fudged the data in a submission to the FDA.

Perhaps John Herron would:

1. Address the findings in references 20-24 cited in the article and not performed by a pharma company.

2. Explain why 80% of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients have acid reflux despite evidence that these patients produce normal amounts of stomach acid (my conclusion was pancreatic insufficiency leading to carb malabsorption).

3. How low carb diets control acid reflux without modulating stomach acidity.

4. Why bicarb works so well for most people with heartburn.

5. Provide the evidence that betain HCl relieves acid reflux (I already agree that betain may help a subset of people experiencing non-acid reflux.).

Norm thanks. I forwarded your response to that FB group so hopefully it will be helpful for some people there! It helped clear my thinking on this issue too.

Dear Norm,

I have been battening some type of burning for months now. I get a burn in my stomach with a lot of rumbling and my throat and ears feel like they are on fire. I’ve gone gluten free and basically am only eating meat and veges. Still having issues. My ND seems to think it may be low stomach acid and have me Okra Pepsin e3. I still am having many sore throats and ears will itch or burn. I have had stool tests done saying that gut flora is off ( more bad than good) and it also showed increased lysozyme, increased alpha anti chimoteypsin, and poor pancreatic output of all enzymes. Mine was extremely low. I was told I had gut dysbiosis and needs to eat high protein, gluten free low carb diet. I’m still not getting better. Had a capsule endoscopy done and they said they saw inflammation and some ulceration and then a week later regular endoscopy showed nothing. Have not got my results back from biopsies taken for celiacs and h. Pylori. I’m assuming celiacs will show negative due to I have been gluten free for months. Do you think your diet could help. I was thinking about trying SCD but not sure if that’s the right one for me. Seems like there are many foods on that diet that make my symptoms worse. What are your thoughts? So frustrated!!!!!

Greetings! Have you read Dr. Robillard’s Book, Fast Track Digestion:IBS? I can’t speak to all of your test results, but, in trying the Fast Track Digestion approach, you may need to lower your protein intake, and increase your fats up to 70%. If your burning symptoms are gas-driven, then the large amounts of protein you are eating, may feed the microbial overgrowth (some microbes digest proteins too). I had more digestive relief when I followed the trouble shooting section of the book which recommended reducing protein and adding fat. I take fat in the form of grass fed butter, olive oil, small amount of cheese, small amount of avocado. Mostly grass fed butter and olive oil and fatty meat and fish. Microbes dont eat fat. I bought a kitchen scale so I could track how much protein I was eating. It adds up quickly and I realized I could reduce it and felt better when I added more fats. Chewing your food very well, skipping breakfast several times per week to allow the cleansing waves to sweep the bacteria out of the upper part of your small intestine, and meal spacing (4 or more hourse between meals). All of these things add up. It may take several weeks to start to see improvments. Check in at the forum for more encouragement. I agree there are a lot of fermentable foods on the SCD diet, and if those foods are bothering you, it is likely you have SIBO. Diet is slow, but effective. Keep a food journal too. Best of luck!

Yes i recently had the h pylori bacteria and i was on the triple anti botics and i went back and got a stool sample and my test came back negative, Now I’m having another symptom, I now throw up everything i eat and drink. My question is can h pylori cause acid reflux

I’ve been feeling better since I’ve been on the fast track diet now about 3-4 months. I still have some reflux, but it is so much improved. I find it hard to give up chocolate though. Anyway, I’m still taking Nexium 40mg. and I want to get off of it. Do you advise lowering the dose first or going cold turkey?

Thank you for your article. Do you think that h pylori can cause SIBO? I have recently been diagnosed as positive for both. I have no symptoms other than daily bloating. I keep hearing that I am supposed to eradicate the h pylori first or I will never get rid of the SIBO however I have also read that h pylori could be helpful in some ways, as you mentioned, and if I have no particular stomach symptoms it is better to leave it alone. So many people complain of worse symptoms post h pylori protocol. Do you have any thoughts on all that?

Hi Chandra,

Of course, talk to your doctor, but here is my view. Forgetting for a second Dr. Martain Blaser’s love affair with H. pylori expressed in his otherwise excellent book “Missing Microbes”, long term infection with this bacterium can lead to atrophic gastritis where part’s of the stomach loose their ability to function. This can lead to hypochlorhydria (low stomach acid – increased risk of stomach cancer) or hyperchlorhydria (too much stomach acid – risk of ulcers). Aggressive treatment of H.pylori with combination antibiotics is warranted. Then SIBO can be addressed with changes in diet, behaviors and potentially some distinct supplements depending on any specific deficiencies identified.

Hi Norm, I have just found your site today. I am suffering from GERD symptoms and I am looking for answers. I took PPI’s for 2 months and symptoms were removed but I have been off them for about three months (and do not want to go back on them) and pain has returned with gradually increasing intensity. Also, lately a lot of burping – which has reduced with HCL Betaine supplements. I have a couple of questions.

Does coffee reduce Lower Esophageal Sphincter strength and increase transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation.

From what I have read you are focusing on starving out the overgrowth, but from my research this is only a temporary solution to SIBO with possible long term detrimental effects on good bacteria in large intestine.

Could it be that both low stomach acid and SIBO are distinct causes of GERD? – that can also feedback on each other?

My understanding of what some people are saying is that lowered stomach acid production reduces Lower Esophageal Sphincter closure strength – although I haven’t found much in the way of scientific studies demonstrating the link except https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1418956/. This would explain the reports/claims that increasing acid levels reduces reflux as well as having an effect on increasing intestinal motility and reducing SIBO.

It can get a bit complex at times. E.g. Pre-biotics are meant to be good for large intestine health but can feed SIBO. There is a train of thought that massive doses of beneficial bacteria can get rid of SIBO – or at least strongly contribute to getting rid of it. https://www.elixa-probiotic.com/articles/ and https://www.elixa-probiotic.com/videos/ Your thoughts??