People who have asthma often ask “Why do I have both asthma and acid reflux”. On the surface, chronic acid reflux (GERD) and asthma appear to be quite separate conditions with little in common.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory lung disease that causes narrowing of the airways, affecting over 20 million people in the US including up to 6 million children. Symptoms include: wheezing, coughing, difficulty breathing, tightness in the chest and flare-ups associated with allergic reactions or following exercise.

The exact cause of asthma is unknown, but both genetic and environmental factors are thought to be involved. Flare-ups of asthma appear to be allergic in nature as most people with asthma have specific allergies. Allergens that can trigger attacks include cat or dog dander, dust mites, cockroaches, mold and other irritants like cigarette smoke. Asthma diagnosis is made based on a physical exam, breathing tests and a review of one’s medical history.

Chronic acid reflux, often referred to as GERD, which stands for gastroesophageal reflux disease, is a chronic condition caused by the repeated refluxing of stomach contents into the esophagus. Approximately sixty million people in the US suffer with symptoms related caused by acid reflux. The most common symptom is heartburn, described as a burning sensation behind the breastbone. Other reflux symptoms include abdominal pain, cough, sour taste, sore throat, hoarseness, laryngitis, asthma like symptoms (one sign of a possible link) and sinus irritation. Smoking, pregnancy, obesity, hiatal hernia and tight fitting clothes can make symptoms worse.

During acid reflux, the group of muscles at the top of the stomach, called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), are unable to keep the stomach’s contents from entering the esophagus. The esophagus is not protected by the same mucous layer that coats the inside of the stomach. The result is painful damage to the esophagus. Diagnosis of GERD is generally accomplished by a doctor reviewing a patient’s symptom history in detail including frequency of heartburn, and related symptoms.

If diagnostic tests are required, they may include upper gastrointestinal endoscopy that allows your doctor to look at the lining of your esophagus, stomach and first part of your small intestine using a miniature camera. Damage or irritation to the lining of the esophagus is a common hallmark of GERD. If symptoms persist, additional tests may include manometry to measure how tightly your LES closes as well as 24 hour pH monitoring to measure how much acid is leaking into your esophagus and how long it remains there.

For some time a connection between asthma and acid reflux has been recognized but the reason for the connection has remained a mystery. As many as 80 percent of asthmatics suffer from abnormal gastroesophageal reflux compared to about 20 – 30 percent of non asthmatics (1, 2). Some asthmatics have GERD with classic symptoms while others shown to have GERD by pH monitoring don’t have classic symptoms and are considered to have “silent GERD” (3). A better understanding of the underlying cause of GERD may shed more light on the connection between this condition and asthma.

What is the true cause of acid reflux?

As a heartburn sufferer myself, I was surprised to find that my symptoms disappeared when I started a carbohydrate restricted diet. I wondered if carbohydrates somehow caused my symptoms and if so, how? I reviewed the leading theory suggesting that certain (trigger) foods, caffeine, or alcohol could relax or weaken the LES muscles and trigger reflux. This concept did not make sense to me and didn’t seem to fit the facts.

As I tried to understand how carbohydrates might trigger reflux and symptoms, I came up with an idea. If some carbohydrates were not fully digested and absorbed in the small intestine, they would be available as food for intestinal bacteria through a process called fermentation. Well fed bacteria make lots of gas. It would be like dropping a Mentos in a bottle of Coke. That much pressure would surely be capable of driving acid reflux into the esophagus and even the lungs. Could bacteria, malabsorbed carbohydrates and fermentation be causing acid reflux and perhaps even asthma?

Bacteria in our gut

The human large intestine contains over 100 trillion microbes belonging to more than 50 genera and over 500 species. These organisms live on nutrients from our diet that we are unable to digest, and in exchange, produce some vitamins and other nutrients that nourish our own cells. Microbes allow us to use food about 30 percent more efficiently and also compete with disease causing germs that might otherwise gain a foothold making us ill. Bacteria outnumber other intestinal microbes by far though some protozoa, fungi and other tiny creatures reside here as well.

While a large diverse population of bacteria is healthy in the large intestine, relatively few bacteria should be present in our small intestine where our own critical nutrient absorption takes place. Normally, the numbers range from zero in the stomach and first part of the small intestine to about one million bacteria per milliliter (mL) in the last part of the small intestine where the large intestine begins. One million bacterial cells is actually a very small amount compared to the trillions in the large intestine.

The number of bacteria in the upper digestive system is controlled by the constant movement of food, acid produced by the stomach, bile, intestinal immunity and the production of mucin that make it difficult for bacteria to adhere to the intestinal surface. Importantly, our efficient digestive process normally limits the amount of nutrients available for bacterial growth. When this balance is disrupted, resident bacteria can rapidly overgrow in the small intestine.

The term Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), refers to bacteria, mostly from the large intestine, invading and overpopulating the small intestine. SIBO is defined as having greater than 100,000 bacteria per milliliter in the upper part of the small intestine. Despite the many defenses the body has to prevent overgrowth, SIBO is common and continues to be linked to a growing number of disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s and celiac disease and cystic fibrosis.

When SIBO occurs, normally harmless bacteria overgrow and produce lots of gas (carbon dioxide, hydrogen and methane). If too much gas is produced but not dissipated by intestinal absorption or metabolism by gas consuming bacteria, it can create pressure in the small intestine and stomach that actually drives the reflux of stomach contents past the LES into the esophagus. People with weakened or defective LES muscles will be more susceptible to reflux because less gas pressure will be required to push open the LES.

Can fermentation create enough gas pressure to cause acid reflux? I believe it can. Years ago, as a research scientist, I routinely grew bacterial cultures often working with intestinal strains of bacteria. The growth media contained carbohydrate (typically glucose) because gut bacteria prefer to consume carbohydrates for energy. I was amazed at the amount of gas that most strains could produce. As little as thirty grams (the weight of six nickels) of carbohydrate can give rise to ten liters of hydrogen gas. So much (flammable) gas can be produced by intestinal bacteria that there have been well documented cases of explosions during intestinal surgery (4,5).

The following nine points of evidence convinced me that carbohydrate malabsorption coupled with SIBO may be the ultimate cause acid reflux and perhaps a factor in asthma:

- Management of dietary carbohydrates improves reflux symptoms and reduces esophageal acid exposure. (6,7,8). I believe reducing carbs is an effective treatment because intestinal bacteria are denied fuel which limits their growth and ability to produce gas.

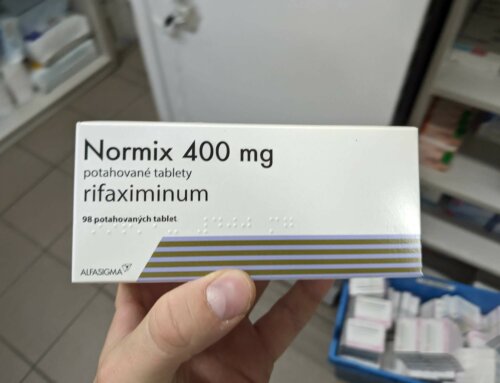

- Treatment of GERD patients with the antibiotic erythromycin decreases gastro esophageal reflux and increases apparent LES pressure (9,10). The authors suggested that erythromycin had increased the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure in the these patients. But how can an antibiotic tighten these muscles? LES pressure is measured by inserting a tube through the LES that detects how tightly the LES closes. In this case the LES appeared be closing more tightly after treatment with erythromycin. Possibly, the authors failed to recognize the growth inhibiting effect of erythromycin on intestinal bacteria and how that would limit reflux causing gas. What appears to the authors as “strengthening the defective LES in GERD patients” is, in my opinion, a decrease in intragastric (stomach) gas pressure because erythromycin is inhibiting the intestinal microbes that were producing the gas in the first place. The LES appears to exhibit increased pressure but the effect is actually caused by a decrease in intragastric pressure that no longer pushes as hard on the LES.

- Consumption of the carbohydrate fructose oligosaccharide (FOS), which is indigestible by humans, but fermented by gut bacteria produces intestinal gas and increases the number of reflux episodes and symptoms of relfux (11). The authors noted an increase in something called transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs). In other words, the LES opened more as if it was relaxing. I believe these “Lower esophageal sphincter relaxations” described by the authors actually represent the LES being “forced” open by gas pressure. Consuming FOS ensures 100% malabsorption. The fermentation of FOS by gut microbes makes enough gas to pressurize the small intestine and stomach and force open the LES causing reflux and heartburn in susceptible people.

- In GERD patients, reflux was associated with an increase in intra-abdominal (gas) pressure and belching (12,13). The increase in intra-abdominal gas pressure and belching is consistent with the idea that gas produced in the small intestine from carbohydrate fermentation can create gas pressure in the stomach and cause belching as the gas escapes into the esophagus. The only difference between belching and acid reflux is that the gas pushes stomach contents into the esophagus in the later case and escapes on its own in the former.

- Cystic fibrosis (CF) patients have a very high (up to 80%) prevalence for GERD and exhibit well documented carbohydrate malabsorption and bacterial overgrowth associated with pancreatic digestive enzyme deficiency due to blockage of pancreatic ducts with thick mucus (14,15,16). After studying the connection between GERD and CF as well as the details of carbohydrate malabsorption in CF, I am convinced that pancreatic enzyme insufficiency leads to malabsorption, SIBO and the reflux-related symptoms so prevalent in cystic patients.

- The prevalence of GERD in IBS patients (39%) and IBS in GERD patients (49%) is much higher than the prevalence of GERD (19%) or IBS (12%) in the general population indicating a relationship between the two conditions (17). IBS has been clearly linked to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth via hydrogen breath testing and, like GERD, has been treated successfully with carbohydrate restriction as well as antibiotics (18,19,20,21,22). This evidence is consistent with SIBO playing a role in both conditions.

- Half of GERD patients taking PPI drugs showed evidence of SIBO by glucose breath testing compared to only 25% of IBS patients not taking PPIs. Eighty-seven to ninety percent of SIBO-positive patients (with GERD or IBS) showed improvement after antibiotic treatment (23). I believe the SIBO-positive results in both groups would have been higher if the study employed the lactulose breath test instead of the glucose breath test. Lactulose is not digested or absorbed in the small intestine and can detect bacteria (fermenting the lactulose and producing hydrogen) throughout the entire length of the small intestine. Glucose is rapidly absorbed in the first part of the small intestine and will only detect bacteria if they are present in this region. Dr. Pimentel found that 78 percent of IBS patients tested at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center had SIBO as indicated by a positive lactulose breath test (18).

- GERD is associated with obesity and carbohydrate restriction improved symptoms and reduced esophageal acid exposure in obese patients regardless of weight loss (24,25,26). Obese people consume more food, especially carbohydrates, which I believe can lead to “volume based” malabsorption causing SIBO and reflux.

- A significant number of GERD patients report new symptoms following fundoplication surgery that include excessive gas (abdominal gas and flatulence), bloating, diarrhea and abdominal pain (27, 28,29). The procedure is aimed at preventing reflux, but the side effects are indicative of trapped stomach and intestinal gas as would be expected with malabsorption and SIBO.

The connection between gut and lungs

Normally, stomach acid forms a barrier between bacteria in your intestines and your esophagus, lungs and sinuses because bacteria are killed by stomach acid. Acid reflux can surpass this protective mechanism, especially if stomach acid is neutralized. When acid neutralizing drugs are used (PPIs, H2 blockers and even antacids), bacteria from the intestines are more likely to overgrow and survive in the small intestine and stomach. Reflux can cause these bacteria to enter the esophagus and potentially the lungs and sinuses. People on acid blocking meds are more susceptible to respiratory infections most likely from bacteria originating in their own intestines.

This connection has been proven in a large study linking acid reducing medications to pneumonia. A study of more than 364,000 people led by Robert J.F. Laheij at the University Medical Center St. Radboud in Nijmegen , the Netherlands , found that the risk of pneumonia was almost double for people taking proton-pump inhibitors for prolonged periods compared to people not taking such drugs (41). The increased risk of respiratory infection was also seen in children taking acid reducing medication (42).

As further proof of the connection between reflux and lung problems, Belgium researchers found that the potent antibiotic azithromycin reduced gastroesophageal reflux as well as esophageal acid exposure and the concentration of bile acids in fluid removed from the lungs of lung transplant patients (43). Similar to the erythromycin studies cited above, the authors did not consider that the profound effect might be due to the antibiotic treatment inhibiting gut microorganisms. In this case, stomach acid and bile were being refluxed not only into the esophagus, but directly into the lungs. Azithromycin treatment helped prevent reflux into the esophagus and lungs likely via its effect on SIBO inhibition. The results were quite beneficial for the patients.

Asthma and GERD

In an attempt to understand the connection between GERD and asthma, large multicenter studies were conducted to determine if treatment of GERD with potent PPI drugs would reduce asthma symptoms and improve lung function in poorly controlled asthmatics that had GERD or silent GERD. Studies with the PPI drugs lansoprazole and esomeprazole were conducted to determine if the treatment of GERD with these drugs would have a positive impact on asthma. In each case, the drugs did not improve asthma symptoms or lung function (44,45).

The study employing esomeprazole (Nexium), called the SARA study (for study of acid reflux and asthma), concluded that “gastroesophageal reflux is not a likely cause of poorly controlled asthma”. The authors reasoning was that Nexium “treated the GERD” and the asthma did not improve, therefore GERD can’t be a cause of asthma. It should come as no surprise that I disagree with this conclusion and find myself surprised that no one caught the flaw in this logic.

The flaw is making the assumption that Nexium (or any other acid reducing drug) eliminates any threat from GERD. There is no evidence I am aware of that shows that Nexium and other PPI drugs stop reflux. The drugs simply shut down the production of stomach acid. The above studies suggest that acid alone is not the cause of difficult to treat asthma. But uncontrolled reflux ensures that digestive enzymes, bile and bacteria continue to insult the esophagus, lungs and sinuses. One or more of these substances likely plays a role in the continued exacerbation of asthma even when patients are given PPI drugs. Prolonged use of PPI drugs may actually make things worse by blocking the production of stomach acid that prevents gut bacteria from entering the esophagus, lungs and sinuses.

But what would happen if you could stop all reflux, not just neutralize stomach acid? Would that help people with asthma and GERD? This idea has actually been tested. Fundoplication operations dramatically reduce reflux itself. And it turns out that fundoplication operations dramatically improve asthma symptoms. And, this results in a significant reduction in medicine usage. Research led by Sebastian Johnston at Imperial College London points to bacteria as one likely suspect in the exacerbation of asthma. The team treated 278 adults diagnosed with asthma with either placebo or telithromycin, an antibiotic used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Treatment was initiated within 24 hours after an acute exacerbation of asthma requiring short-term medical care (46). The results of the study showed the group treated with the antibiotic had a significant improvement in symptoms. Though the other endpoint -peak expiratory flow in the morning at home – was not significantly different, the researchers concluded that there was evidence of the benefit of telithromycin in patients with acute exacerbations of asthma. They also noted that the mechanisms of benefit remain unclear. The contribution of gut bacteria via reflux appears to be the most promising candidate to explain these findings. Clearly GERD and asthma are very different and complex conditions that share a link. People undergoing treatment for either condition should not make any immediate changes before consulting their own healthcare provider. Your own health care provider may offer diagnostic tests to determine if you suffer from various types of carbohydrate malabsoption such as lactose or fructose intolerance. Some health care providers provide screening for SIBO itself. If you, or someone you know have asthma which is not well controlled, I suggest talking to your doctor about initiating one of my diets that control acid reflux (clinical research studies support both approaches). One approach is an overall low carbohydrate diet described in my book Heartburn Cured. The other approach documented in my new book, Fast Tract Digestion Heartburn limits only difficult to digest carbohydrates. Are you ready to put the Fast Tract Diet into action? Try the Fast Tract Diet Mobile App. If you are taking PPI drugs, I recommend talking to your doctor about tapering off these drugs over a period of two to three weeks. I do not recommend people with SIBO undergo antibiotic treatments without first trying to control the overgrowth of bacteria by the two approaches described above. Based on the rational presented in this article, controlling SIBO and GERD by general or selective carbohydrate restriction should dramatically improve the symptoms and severity of asthma, but only clinical testing can provide the proof. References 1. Sontag SJ, O’Connell S, Khandelwal S, Miller T, Nemchausky B, Schnell TG, Serlovsky R. Most asthmatics have gastroesophageal reflux with or without bronchodilator therapy. Gastroenterology. 1990 Sep;99(3):613-20. A Bediwy, M Elkholy, M Al-Biltagi, H Amer, and E Farid. Induced Sputum Substance P in Children with Difficult-to-Treat Bronchial Asthma and Gastroesophageal Reflux: Effect of Esomeprazole Therapy. Int J Pediatr. 2011; 2011: 967460. 2. Leggett JJ, Johnston BT, Mills M, Gamble J, Heaney LG. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in difficult asthma: relationship to asthma outcome. Chest. 2005 Apr;127(4):1227-31. 3. Parsons JP, Mastronarde JG. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010 Jan;16(1):60-3. 4. Dener IA, Demirci C. Explosion during diathermy gastrotomy in a patient with carcinoma of the antrum. Int J Clin Pract. 2003 Oct; 57(8):737-8. 5. Bigard M-A, Gaucher P, Lassalle C. Fatal colonic explosion during colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterology 1979; 77: 1307-1310. 6. Yancy WS Jr, Provenzale D, Westman EC. Improvement of gastroesophageal reflux disease after initiation of a low-carbohydrate diet: five brief cased reports. Altern Ther health med. 2001. Nov-Dec; 7(6):120,116-119. 7. Austin GL, Thiny MT , Westman EC, Yancy WS Jr, Shaheen NJ . A very low-carbohydrate diet improves gastroesophageal reflux and its symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2006 Aug;51(8):1307-12. 8. Eades M. Protein Power. 1996 Bantam Books. 9. Pennathur A, Tran A, Cioppi M, Fayad J, Sieren GL, Little AG. Erythromycin strengthens the defective lower esophageal sphincter in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Surg. 1994 Jan;167(1):169-173. 10. Pehl C, Pfeiffer A, Wendl B, Stellwag B, Kaess H. Effect of erythromycin on postprandial gastroesophageal reflux in reflux esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 1997 Jan;10(1):34-37. 11. Piche T, des Varannes SB, Sacher-Huvelin S, Holst JJ, Cuber JC, Galmiche JP. Colonic fermentation influences lower esophageal sphincter function in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2003 Apr;124(4):894-902. 12. Dodds WJ, Dent J, Hogan WK, Helm JF, Hauser R, Patel GK, Egide MS, Mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with reflux esophagitis. N. Engl J Med. 1982. Dec 16;307(25):1547-52. 13. Lin M, Triadafilopoulos G. Belching: dyspepsia or gastroesophageal reflux disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Oct;98(10):2139-45. 14. Ledson MJ, Tran J, Walshaw MJ. Prevalence and mechanisms of gastro-oesophageal reflux in adult cystic fibrosis patients. J R Soc Med. 1998 Jan;91(1):7-9. 15. Vic P, Tassin E, Turck D, Gottrand F, Launay V, Farriaux JP. Frequency of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and in young children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Pediatr. 1995 Aug;2(8):742-6. 16. Fridge JL, Conrad C, Gerson L, Castillo RO, Cox K. Risk factors for small bowel bacterial overgrowth in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007 Feb;44(2):212-8. 17. Nastaskin I, Mehdikhani E, Conklin J, Park S, Pimentel M. Studying the overlap between IBS and GERD: a systematic review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2006. Dec;51(12):2113-20. 18. Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3503-6. 19. Austin GL, Dalton CB, Hu Y, Morris CB, Hankins J, Weinland SR, Westman EC, Yancy WS Jr, Drossman DA. A very low-carbohydrate diet improves symptoms and quality of life in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Jun;7(6):706-708. 20. Majewski M, Reddymasu SC, Sostarich S, Foran P, McCallum RW. Efficacy of rifaximin, a non absorbed oral antibiotic, in the treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Am J Med Sci. 2007 May;333(5):266-70. 21. Pimentel M. Review of rifaximin as treatment for SIBO and IBS. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009 Mar;18(3):349-58. 22. Yang J, Lee HR, Low K, Chatterjee S, Pimentel M. Rifaximin versus other antibiotics in the primary treatment and retreatment of bacterial overgrowth in IBS. Dig Dis Sci. 2008 Jan;53(1):169-74. 23. Lombardo L, Foti M, Ruggia O, Chiecchio A. Increased incidence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth during proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Jun;8(6):504-8. 24. Hagen J, Deitel M, Khanna RK, Ilves R. Gastroesophageal reflux in the massively obese. Int. Surg. 1987 Jan-Mar;72(1):1-3. 25. Fisher BL, Pennathur A, Mutnick JL, Little AG. Obesity correlates with gastroesophageal reflux. Dig Dis Sci. 1999 Nov;44(11):2290-4. 26. Austin GL, Thiny MT , Westman EC, Yancy WS Jr, Shaheen NJ . A very low-carbohydrate diet improves gastroesophageal reflux and its symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2006 Aug;51(8):1307-12. 27. Vakil N, Shaw M, Kirby R. Clinical effectiveness of laparoscopic fundoplication in a US community. Am J Med. 2003 Jan;114(1):1-5. 28. Klaus A, Hinder RA, DeVault KR, Achem SR. Bowel dysfunction after laparoscopic anti reflux surgery: incidence, severity, and clinical course. Am J Med. 2003 Jan;114(1):6-9. 29. Beldi G, Gláttli A. Long-term gastrointestinal symptoms after laparoscopic nissen fundoplication. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002 Oct;12(5):316-9. 30. Hirschowitz BI, Worthington J, Mohnen J. Vitamin B12 deficiency in hypersecretors during long-term acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008. Jun 1;27(11):1110-21. 31. Marcuard SP, Albernaz L, Khazanie PG. Omeprazole therapy causes malabsorption of cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12). Ann Intern Med. 1994 Feb 1;120(3):211-5. 32. Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC . Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006 Dec 27;296(24):2947-53. 33. Targownik LE , Lix LM , Metge CJ , Prior HJ , Leung S , Leslie WD . Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008 Aug 12;179(4):319-26. 34. Patel TA, Abraham P, Ashar VJ, Bhatia SJ, Anklesaria PS. Gastric bacterial overgrowth accompanies profound acid suppression. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1995 Oct;14(4):134-6. 35. Fried M, Siegrist H, Frei R, Froehlich F, Duroux P, Thorens J, Blum A, Bille J, Gonvers JJ, Gyr C. Duodenal bacterial overgrowth during treatment in outpatients with omeprazole. Gut 1994; 35:23-26. 36. Shindo K, Machida M, Fukumura M, Koide K, Yamazaki R. Omeprazole induces altered bile acid metabolism. Gut. 1998 Feb;42(2):266-71. 37. Theisen J, Nehra D, Citron D, Johansson J, Hagen JA, Crookes PF, DeMeester SR, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR, Peters JH. Suppression of gastric acid secretion in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease results in gastric bacterial overgrowth and deconjugation of bile acids. J Gastrointest. Surg. 2000 Jan-Feb;4(1):50-4. 38. Lombardo L, Foti M, Ruggia O, Chiecchio A. Increased incidence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth during Proton Pump Inhibitor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Jun;8(6):504-8. 39. Fossmark R , Johnsen G , Johanessen E , Waldum HL . Rebound acid hypersecretion after long-term inhibition of gastric acid secretion. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Jan 15;21(2):149-54. 40. Reimer C, Søndergaard B, Hilsted L, Bytzer P. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology. 2009 Jul;137(1):80-7. 41. Laheij RJ , Sturkenboom MC , Hassing RJ , Dieleman J , Stricker BH , Jansen JB . Risk of community-acquired pneumonia and use of gastric acid-suppressive drugs. JAMA. 2004 Oct 27;292(16):1955-60. 42. Canani RB, Cirillo P, Roggero P, Romano C, Malamisura B, Terrin G, et al. Therapy with gastric acidity inhibitors increases the risk of acute gastroenteritis and community-acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatrics 2006;117:e817-20. 43. Mertens V, Blondeau K, Pauwels A, Farre R, Vanaudenaerde B, Vos R, Verleden G, Van Raemdonck DE, Dupont LJ, Sifrim D. Azithromycin reduces gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration in lung transplant recipients. Dig Dis Sci. 2009 May;54(5):972-9. 44. Littner MR, Leung FW, Ballard ED 2nd, Huang B, Samra NK Effects of 24 weeks of therapy on asthma symptoms, exacerbations, quality of life, and pulmonary function in adult asthmatic patients with acid reflux symptoms. Chest. 2005 Sep;128(3):1128-35. 45. Mastronarde JG, Anthonisen NR, Castro M, Holbrook JT, Leone FT, Teague WG, Wise RA. Efficacy of esomeprazole for treatment of poorly controlled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009 Apr 9;360(15):1487-99. 46. Johnston SL, Blasi F, Black PN, Martin RJ, Farrell DJ, Nieman RB; TELICAST Investigators. The effect of telithromycin in acute exacerbations of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006 Apr 13;354(15):1589-600. What should reflux sufferers and asthmatics do?

What about a digestive enzyme to process these extra carbs? I know amylase is produced through saliva but is destoyed by stomach acid if it reaches the stomach. Is there another enzyme that can survive in the stomach and beyond to digest these excess carbs?

Also I take Dexilant 60mg (PPI) so I don’t have near as much stomach acid as the average person.

Thanks,

Ty

Hi Ty,

Sorry about approving your comment late, but I was swamped with spam on this blog. Hopefully, my new spam plug-in will help with that in the future. You are correct that supplementing digestive enzymes could help. Lactase enzyme for lactose intolerant individuals and amylase enzyme to help with starch digestion. Supplements made by reputable companies that have defined potency, expiration dates and are properly stored and have a protective coating to protect against stomach acid are preferable. My first recommendation would be to avoid the most difficult-to-digest carbs first – The Fast Tract Diet approach which I write about in my soon-to-be released book by the same name.

Fascinating. I have been on PPI’s since 1998, when they successfully reversed a reflux-induced granuloma on the vocal chord. However, 18 months ago I began experiencing shortness of breath and severe bloating and belching. Several doctors later, I have finally been diagnosed with SIBO, though current treatment with Xifaxan does not seem to be relieving symptoms. I wonder if in addition to causing extra pressure from fermentation and thus creating reflux, the bacteria–unsuppressed by acid–actually also create additional acid as they feed and ferment, acid that would not normally be present.

Hi Derek,

I appreciate your comment. Ten months after posting this article, you are the first to post a legitimate comment amid hundreds of spam comments.

I am glad you finally have a diagnosis you can act on, though I am not an advocate of antibiotics for this condition. Because of the diverse collection of bacteria involved, broad spectrum antibiotics, such as xifaxan, are required. But these antibiotics may not kill all the strains involved (unsuccessful treatment) or they kill off so many gut microbes, including healthy bacteria in both the small and large intestine, that bad bacteria such as C. diff. grow back and create even worse problems.

You are certainly right in your thinking that overgrowth of bacteria will produce more acid, but this acid is not nearly as concentrated as stomach acid. The key, in my opinion, is not limiting acid, but keeping acid from refluxing into the esophagus, sinuses and lungs.

Have you tried cutting carbs to treat the condition? Also, focus on easier to digest carbs if you must indulge and avoid pasta and any breads other than a single slice of white bread. Also, chew starchy foods well to allow saliva amylase more time to act on the starch.

I am just finishing a new book called Fast Tract Digestion for GERD (the first in a book series) that you might be interested in. The book, which comes out as an Amazon ebook around summer’s end, provides lots of new research on this topic and recommends a new type of diet to minimize malabsorption that leads to SIBO, GERD and related symptoms and conditions.

Thank you for writing this article. I have been suffering from reflux and now in the last year asthma and after several tests was told I did not have relux. My GP, a great doc, told me he believed I did have reflux but my acid levels were low on the test. The problem was my GI, GP, ENT and Pulmonary specialists didn’t have any solutions. I’ve always suspected SIBO and I am now going on a strict diet. Thank YOU! Also, wonder if you find any connection with this and Candida overgrowth?

Hi Joseph,

Thanks for writing. I would be interested in hearing about your results. My understanding is that Candida is more common after antibiotic treatment or immunosuppression. Like bacteria, Candida should respond positively to reduced carbohydrate malabsorption.

A very interesting article. I have recently noticed a possible link between eating carbohydrates and how bad my asthma is but thought I was clutching at straws. Now, having read your thoughts I am now going to investigate further and experiment with my diet.

Thank you for writing this.

Hi Sandra,

Thanks for your comment. I would be interested in hearing about your symptoms if you cut some carbs. I have a new diet for GERD. The book is called Fast Tract Digestion for GERD. the book should be released in the next month or so.

Thank you for your research. I’ve had asthma for 45 years and GERD for 20. I’ve been on Nexium for over 10 years. My daughter has Celiac Disease. I’ve tried a gluten free diet which helps my GERD symptoms probably because it forces me to cut carbs. I’m going to buy your book and try a low carb diet. Thanks again!

Thank you for this informative article. My quality of life is so negatively impacted by my severe non-stopping GERD systems. I am so desperately looking for any solutions. I would like to purchase the Fast Track Digestion book. Do you have a paperback version? Thank you again.

Fast Tract Digestion Heartburn is heading to the printers in the next couple of weeks. Look for it towards the end of September on Amazon. For now, it’s available on Kindle. Good luck WC. I know how bad this condition feels as I suffered for many years with GERD.

Update: Fast Tract Digestion Heartburn, paperback is now available. Go to the “buy books” tab on the home page.

Many years ago, I noticed that a prior warning of an impending chest infection was an attack of GERD. I put it down to a change in pressure in the lungs forcing acid back up, which would also mimic increased pressure in the gut forcing acid back up. Alternately, the relative changes in pressure either side of the diaphragm affect the stomach valve, holding it open.

Since discovering I was coeliac, and avoiding gluten, I have had incredibly few chest infections – down from 6-8 per year, to 1 every 2 years – and no GERD.

Great news Jenny. Your response to going gluten free (which also cuts down on difficult to digest carbs in general) makes perfect sense. The pressure from below is likely the most important factor. The only difference may be smoking because taking drags may create enough suction to help force open the LES.

A rider to the above: 2 years ago, I had a very severe ear infection and was put on IV Augmentin and Nexium. Within 2 days, I had huge bloating – 0-6mths pregnancy style bloating in 40mins and growing! Enough to seriously affect breathing. A longer after-effect was that my acid levels did NOT rebound, and I had to take extra acid for 9 mths.

2 years on, I still have some bloating and have finally gone onto a SIBO diet, plus extra additional pro-biotics. I say extra, because as a coeliac, I normally take a maintenance dose anyway.

I have read Elaine Gottschall’s book, but may well read yours as well. I will be interested to read more about the carbohydrate problem.

Thanks for sharing this info Jenny. Both the antibiotic and Nexium would be expected to exacerbate the underlying problem. Sounds like you’re going in a positive direction now. Just keep in mind that amylose starch (not amylopectin) is the enemy (Breaking the Vicious Cycle has a typo reversing these). The book also utilizes (and does not limit) fructose containing foods like honey which can be a huge problem for many people with gut issues.

I stumbled across this article in one of my many searches to solutions for the many physiological issues I suffer from. I am 32, have been asthmatic since 1.5 yrs old, suffered from intense GERD since the age of ~20, suffered from extremely painful nighttime episodes of acid shooting into my lungs occasionally at nighttime since the age of ~29, and also suffer from various other symptoms such as fatigue.

In the past few years I have made some significant improvements. I no longer eat gluten/wheat or dairy. I first stopped wheat because every time I ate it I had severe fatigue…I don’t believe I am celiac and tests have backed this up. Then to my surprise I discovered eliminating dairy went a long way towards decreasing nighttime episodes of reflux into the lungs. In terms of my asthma, I have observed over the past 5 years or so that using an albuterol inhaler leads to dependence in my case i.e. immediate relief followed by worse than usual breathing difficulties that can be relieved via albuterol but lead to cycle of increased symptoms and dependence. My asthma is induced by things I am allergic to such as animal dander like dogs and especially cats, and exercise. I keep the inhaler around for absolute emergencies, for instance when I am sick I am much more susceptible to breathing difficulties, however on a day to day basis controlling my general health basically eliminates asthma symptoms. Diet definitely is part of this, as is weight, and another huge part is exercise. Virtually every time I jog/run I experience some degree of airway constriction however I have found I can push through this and it dissipates. The regular exercise makes the symptoms that do appear during exercise much lighter and, improves breathing during other times to the degree that again, the only time I might ever feel like using an inhaler is if I am seriously sick where fluids/mucus have infiltrated and aggravated the lungs.

Your article is very interesting to me because it appears to possibly make a lot of sense and as you also noted, the current accepted theories about GERD make little sense at least in terms of my own case. I have had 2 endoscopies, the first revealed a fair amount of damage to my esophagus and the second, after some time on PPI’s, revealed significant healing of the damage. I have gone on and off PPI’s for years however, I try not to stay on for too extended a period of time because despite what the doctors say I don’t believe they are safe because such a claim just defies common sense. So the funny thing is, between the first and second endoscopy, I had started smoking…please don’t ask why, it was stupid and I stopped…just a stressful time and…well anyways there is no excuse. Anyways, based on my own observations of my own body and degrees of pain experienced etc. I don’t think the improvement between endoscopies came from the PPI’s (which I had already been taking on and off anyhow) but rather indirectly from the smoking. During this time I had an alleviation of GERD symptoms…despite the claims that smoking and caffeine are culprits in GERD…and if I had to form an educated guess I would say it was almost surely primarly due to reduced food intake as I definitely was eating significantly less when smoking and experiencing much less GERD. Definitely the PPI’s were part of the improvement but as stated I had already been on and off these, so the combination of PPI’s and reduced caloric intake had a much bigger impact than PPI alone.

Based on the results of the endoscopy the doc claimed I had a very minor hiatal hernia. Now, even before any endocopy had been performed, I thought the whole idea of this all being attributed to a hiatal hernia sounded really suspicious. A few thoughts were a) there is a very large % of people experiencing GERD and it is attributed to a structural anomaly like a hernia – just doesn’t sound right, and b) if it is all due to hernia it must be a bad hernia because my GERD was very serious and yet I can hang upside down ok and stuff doesn’t just come spewing out of my stomach into my esophagus or mouth – this also doesn’t make much sense to me. So anyways the claim by the doc that there was only a very minor hernia was not surprising. So, here I am with very serious GERD and only a slight (supposed) hiatal hernia…hmmm seems reasonable to conclude there are additional issues or this (supposed) hernia was not the issue at all. I start rattling off questions to the doc which at first he attempts to humor and then funny enough I think he wanted to escape me as he was doing a very poor job of answering my questions. I can tell within minutes that while this guy has some training and fundamental knowledge about the human body that I lack since I am complete layman, just like most of the other docs I have met with he is not a real sharp guy and just parrots off whatever he has learned as if it is all facts. He did not want to discuss anything besides keeping with the PPI drugs and made claims about how safe they were when questioned about it. His answers about the safety of the PPI drugs were pure drivel, and I am not saying I know they are not safe for a fact, but he surely did not demonstrate it even to a small degree.

Last thing is, I remember when I first discovered wheat as a culprit, I was actually restricting carb intake and trying to follow a somewhat paleo diet. I forget why I was restricting carbs, I think it was just a general idea of trying to follow a diet our bodies were better equipped for, I had not at that time made any connection between malabsorbed carbs and GERD. What I do remember though, is I felt great during that time (little less than a month), and while I continued with the wheat elimination because I had made that connection, I did not continue entirely with carb restriction/paleo type diet because I had not made the connection.

In conclusion, I find your article and analysis compelling and thoughtful and I have not come across a more convincing explanation. The voters for Google also apparently agree as this article is performing very well in search. I cannot say I am a believer, but I can say you present the evidence convincingly enough I will be changing my diet significantly and observing the results. I hope that I can return and report excellent results. Thank you :)

Hi Jason,

Thanks for taking the time to share you enlightening experiences and learnings on GERD and asthma. While it make sense to me that people with hiatal hernia will suffer more symptoms due to the increased intr-abdominal pressure associated with this condition, I agree there is much more to it. The real driver is gas-producing bacteria that feed on malabsorbed carbs. While giving up wheat and dairy (low lactose diary such as heavy and light cream and fermented diary is OK) is a big step in the right direction, these dietary changes are not enough for full recovery. I hope you try the Fast Tract diet and report back on your results for your GERD and asthma symptoms.

Norm, thanks I did buy the book yesterday and read most of it already. I will be implementing it soon and will make it a point to report back. Excellent book btw, there was some really helpful information in there I did not expect, and if it does turn out to essentially ‘cure’ things it is just beyond awesome. Now you have me thinking about gases and such every time I go to eat/drink something.

Glad to hear it Jason. I look forward to hearing about your progress.

I have CF and the past few years I have been experiencing horrible stomach issues. Loss of appetite, very acidy stomach and stomach upset etc. I am convinced that taking so many antibiotics in my lifetime have severely screwed up my stomach and all the docs want to do is put me on more prescription crap that I really don’t want. I usually try and use supplements to take care of things but I am having a hard time with this one. I am convinced that I have GERD now after reading this article. I take acidophilus daily and that helps with the build up of candidiasis but hasn’t seem to fully help with my stomach issues. Do you have any advice for me such as a change in diet or some supplements that I can take to help? This GERD has really affected my lungs and overall life so I really hope you can help in some way before I take the pharmaceutical route. Thank you.

Hi Alissa,

Have you been diagnosed with SIBO and do you take enzyme supplements as well? I would expect that the Fast Tract Diet would complement the enzyme supplements to improve your condition.

No I have not been officially diagnosed with SIBO. Yes I take enzyme supplements as well. Looks like I will have to look into the fast tract diet.

Norm,

I think you have overlooked some pharmacology which explains the mechanism of action for erythromycin and azithromycin in GERD. You asked, “how can an antibiotic tighten these muscles?” in reference to the LES. Both drugs are motilin agonists. Motilin agonism stimulates cholinergic pathways, ultimately producing contractions of GI tract smooth muscles. Motilin is best known for increasing intestinal peristalsis, and that alone would be expected to reduce GERD by combating SIBO, however it also tightens up the lower esophageal sphincter at the same time.

Additionally, the doses of erythromycin prescribed when it used as a prokinetic are small (typically 50mg at bedtime) — far lower than effective antibiotic doses.

Hi Sean,

If I have overlooked something, I am open to getting to the bottom of it. I would be interested in the evidence that erythromycin is a motilin agonist, but more importantly, that it can actually increase preristalsis and reduce GERD by a mechanism other than the one I have proposed – by inhibiting bacterial growth and gas. Are you aware of this evidence? Maybe I am missing something, but I have not been able to find it.

Norm,

Here is some evidence that erythromycin is a motilin agonist and increases LES pressure. Upon further review, it seems to accelerate only gastric transit, not the small intestine and colon. Still, the evidence that erythromycin significantly increases LES pressure supports the original, non-antibiotic explanations for its efficacy in GERD.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8342132

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8313822

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8311129

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11151866

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19937173

Thanks for pulling these together Shawn. I have read some of these but will take a closer look at all of them. Are you clear that I am suggesting the apparent “strengthening of the LES” following erythromycin administration is actually the reduction of intragastric pressure from the inhibition of gut microbes? In that light, you would expect the same findings, but I am offering a different interpretation of the underlying cause of the effect.

I do understand your hypothesis. However, this stimulation of the LES by erythromycin, causing the muscle to contract more forcefully, appears to be a straightforward neurochemical cause/effect. Please review my second pubmed link, where the effect of erythromycin on the LES is dependent on acetylcholine and can be completely blocked by an anticholinergic agent (atropine).

Also, the fourth study confirms erythromycin acts by releasing acetylcholine and suggests 5-HT3 receptors are also involved:

“CONCLUSIONS:

Erythromycin exerts its prokinetic action on the lower esophagus by stimulating cholinergic pathways. This action includes not only an increase in LES pressure, but significant increases in the amplitude and duration of esophageal peristalsis, as well. 5-HT3 receptors are also involved in this process.”

These studies agree with the clinical use of erythromycin as a prokinetic at ineffective antibiotic doses (50 mg) as well as studies which produce LES stimulation by erythromycin immediately after it is administered via intravenous route (no contact with gut flora and no time to produce antibiotic effect).

Hey Shawn,

Thanks for taking the time to challenge this idea. I will send for the second paper to read it in full. I am interested in better understanding the effect of atropine because I’m a little skeptical of the interpretation of it’s effects on the erythromycin activity. Atropine may just overpower any affect on the LES including one driven by gas producing bacteria.

One theory proposes that Reflux and LES “relaxation” occurs in response to a well documented increased in intragrastric pressure (which I propose is caused by gas produced by gut bacterial overgrowth). It turns out that atropine actually blocks that response. (https://gut.bmj.com/content/41/3/285.full). In other words, regardless of a direct effect of erythomycin on the LES or indirect effect via antimicrobial action, atropine may abolish it. Atropine has other unusual properties including:

– Independently reduces basal LES pressure, frequency of spontaneous reflux and rate of transient LES relaxations (https://gut.bmj.com/content/43/1/12.full). Which could be from it’s affect on intragastric pressure – We don’t know.

– Acts synergistically with some antibiotics against bacteria (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10188813).

“These studies agree with the clinical use of erythromycin as a prokinetic at ineffective antibiotic doses (50 mg)”

NR: The use in this capacity came from the original study on it’s proposed effect on the LES. Where is the data that it’s effective in either capacity at this reduced concentration? It may exist, but I haven’t seen it.

“as well as studies which produce LES stimulation by erythromycin immediately after it is administered via intravenous route (no contact with gut flora and no time to produce antibiotic effect)”

NR: Where is the data showing this effect is immediate? I will double check this myself as well.

One experiment that could resolve the issue is to do the erythomycin challenge after a complete colon cleanse. Just a thought.

Norm,

That is some interesting information regarding atropine. About the use of erythromycin at 50 mg, it was shown to delay the recurrence of SIBO after antibiotic treatment at this low dose (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20574504). In that study, it performed worse than rival prokinetic tegaserod, but significantly better than placebo. I think you are familiar with Dr. Allison Siebecker; she also claims some success with 50 mg erythromycin nightly in her SIBO practice.

There are several studies documenting increased LES pressure after I.V. erythromycin. In the first one I was able to access (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11413601), the increased LES pressure is documented just 15 minutes after IV infusion of the drug. It is possible that some hours later, enough erythromycin or active metabolites would be excreted via the liver to affect the gut flora — however, I think its extremely unlikely this could occur within 15 minutes.

Erythromycin’s effect on the esophagus is not limited to strengthening of the LES. In this study (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11413601) they documented increases in various measures of peristalsis in GERD patients after IV infusion.

I’m a huge fan of yours and I hope this doesn’t come across as nitpicking. I’ve read both of the Fast Tract Digestion books and seen significant improvements in GERD and IBS-C symptoms by following your suggestions. Recently, I was enticed by outspoken advocates of resistant starch to experiment with their approach to digestive health: soil-based probiotics combined with various food and supplement sources of resistant starch. The results were disastrous. I developed chest pain and cardiac symptoms so severe I ended up in the ER thinking I was having a heart attack. Turns out it was nothing more than my longtime GERD, turbocharged by RS. That experience rekindled my interest in your work, and I’m improving since trading the raw potato starch for jasmine rice and well-cooked pontiac potatoes.

Shawn,

I find it difficult to be swayed very much by the study you cite on low dose erythromycin due the the amount of uncertainty in the data. For instance the results of low dose erythromycin are: “Prevention using erythromycin (n=42) demonstrated 138.5±132.2 symptom-free days.” So it could be as few as 6 days or as many as 270 days. I would imagine the amount of variability in the durability of the initial response to antibiotic therapy is quite large to begin with. And the study does not conclude that erythromycin is effective at preventing recurrence, but rather “Tegaserod significantly prevents the recurrence of IBS symptoms after antibiotic treatment compared to erythromycin or no prevention.” As for Dr. Siebeckers’s (big fan of hers by the way) experience, I find it difficult to comment as I don’t know what other simultaneous interventions she may have been recommending.

I’ll withhold comment on this paper (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11413601) until I read it. I have ordered it. Do you happen to have the full length paper showing that the effect occurs in 15 minutes? By the way Erythromycin is rapidly disseminated throughout the body based on it’s pharmacokinetic profile (https://aac.asm.org/content/56/2/1059/F1.expansion.html). Is there reason to believe it reaches potential neurological targets more quickly than it reaches bacteria in the gut?

Lastly, thanks for your comment on nitpicking, but no need for concern. Like you, I just want to understand what’s really going on. Debating the merits of new ideas is key to that process. Also, glad you are benefiting from the underlying idea that gut bacteria excessively fermenting hard-to-digest carbs drives acid reflux.

I do have the full length paper on that IV erythromycin and I’d be happy to e-mail it to you (I don’t have your address though). Erythromycin is metabolized by the liver so I would expect metabolites of erythromycin and a smaller amount of unchanged erythromycin to be excreted into the GI tract via bile at a rate dependent on its elimination half-life of 1.5-2 hours.

In that study LES pressure more than doubled from 17 mmHg to 41 mmHg only 15 minutes after the IV infusion. I just think it is a stretch to attribute that effect to killing of gut flora when other studies have mapped out every step of a neurochemical mechanism of action, beginning with agonism of motilin receptors. It seems all macrolide antibiotics share that property. Here is a study which compares azithromycin with erythromycin and confirms both are motilin agonists: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23190027

Erythromycin, like most antibiotics, penetrates tissue throughout the body rapidly either from the GI tract when given orally or from the bloodstream to the tissue when given IV. I’m not sure why you believe it needs to enter via bile/liver. There’s every reason to believe in my view that rapid penetration into the GI tract occurs, especially given the amazing surface area between the intestinal villi and the blood stream.

As soon as the erythromycin reaches the bacteria, all protein synthesis is shut down. That means no more metabolism and no more gas. I am not debating that the “As measured LES pressure more than doubled”, I am just proposing that this effect is due to the inhibition of gut microbes, loss of the gas microbes produce and a resulting loss of intragastric pressure. This seems very plausible to me. The fact that other non-antibiotic substances can have a “motilin-like” effect doesn’t prove anything about erythromycin to me.

The intestinal lumen is external to the body and its tissues. In order for significant quantities of antibiotic to accumulate there, when an antibiotic is administered by IV, it must be eliminated by the hepatic route. There is miminal exposure of gut flora to IV antibiotics that are eliminated renally.

I think you will agree that point is tangential after you review the study below. The antibiotic properties of erythromycin are generally undesirable for its use as a prokinetic. Derivatives of erythromycin, which retain its motilin agonism but without antibiotic activity, exist and have been researched as drug candidates. What follows is evidence in an animal model that the effects of macrolide drugs on lower esophageal sphincters have absolutely nothing to do with antibiotic activity:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8119532

Gastroenterology. 1994 Mar;106(3):624-8.

Effects of LY267108, an erythromycin analogue derivative, on lower esophageal sphincter function in the cat.

Greenwood B1, Dieckman D, Kirst HA, Gidda JS.

Abstract

BACKGROUND/AIMS:

Erythromycin (EM-A) and some of its analogues stimulate gastrointestinal smooth muscle contractions. Because gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in humans is in part caused by a reduction in lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure, the aim of this study was to investigate the effect of LY267108 (an EM-A analogue with no significant antimicrobial activity) on LES function.

METHODS:

In ketamine-anesthetized cats, LES pressure was recorded using a Dent sleeve.

RESULTS:

In cats, LY267108 increased LES pressure, as did motilin and EM-A. Neither LY267108, EM-A, nor motilin altered LES relaxation in response to a swallow. LY267108 increased LES pressure in cats in which the basal LES pressure was lowered experimentally by perfusing the distal esophagus with HCl (0.1 N for 3 days) or following isoproterenol (3.0 micrograms/kg intravenously). In summary, LY267108 increases LES pressure in normal cats, did not affect the relaxation of the LES in response to a swallow, and increases LES pressure in animals with an experimentally induced decrease in LES pressure.

CONCLUSIONS:

The results suggest that LY267108 may be useful in treating GERD because of its ability to increase LES pressure and thus present a barrier for gastroesophageal reflux.

I found another study I believe is clincher: a non-antibiotic motilin agonist, amotilin, produces similar increases in LES pressure (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19997977).

Definitely more complex than I imagined Shawn. Thanks for providing the information. I am going back to read some of the underlying papers, for instance the original work on Erythromycin being designated as a “motilin agonist”. Of course, what would really sway me is evidence that concentrations reaching the small intestine are too low or too slow to inhibit the growth of bacteria. As you mentioned erythromycin is discarded via the bile (less than 5% removed through urine). Where does bile go? Into the small intestine. You mentioned “There is miminal exposure of gut flora to IV antibiotics”. While that might be true for feces where most microbes are, is there evidence that erythromycin does not accumulate in the small intestine lunen? Given the tremendous surface area between blood vessels and villi surface, I can’t imagine there is no erythromycin crossing over here.

I have no problem accepting this idea is not valid if the evidence proves it. Just want to be sure.

Hi Norm, thanks very much for this article. My friend and I have been struggling with LPR/GERD for about 15 years and have actually lost most of our voices due to the burning feeling it causes. Bloating and gas were the first symptoms to appear so those parts in your article really rang true.

However restricting intake of carbs and even going on a strictly ketogenic diet for a year has not helped.

Would you mind if I asked what other options there are? Personally I’ve had a Nissen Fundoplication, seen a neverending list of ENTs and Gastros, have been on and off PPI’s for a decade and done most of the standard and alternate treatments. I’m really quite desperate to get my voice back and would appreciate any ‘pointers’ in the right direction.

Hi I am hoping you can help me, my son is 10 months old and through muscle testing has been diagnosed with SIBO, and also has multiple food allergies and intolerances. He is breastfeed (I exclude the reacting foods) and eats a very paleo diet. He has terrible trapped burps and struggles to sleep until they are all out, it could take 6-8 burps before he relaxes, the first 2-3 are easy the balance are hard to help him get out. Do you have any ideas or recommendations on how I can help him?